Investigation the effect of cigarette smoking on the FKBP6 and XRCC1 genes associated with male fertility

Cigarette smoking, infertility and genes

Authors

Abstract

Aim Tobacco use is growing in all countries and is one of the greatest threats to current and future global health. The negative effect of tobacco use on infertility has been examined in numerous studies. By examining the FKBP6 and XRCC1 genes, the research seeks to evaluate the contribution of polymorphisms in these genes to the risk of infertility in smokers and investigate the correlation between smoking polymorphisms and infertility, especially in Saudi Arabia, where such information is currently insufficient.

Materials and Methods We included 25 smokers, 25 infertile men, and 25 age-, gender-, and ethnicity-matched controls in our study. We tested the hypothesis by analyzing the genotypes for two single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs3750075) in the FKBP6 and (rs25487) in the XRCC1. Chemiluminescent immunoassay technology assessed whether the two SNPs contribute to circulating hormones.

Results The results indicate that smoking does not significantly affect the Fkbp6 (rs3750075) gene. Every single sample was normal (C/C). In contrast, there were changes in XRCC1 (rs25487) between groups, but compared to C/C or C/T, there was less T/T, which is normal, between groups.

Discussion Our results suggest that genetic polymorphisms in the XRCC1 gene may explain the risk of the influence of smoking on infertility.

Keywords

Introduction

Tobacco use and its complications cause more than 8 million deaths annually worldwide. Although global tobacco use has steadily decreased, the number of smokers has remained constant due to population growth. Nevertheless, the efforts to reduce tobacco demand and related mortality and illness are falling short of the global and national promises to cut tobacco use by 80% by 2025 [1]. In Saudi Arabia, the overall prevalence of tobacco use is 26.3% [2].

Smoking adversely affects male sex and reproductive hormones, which are significantly lower in male smokers compared to nonsmokers [2]. Qutub and others reported that a study conducted on infertile males attending infertility clinics in Jeddah showed a negative correlation between smoking tobacco and the production of testosterone hormones related to reproduction [3]. Also, smoke affects the secretion of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland [4]. These disruptions can significantly impact testosterone synthesis and spermatogenesis.

Heredity plays a role in smoking behavior [5]. Certain gene variants may be useful biomarkers for identifying individuals susceptible to DNA damage. Oxidative stress and the production of ROS are some of the harmful effects of cigarette smoking. However, ROS-induced polymorphism damages the sperm genome, increasing the risk of infertility [6]. The XRCC1, which has 17 exons and 16 introns and is found on 19q13.2, encodes the XRCC1 protein [7]. A study suggests that the gene may be involved in repairing DNA damage during spermatogenesis [8]. However, there are no studies investigating the correlation between XRCC1 with smoking and infertility. FKBP6 (FK506- binding protein 6) is a 327 amino acid protein that plays a role in protein folding by accelerating the process [9]. Furthermore, pathogenic mutations of the FKBP6 are essential for azoospermia [10].

By examining the FKBP6 and XRCC1 genes, the research seeks to evaluate the contribution of polymorphisms of the FKBP6 and XRCC1 genes to the risk of smoking and infertility and investigate the correlation between the polymorphisms of smoking and infertility, especially within the context of Saudi Arabia, where such information is currently insufficient.

Materials and Methods

Subject

A total of 75 men between the ages of 19 and 60 were selected and divided into three groups: Control (C) group (n=25), which are non-smokers and have no problem with fertility; the Infertile (Inf) group (n=25), has fertility issues diagnosed by the Health Service Administration Department at King Abdulaziz University and the Health Plus Fertility and Women Health Center in Jeddah, but who are not smokers; and the Smokers (S) group (n=25), which are smokers but don’t have fertility issues. Study subjects provided information on their body mass index, age, medical, nutrition, and smoking history using structured questionnaires [11, 12, 13].

Anthropometric Measurement And Biochemical Analyses

A venous blood sample was taken to a plain test tube to measure the level of the following sexual hormones: testosterone, prolactin, FSH, and LH. Abbott kits were used to analyze hormone samples.

DNA Extraction and FKBP6 and XRCC1 Genotyping

Venous blood samples were obtained into an EDTA tube for DNA extraction using QIAamp® DNA Mini and Blood Mini kits. All DNA sample concentrations were measured using the Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to determine the purity of the samples. The regions of interest within the applied gene (FKBP6 and XRCC1) will be amplified using the polymerase chain reaction technique.

Using the run method described in the Haven® SNP Genotyping Assays user guide, we employed thermocycling conditions in an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlusTM RealTime PCR system to amplify the extracted DNA. A final volume of 10 μl was achieved in each PCR reaction by adding 20 ng of extracted DNA, 5.0 lL TaqMan Master Mix (2×), 0.5 lL primers and probes (20×), and Nuclease-Free Water. PCR products used Applied TaqManTM Genotyper Software to automatically determine genotypes and display data.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was delivered by Python 3.11.4. The hormonal analysis was delivered by Python version 3.8.8.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Date: 2021-03-18, No: 08-CEGMR-Bioeth-2021), Saudi Arabia.

Results

a)Genotype Distributions and Allele Frequencies of the FKBP6 (rs3750075) and XRCC1 (rs25487) SNP

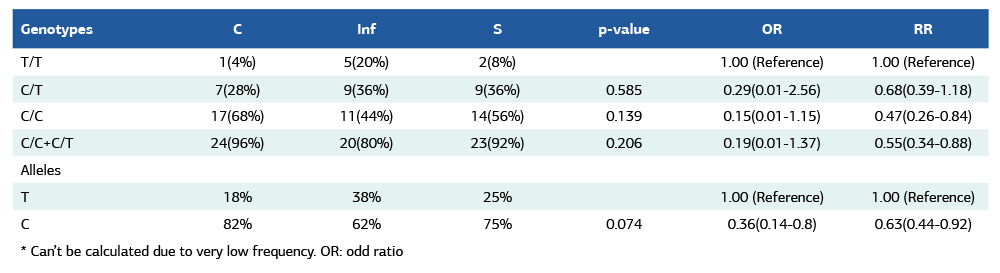

The whole distribution of genotyping for FKBP6 rs3750075 and XRCC1 rs25487 is examined in Table (3), 100% of samples have a normal genotype of C/C for FKBP6 rs3750075, which indicates there is no relationship between smoking and fertility. In contrast, there is some variety of genotyping between groups. Table (1) displays the genotypes and allele frequencies of XRCC1 rs25487 SNP. The C allele at the XRCC1 polymorphism was associated with a higher risk of infertility.

Moreover, it was clear that the majority in the (C) as well as (S) groups are C/C, whereas in the (Inf) group, C/C and C/T are nearly around 40% (11 (44%) and 9 (36%) respectively). The T/T is about 20% in the (Inf) group and 4% and 8% in the (C) and (S) groups, respectively.

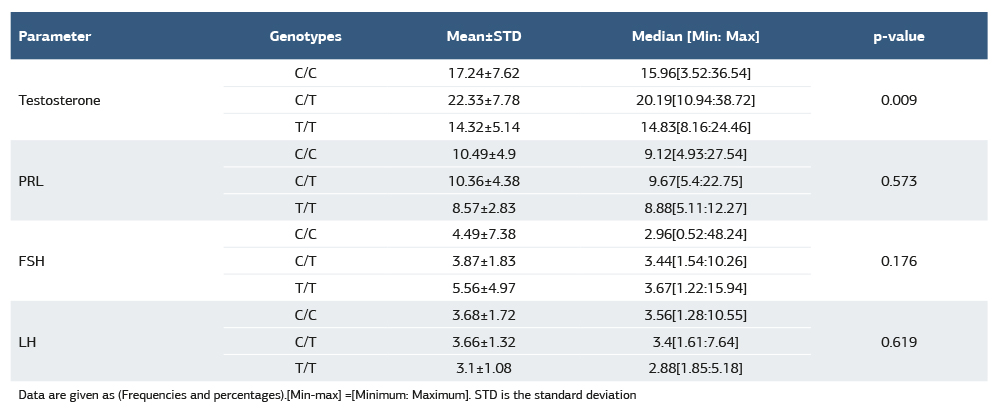

When hormones are compared among different XRCC1 rs25487 types in Table 2, there were no significant differences among the SNP types except the testosterone, which is significantly lower in the T/T group. Moreover, the C/T has significantly higher testosterone than the C/C.

A two-way ANOVA was proposed to check the difference when different groups (C, Inf, and S) were considered along with the SNP types. The interaction effect wasn’t significant in hormones (p-values of interaction: testosterone: 0.638, prolactin: 0.909, FSH: 0.963, LH: 0.908).

Comparing Hormonal Changes Among Different Groups Testosterone

In multiple comparison tests, there was no significant difference between (C) and (Inf) groups. However, (S) had a higher mean (21.1 ± 7.9) than the (C) group (16.3 ± 6.9) and (Inf) group (16.4 ± 6.5).

LH

LH was compared among (Inf) and (S) groups; there was a significant difference (p-value = 0.049). LH showed a rise in the (S) group. Furthermore, most of the subjects in (S) (more than 75%) have LH greater than 2.5 IU/l, whereas only 50% of the (Inf) group are above this value.

FSH

There is a significant difference among groups. Where the control group has lower FSH (2.4 ± 0.8) than other groups (3.4 ± 1.6 and 3.1 ± 1, respectively). Also, more than 50% of subjects in the (S) and (Inf) group have FSH greater than 3 IU/l, whereas the majority of subjects in the (C) group (more than 75%) have FSH lower than this value.

Prolactin

There is a significant difference among the groups. The (inf) group has significantly higher prolactin (10.9 ± 3.8 ng/mL) than other groups (8.7 ± 2.7 ng/mL and 8.7 ± 2.3 ng/mL, respectively). Although the maximum level in the (Inf) group was about 20 ng/dL, this level didn’t exceed 15 ng/dL in other groups. About 25% of the (Inf) group has prolactin greater than 13 ng/dL, whereas most of group (C) and all group (S) are below this value. Furthermore, 50% (Inf) group has prolactin greater than 11 ng/dL, whereas only 25% of other groups are above this limit.

Categorizing Hormones

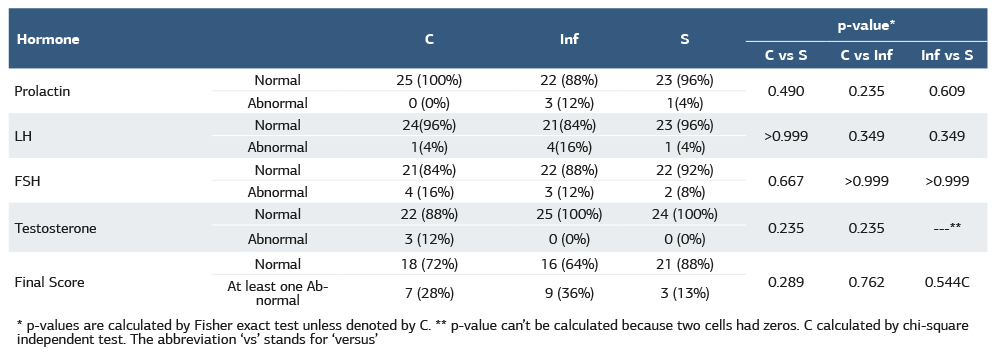

In Table (3), there were no significant differences among all groups. Concerning prolactin hormones, the control group does not have any abnormal subjects. However, the infertile group has abnormal subjects (12%) three times more than the smoker group (4%).

On the other hand, in the control and smokers groups, only 4% had abnormal LH levels, whereas in the infertile group, this percentage increased four times (16%). However, FSH and testosterone abnormal levels are greater in the control group (16% and 12% respectively). While infertile and smoker groups have 12% and 8% abnormal, respectively and those two groups have no subjects suffering from abnormal testosterone. Infertile groups (36%) have abnormal final scores this percentage is lower in the control group (28%) and the lowest in the smoker group (13%).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the effects of smoking and two SNPs, rs3750075 and rs25487, on male fertility. Our results show that all studied samples have normal type C/C, indicating that the FKBP6 rs3750075 SNP variations and smoking do not correlate with infertility. These results contradict a study [14] that linked male infertility to the SNP rs3750075. This lack of validation may occur for several reasons. Since the frequency of SNPs differs greatly among ethnic groups, the prevalence of rs3750075 in the Saudi population is unclear.

There is evidence that XRCC1 expresses itself more highly in the testes than it does in other body tissues. This finding raises the possibility that XRCC1 plays a crucial role in the complex process of correcting DNA damage caused by meiosis during spermatogenesis [15]. The poly ADP ribose polymerase binding domain’s codon 399, which is affected by the Arg399Gln polymorphism, undergoes an Arginine-to-Glutamine substitution that impairs the functionality and disrupts the DNA repair machinery [16]. The homozygous T/T genotype was more prevalent in the (Inf) group than in the other two groups, but these differences in genotype frequencies were not statistically significant. Also, the C/C genotype was more prevalent in the (C) group than in the (Inf) group. In agreement with our findings, researchers found no connection between this polymorphism and damage to sperm DNA or male infertility [17]. However, other research suggested that this SNP may indicate a hereditary predisposition to male infertility, namely idiopathic azoospermia and that the C allele may represent a risk gene for the condition in the Northern Chinese Han population [18]. Additionally, a study found a negative connection between this SNP and male infertility, indicating that the (C) allele may be protective in the Spanish population [19]. In the homozygote comparisons (C/C versus C/T + T/T), they observed a statistically significant result, confirming that the C/C genotype is linked to a lower incidence of male infertility [20]. The data demonstrates a similar trend, with the C/C genotype being more common in the fertile groups C and S and less common in the infected group. Interestingly, a study also suggested that XRCC1 polymorphism and exposure to polyaromatic hydrocarbons, a common by- product of tobacco smoking, might have a combined influence on male infertility [17]. To learn more about these potential gene-environment connections, it may be useful to include a group of participants who smoke but are not fertile.

Moreover, the relationship between the XRRC1 rs25487 SNP and the levels of prolactin, FSH, LH, and testosterone in the body was examined. It was demonstrated that, in comparison to the C/C and C/T groups, the testosterone levels in the T/T group were lower. There was a correlation between XRCC1 absence and higher DNA damage in sperm [21]. Furthermore, a negative correlation was observed between elevated DNA damage in sperm and testosterone levels [14]. All of these findings point to a possible association between male infertility, decreased testosterone levels, and greater sperm DNA damage caused by the T variant in XRCC1 rs25487. Conversely, there was no discernible correlation found between the levels of prolactin, LH, and FSH and the XRRC1 rs25487 SNP.

Male fertility requires the complete development of male germ cells and normal spermatogenesis, which is a complex process that depends on a balanced endocrine interplay of the hypothalamus, pituitary, and testis. The hypothalamus induces the secretion of gonadotrophins, FSH, and LH from the pituitary gland. FSH stimulates spermatogenesis directly, and LH induces testosterone production, stimulating spermatogenesis indirectly. Prolactin, another hormone secreted by the pituitary gland, controls the production of LH and FSH through a feedback mechanism on the hypothalamus. Alteration of the serum levels of these hormones may create disturbances in spermatogenesis and cause infertility in males [22]. To understand the effect of smoking on male fertility in Saudi Arabia, the levels of testosterone, LH, FSH, and prolactin in the (S) group were compared to the (C) and (Inf) groups. The (S) group showed a trend for elevated mean testosterone levels, with near-significant results. Those results are consistent with previously published data from other populations, including the large Tromsø study that included 3,427 men, which demonstrated that smokers had significantly higher total and free testosterone levels compared to men who never smoked [23]. LH levels were found to be higher in the (S) group compared to both the (C) group and (Inf) group. However, these differences were not significant. In addition, mean FSH levels were found to be higher in the (S) group compared to the (C) group and equivalent to that in the (Inf) group. These results have been supported by a study that also reported elevated levels of one or both gonadotrophins in smokers compared with non-smokers [24]. When looking at prolactin levels, the (S) group had comparable mean prolactin levels to the (C) group, which is lower than the (Inf) group.

Our data show no significant influence of smoking on hormone levels in Saudi men, even if there is a difference. Smoking is considered a major factor leading to male infertility [25]. The negative effects of smoking on male fertility have been studied worldwide by several groups that used various endpoints to assess male fertility, mainly hormone levels and sperm quality. Despite various associations suggested by these studies between smoking and the levels of testosterone, prolactin, FSH, and LH in the context of male infertility, the meta-analysis showed no significant influence, suggesting that hormone levels may not be the best predictor of the effect of smoking on male fertility, compared to other endpoints such as semen quality [25].

Conclusion

Our research indicates that smoking adversely affects certain hormones and fertility. However, no association was found between smoking and Fkbp6 (rs3750075). We observed an increased frequency of the XRCC1 rs25487 variant; nevertheless, it was not significantly associated with an increased risk of infertility among smokers.

Tables

Table 1. Genotypes and allele frequencies of XRCC1 rs25487 SNP in different study populations

* Can’t be calculated due to very low frequency. OR: odd ratio

Table 2. Comparing hormone levels among different XRCC1 rs25487 genotypes

Data are given as (Frequencies and percentages).[Min-max] =[Minimum: Maximum]. STD is the standard deviation

Table 3. Hormonal status among different groups

* p-values are calculated by Fisher exact test unless denoted by C. ** p-value can’t be calculated because two cells had zeros. C calculated by chi-square independent test. The abbreviation ‘vs’ stands for ‘versus’

References

-

Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet. 2012;380(9842):668-79. doi:10.1016/S0140 6736(12)61085X.

-

Al-Turki H. Effect of smoking on reproductive hormones and semen parameters of infertile Saudi Arabians. Urol Ann. 2015;7(1):63-6. doi:10.4103/0974 7796.148621.

-

Qutub J, Sharee M, Murad BA, et al. Smoking and infertility in Saudi Arabian males: a systematic review. J Health Sci. 2022;2(11):469-77. doi:10.52533/JOHS.2022.21121.

-

Omolaoye TS, Shahawy O, El Skosana BT, Boillat T, Loney T, Du Plessis. The mutagenic effect of tobacco smoke on male fertility. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(41):62055-66. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16331-x.

-

Al-Zahrani MH, Almutairi NM. Genetic polymorphisms of GSTM1 and GPX1 genes and smoking susceptibility in the Saudi population. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2023;15(4):180-9. doi:10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_365_23.

-

Opuwari CS, Henkel RR. An update on oxidative damage to spermatozoa and oocytes. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:9540142. doi:10.1155/2016/9540142.

-

Kaur J, Sambyal V, Guleria K, et al. Association of XRCC1, XRCC2, and XRCC3 gene polymorphism with Esophageal cancer risk. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:73-86. doi:10.2147/CEG.S232961.

-

Sherchkova TA, Grigoryan NA, Amelina MA, et al. Role of XRCC1, XPC, NBN gene polymorphisms in spermatogenesis. Gene Rep. 2021;24(1):101238. doi:10.1016/j.genrep.2021.101238.

-

Wyrwoll MJ, Gaasbeek CM, Golubickaite I, et al. The piRNA-pathway factor FKBP6 is essential for spermatogenesis but dispensable for control of meiotic LINE-1 expression in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109(10):1850-66. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.09.002.

-

Sengun DA, Tanoglu EG, Ulucan H. A novel mutation in FK506 binding protein- like (FKBPL) causes male infertility. Croat Med J. 2021;62(3):227-32. doi:10.3325/cmj.2021.62.227.

-

Ali A, Modawe G, Rida M, Abdrabo A. Prevalence of abnormal semen parameters among male patients attending the fertility center in Khartoum, Sudan. J Med Life Sci. 2022;4(1):1-8. doi:10.21608/jmals.2022.229304.

-

Durairajanayagam D. Lifestyle causes of male infertility. Arab J Urol. 2018;16(1):10-20. doi:10.1016/j.aju.2017.12.004.

-

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Obesity and reproduction: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(5):1266-85. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.018.

-

Zhang W, Zhang S, Xiao C, Yang Y, Zhoucun A. Mutation screening of the FKBP6 gene and its association study with spermatogenic impairment in idiopathic infertile men. Reproduction. 2007;133(2):511-6. doi:10.1530/REP-06-0125.

-

Parsons JL, Tait PS, Finch D, Dianova II, Allinson SL, Dianov GL. CHIP-mediated degradation and DNA damage-dependent stabilization regulate base excision repair proteins. Mol Cell. 2008;29(4):477-87. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.027.

-

Saadat M, Ansari-Lari M. Polymorphism of XRCC1 (at codon 399) and susceptibility to breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115(1):137-44. doi:10.1007/s10549-008-0051-0.

-

Ji G, Gu A, Zhu P, et al. Joint effects of XRCC1 polymorphisms and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure on sperm DNA damage and male infertility. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116(1):92-8. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq112.

-

Zheng LR, Wang XF, Zhou DX, Zhang J, Huo YW, Tian H. Association between XRCC1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and infertility with idiopathic azoospermia in northern Chinese Han males. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(4):402-7. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.06.014.

-

Garcia-Rodriguez A, de la Casa M, Serrano M, Gosálvez J, Roy Barcelona R. Impact of polymorphism in DNA repair genes OGG1 and XRCC1 on seminal parameters and human male infertility. Andrologia. 2018;50(10):e13115. doi:10.1111/and.13115.

-

Liu Z, Lin L, Yao X, Xing J. Association between polymorphisms in the XRCC1 gene and male infertility risk. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(18):e20008. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020008.

-

Wdowiak A, Raczkiewicz D, Stasiak M, Bojar I. Levels of FSH, LH and testosterone, and sperm DNA fragmentation. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35(1):73-9.

-

Gangwar PK, Sankhwar SN, Pant S, et al. Increased gonadotropins and prolactin are linked to infertility in males. Bioinformation. 2020;16(2):176-82. doi:10.6026/97320630016176.

-

Svartberg J, Jorde R. Endogenous testosterone levels and smoking in men. The fifth Tromsø study. Int J Androl. 2007;30(3):137-43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2006.00720.x.

-

Bassey I, Akpan UO, Isong IKP, Udoh AE. Passive smoking has the same negative effects on reproductive hormones in adult males as active smoking. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4(Suppl 2):30s. doi:10.1200/jgo.18.44000.

-

Bundhun PK, Janoo G, Bhurtu A, et al. Tobacco smoking and semen quality in infertile males: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):36. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6319-3.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or compareable ethical standards.

Funding

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Institutional Review Board (Date: 2021-03-18, No: 08-CEGMR-Bioeth-2021)

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge, with thanks, WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for their technical and financial support.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The corresponding author has committed to share the de-identified data with qualified researchers after confirmation of the necessary ethical or institutional approvals. Requests for data access should be directed to bmp.eqco@gmail.com

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Maryam Hassan Al-Zahrani, Nourah Shami Abosaber, Haneen Hamed Alsulami, Fawaz Edeeb Edris, Samah Al-Shankety. Investigation the effect of cigarette smoking on the FKBP6 and XRCC1 genes associated with male fertility. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(2):106-110

Publication History

- Received:

- August 22, 2024

- Accepted:

- January 23, 2025

- Published Online:

- April 22, 2025

- Printed:

- February 1, 2026