The rate of anemia in shift health workers in a university hospital

Anemia in shift health workers

Authors

Abstract

Aim Shift work systems among healthcare professionals can potentially lead to physical and psychological disorders. Changes in eating habits, irregular nutrition, and inadequate food intake may result in anemia. Through a retrospective analysis, we aimed to examine the prevalence of anemia and related disorders among healthcare shift workers.

Materials and Methods We included 132 healthy volunteers working at the university. The survey questions, consisting of descriptive information form and literature-based questions related to anemia, prepared by using Google Forms, were sent to the employees’ phones. Analyses were conducted based on the responses to the survey questions from healthcare workers.

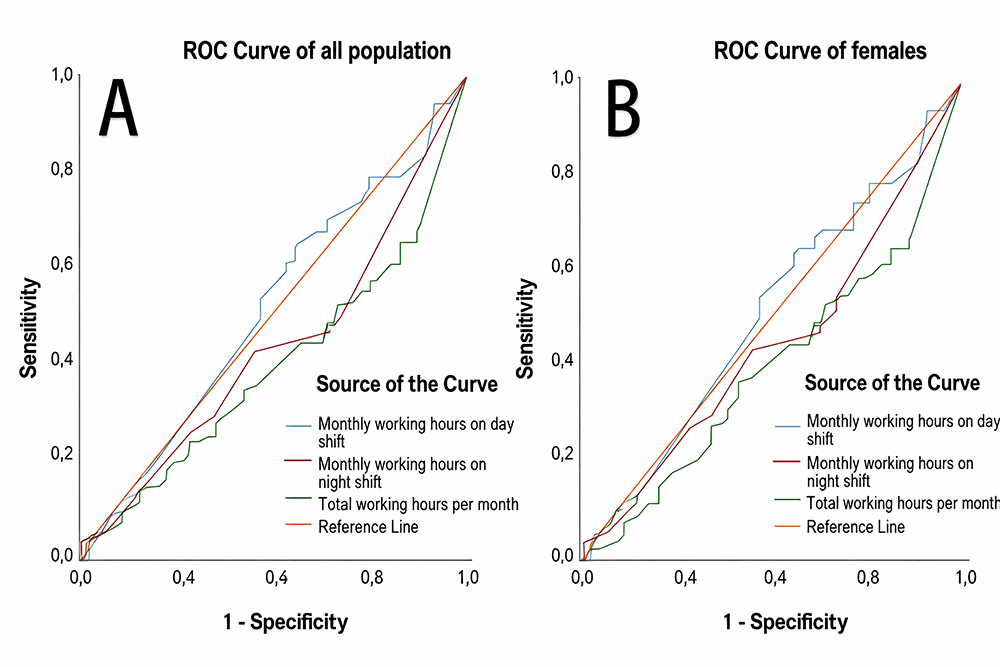

Results Among the 132 participants, more individuals worked shifts than did not (80 compared to 52). The rate of participants with anemia was 33.8% in shift workers and 42.3% in non-shift workers (p = 0.32). The incidence of anemia in females (53.3%) was significantly higher than in males (2.4%). In the ROC analysis for the presence of anemia, a total shift work duration of 157 hours was identified as the cut-off value, with a sensitivity and specificity of 43.8% and 41%, respectively. It was observed that those with thyroid disease had a higher rate of anemia compared to those without (p < 0.05).

Discussion As males constituted the majority of shift workers, analyses suggested that the risk of anemia didn’t increase despite prolonged shift work duration.

Keywords

Introduction

The shift work system is used to maintain continuous service, particularly in hospitals and other healthcare institutions, as well as in fundamental sectors such as security and industry. The implementation of shift work systems is increasing globally and is most frequently used in the health sector [1]. In a shift work system, working hours during the day, especially on the night shift, negatively affect the health of employees in physiological, psychological, and social terms. Among healthcare workers, night shifts cause circadian rhythm disorders along with changes in nutrition and sleep patterns [2]. In addition to circadian rhythm disruption, healthcare workers on night shifts frequently experience gastrointestinal issues—such as constipation and digestive difficulties—as well as various mood disorders [3]. Furthermore, shift work may increase the risk of cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Night shift work might be associated with breast cancer in women, prostate cancer, and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [4]. A study conducted among nurses identified shift work as a potential risk. A study involving nurses found that shift work may negatively affect sleep patterns, job performance, and overall quality of life [5]. Inadequate sleep in shift workers can lead to weakened immunity, metabolic issues, and nutritional deficiencies, all of which may indirectly contribute to the onset of anemia [6]. Anemia, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as hemoglobin levels or other red blood cell indices falling below a specific threshold, is a widespread condition globally. Iron deficiency anemia is the most common type, impacting roughly 30% of the world’s population [7]. Psychological disorders and circadian rhythm disruptions seen in healthcare workers on shift schedules may raise the risk of anemia by altering dietary habits and impacting iron metabolism.

Research has demonstrated that night shifts can adversely affect workers’ dietary habits, potentially resulting in deficiencies in iron and other essential vitamins [8]. Working night shifts disrupts the circadian rhythm, affecting hormone production by lowering melatonin and increasing cortisol.

Melatonin also supports the immune system and may facilitate iron absorption. The imbalance of these hormones, particularly the reduction in melatonin secretion, can decrease sleep quality, resulting in fatigue, stress, nutritional deficiencies, and anemia [9]. Hormonal imbalances observed during night shifts may affect erythropoiesis, potentially reducing red blood cell production and leading to anemia [10].

Thyroid dysfunctions, particularly hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, can lead to anemia. In hypothyroidism, decreased erythropoietin production and impaired iron metabolism, as well as in hyperthyroidism, shortened erythrocyte lifespan, can contribute to the development of anemia. Furthermore, thyroiditis may increase the risk of anemia [11].

Materials and Methods

Study design and data collection: The aim was to recruit a total of 256 healthcare workers to facilitate adequate data evaluation, as determined by power analysis (Calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.7 Software; at least 128 participants were required to be included in each group with a mean effect size (d = 0.50), alfa = 0.05 significance level, and 80% power.). The sample group consisted of all hospital employees, and only healthcare workers who worked in the shift system or had no shifts and who voluntarily completed the survey questions were included in the study as participants. The study design, participant selection, and data collection process excluded patients or members of the public. The survey questions, prepared by using ‘Google Forms’, were sent to the employees’ phones by the hospital administration. The survey questions included descriptive information form and literature-based questions related to anemia. Analyses were conducted based on the responses to the survey questions from healthcare workers. Approval for the study was obtained from the hospital administration and the ethics committee; no further consent was required from the healthcare professionals. The descriptive information form included questions on the employee’s age, gender, marital status, socio-economic status, disease diagnoses, health conditions, anemia assessment, and shift-work-related factors. The anemia-related questions were developed based on existing literature.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, USA). Histograms, probability plots, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to assess whether the variables followed a normal distribution. Frequency tables summarized categorical variables, and statistical differences between them were evaluated using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (25-75%), depending on the normality of their distributions. To assess differences between groups in terms of numerical variables, the independent samples t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used. ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) analyses were conducted to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of continuous variables related to shift work durations in indicating the presence of anemia. A p < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Afyon Health Science University (Date: 2023-11-03, No: 2023/484).

Results

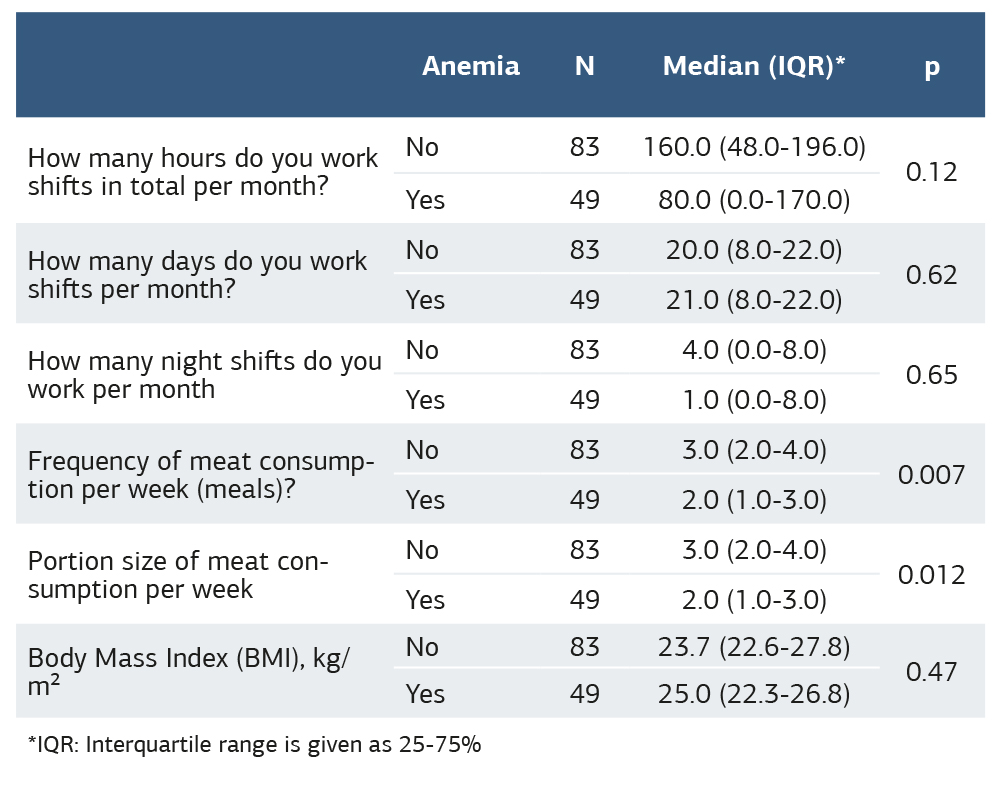

Of the total 132 volunteer participants, 60.6% were shift workers, and the rate of participants with anemia among shift workers was 33.8% (Supplementary Table S1). The incidence of anemia in females (53.3%) was significantly higher than in males (2.4%) (p < 0.001). While 37.1% of participants were diagnosed with iron deficiency, 38.6% were diagnosed with vitamin deficiency (including B12, folic acid, and other vitamins). When comparing occupational groups for anemia prevalence, nurses exhibited a significantly higher rate of anemia, which was statistically significant (p = 0.0002) (Supplementary Table S1). Anemia was observed in 57.9% of participants with thyroid disease and 33.6% of those without (p = 0.004). The prevalence of anemia was higher among individuals who consumed tea with meals compared to those who drank tea immediately after or 1–2 hours following meals (p = 0.006, Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, anemia was significantly more common in participants with a family history of iron deficiency anemia than in those without such a history (p < 0.001). Both the mean and median number of weekly meals and portions of red meat consumed were significantly lower in the anemic group compared to the non-anemic group (p < 0.05 for both, Table 1). The median total shift work time per month was 80.0 (IQR: 0.0- 170.0) hours in those with anemia and 160.0 (IQR: 48.0-196.0) hours in those without anemia (p > 0.05, Table 1).

In the ROC analysis for total working hours with shifts, day and night working hours, and the presence of anemia, 43.1% sensitivity, and 41% specificity rates were determined at a cut- off value of 157 hours for total working hours with shifts (AUC: 0.380, CI: 0.277 - 0.482, p = 0.022). A value above 16.5 hours was associated with the absence of anemia. ROC analysis was also performed to assess the presence of anemia in women and continuous variables related to shift work, including the total duration of shift work, number of day and night shifts, and presence of anemia (p > 0.05 for all), Figure 1, Supplementary Table S2).

The mean (143.55 ± 82.44 versus 111.93 ± 95.59 hours, p = 0.02) and median (176.0 IQR: 0.50 - 182.0 versus 130.0 IQR: 65.0 - 196.0, p = 0.01) values of total shift work time per month were higher in men (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

In the study, the majority of participants were women (68.1%). Most participants were shift workers (60.6%), with the majority being male. Additionally, men had a longer total shift working time. The lower anemia rate among shift workers compared to non-shift workers was attributed to the predominance of male participants among shift workers. While anemia is more prevalent among females, the limited total number of participants and the shorter total shift work duration for women precluded the identification of a significant cut-off value for anemia in the ROC analysis conducted for total shift work duration, daytime work hours, and nighttime work hours among female participants. Shift work is quite common among healthcare workers. Unbalanced eating patterns, limited access to healthy foods, night shifts, and psychological problems increase the risk of coronary heart disease, metabolic syndrome, and even cancer, and the absorption of vitamins and minerals may be adversely affected. It was reported that women shift workers have a greater risk of poor sleep quality, coronary heart disease, metabolic disorders, and breast cancer [12].

Shift work may increase the risk of anemia due to its association with metabolic diseases. Additionally, chronic inflammation in metabolic diseases can suppress iron absorption by altering hepcidin regulation, leading to the development of anemia in chronic disease. In a recent study, among individuals of European ancestry, hypothyroidism was associated with a higher risk of anemia independent of inflammation and lifestyle [13]. In our participants, it was observed that those with thyroid disease had a higher rate of anemia compared to those without. Consistent with the literature, it has been observed that thyroid pathologies, among metabolic diseases, contribute to the risk of anemia.

In healthcare personnel working in shifts, psychological disorders like depression and anxiety may increase the risk of anemia by affecting dietary habits [14]. Although awareness of anemia among healthcare workers is high, shift work systems can lead to irregular food intake and disrupted sleep patterns. In our study, 37.1% of participants reported being diagnosed with iron deficiency, while 38.6% reported being deficient in vitamins. The median values of weekly red meat consumption in terms of meals and portions were significantly lower in the anemic group.

Studies have suggested that black tea, rich in tannins, can inhibit the absorption of non-heme iron. Consistently drinking large amounts of tea with meals may contribute to iron deficiency anemia [15]. In our study, anemia was significantly more prevalent among participants who consumed tea with meals compared to those who drank tea immediately or 1–2 hours after meals, supporting the negative impact of tea consumption during meals.

Limitations

In our study, the fact that not all volunteer participants were shift workers created a heterogeneous population, and the fact that most shift workers among the participants were male, along with the low anemia rate observed in males, led to the conclusion that long-term shift work does not increase the risk of anemia. Additionally, our inability to reach the targeted volunteer participants may have led to insufficient data for accurate analysis and caused unexpected study results. In this regard, there is a need for studies involving a larger number of participants and specific groups.

Conclusion

To contribute to the literatüre in terms of the rate of anemia in shift workers, however, we were unable to reach a sufficient number of participants, and the target population consisted of individuals from all occupational groups, regardless of gender; the relatively high rate of anemia among nurses was found to be statistically significant. The fact that most of the night shift workers were male and anemia was less common in men, it was found that the rate of anemia did not increase despite the long shift hours. In addition, low weekly consumption of red meat meals and portions was found to be associated with an increased risk of anemia. More meaningful results may be obtained through randomized studies involving a larger number of participants with homogeneous groups.

Figures

Figure 1. ROC analysis for total working hours with shifts, day and night working hours for the presence of anemia

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of median values of continuous variables according to anemia status

*IQR: Interquartile range is given as 25-75%

References

-

Sooriyaarachchi P, Jayawardena R, Pavey T, King NA. Shift work and the risk for metabolic syndrome among healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Obes Rev. 2022;23(10):e13489. doi:10.1111/obr.13489.

-

Varlı SN, Mortaş H. The effect of 24 h shift work on the nutritional status of healthcare workers: an observational follow-up study from Türkiye. Nutrients. 2024;16(13):2088. doi:10.3390/nu16132088.

-

Moreno CRC, Marqueze EC, Sargent C, Wright KP, Ferguson SA, Tucker P. Working time society consensus statements: evidence-based effects of shift work on physical and mental health. Ind Health. 2019;57(2):139-57. doi:10.2486/indhealth.SW-1.

-

Czyż-Szypenbejl K, Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W. The impact of night work on the sleep and health of medical staff—a review of the latest scientific reports. J Clin Med. 2024;13(15):4505. doi:10.3390/jcm13154505.

-

Selvi Y, Özdemir P, Özdemir O, Aydın A, Beşiroğlu L. Sağlık çalışanlarında vardiyalı çalışma sisteminin sebep olduğu genel ruhsal belirtiler ve yaşam kalitesi üzerine etkisi [General mental symptoms caused by shift work system in healthcare workers and its effect on quality of life]. Dusunen Adam J Psychiatr Neurol Sci. 2010;23(4):238-43. doi:10.5350/DAJPN2010230403.

-

Sun M, Feng W, Wang F, et al. Meta-analysis on shift work and risks of specific obesity types. Obes Rev. 2018;19(1):28-40. doi:10.1111/obr.12621.

-

Warner MJ, Kamran MT. Iron deficiency anemia. [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448065/.

-

Kulak AY, Yeşil E. The relationship between nutritional status and cognitive functions of shift health workers. J Turk Sleep Med. 2022;9(3):269-77. doi:10.4274/jtsm.galenos.2022.48278.

-

Szataniak I, Packi K. Melatonin as the missing link between sleep deprivation and immune dysregulation: a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(14):6731. doi:10.3390/ijms26146731.

-

Pereira H, Feher G, Tibold A, Monteiro S, Costa V, Esgalhado G. The impact of shift work on occupational health indicators among professionally active adults: a comparative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11290. doi:10.3390/ijerph182111290.

-

Gül N. Subakut tiroidit hastalarinda anemi sıklığı ve hastalık aktivitesi ile ilişkisi [Frequency of anemia in patients with subacute thyroiditis and its relationship with disease]. Thyroid Dis. 2018;81(2):46-50. doi:10.26650/IUITFD.382521.

-

Chung SA, Wolf TK, Shapiro CM. Sleep and health consequences of shift work in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;18(7):965-77. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0742.

-

van Vliet NA, Kamphuis AEP, den Elzen WPJ, et al. Thyroid function and risk of anemia: a multivariable-adjusted and mendelian randomization analysis in the UK Biobank. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(2):e643-52. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab674.

-

Geniş B, Can Ö, Demirci Z. Factors affecting mental status in health workers and the effects of shift work system. J Psy Nurs. 2020;11(4):275-83. doi:10.14744/phd.2020.60590.

-

Elmas C, Gezer C. Çay bitkisinin (camellia sinensis) bileşimi ve sağlık ttkileri [Composition and health effects of tea plant (Camellia sinensis)]. Academic Food. 2019;17(3):417-28. doi:10.24323/akademik-gida.647733.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Afyon Health Science University (Date: 2023-11-03, No: 2023/484)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Nermin Keni Begendi, Mustafa Duran, Yaşar Culha. The rate of anemia in shift health workers in a university hospital. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(2):144-147

Publication History

- Received:

- October 7, 2025

- Accepted:

- November 24, 2025

- Published Online:

- January 21, 2026

- Printed:

- February 1, 2026