SII and SIRI in the Follow-up of Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients on Anti-TNF Therapy

Inflammation markers in ankylosing spondylitis

Authors

Abstract

Aim Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS), a form of inflammatory arthritis of the spine, often presents as chronic back pain before age 45. This study examines the role of the Systemic Immune Response Index (SII) and Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in diagnosing AS and monitoring treatment in patients receiving anti-TNF-α therapy.

Methods This study included 90 participants (45 AS patients on anti-TNF therapy and 45 healthy controls). Age, gender, demographic data, inflammation markers (neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, ESR, CRP), and disease activity levels (using BASDAI) were retrospectively collected. SII and SIRI values were measured at baseline and after 3 and 6 months of TNF therapy.

ResultsThe SII and SIRI values of the patient group at baseline were higher than those of the healthy group (p < 0.001). ROC analysis of the discrimination power of the data of AS patients who were started on anti-TNF drugs at the time of treatment initiation, on the healthy group, showed that the success of SII and SIRI values in classification was statistically significant (p < 0.001). According to this model, the pre-treatment SII value of the patient group had a sensitivity of 68.9% and a specificity of 86.7%, and the SIRI value had a sensitivity of 62.2% and a specificity of 82.2%. SII and SIRI values measured at 3 and 6 months after treatment were significantly lower than baseline (p < 0.001). SII and SIRI were positively correlated with CRP and ESR.

Conclusion SII and SIRI may be a reliable and easily accessible biomarker for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with AS.

Keywords

Introduction

Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory disease of the spine that typically causes chronic back pain before the age of 45. It is often accompanied by one or more extraspinal pathologies, such as synovitis, enthesitis, and dactylitis, as well as uveitis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with this pathology often possess the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 gene. Additionally, those with active inflammatory disease frequently exhibit a high acute phase response.1,2

Currently, there is no specific standardized laboratory test available for detecting and monitoring AS. The commonly used tests to indicate inflammation are acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.3 These tests can be helpful in determining the level of inflammation, changes in disease activity over time, and prognosis. Although useful in assessing the degree of inflammation and prognosis, these tests have been found to have low sensitivity and specificity.4,5 Furthermore, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) is commonly used in daily practice to measure the clinical activity of the disease.6 In recent years, there has been a suggestion that certain markers of systemic inflammation, which can be easily extracted from the hemogram using various mathematical formulas, can serve as independent predictors of prognosis and mortality in both benign and malignant diseases.7,8,9 The Systemic Immune Inflammation Index (SII) and Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) are calculated based on hemogram parameters and are thought to have a strong relationship with inflammation. They are used to assess the prognosis of diseases. SII has been reported as a strong prognostic marker in many types of cancer and has been found to be correlated with disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.10,11 SIRI may serve as a prognostic marker in pancreatic cancer,12 is linked to higher mortality rates in stroke patients,13 and is correlated with disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).14

The aim of this study is to investigate the severity of disease and the use of SII and SIRI in disease follow-up in AS patients started on anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drug treatment according to follow-up at baseline (month 0), month 3, and month 6 of treatment. In addition, we will try to evaluate whether SII and SIRI correlate with disease activity in patients with AS and the possible use of SIRI as a marker in treatment follow-up.

Materials and Methods

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the data of 45 patients diagnosed with AS and who received anti-TNF drug treatment and 45 healthy participants who were admitted to the Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic of Mersin University Faculty of Medicine Hospital between 2011 and 2021. The participants were all over 18 years old. Individuals with any hematologic/oncologic disease or infection that may affect hemogram parameters, liver or kidney failure, or possible pregnancy were excluded from the study. The patient group included patients who had previously received at least two different NSAIDs, did not respond to these treatments, and had a BASDAI score ≥ 4.0 and an indication for anti-TNF drug initiation. Demographic data such as age, gender, single-value measurement of the healthy group, and hemogram, sedimentation, CRP, SII, SIRI, NLR, PLR, LMR, and BASDAI measurements of the patients before, 3 months, and 6 months after starting anti-TNF drug treatment were retrospectively screened and recorded.

The Parameters Studied are as Follows

• The formula for the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is calculated by multiplying the neutrophil count by the platelet count and then dividing the result by the lymphocyte count.

• The Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) is calculated by multiplying the Neutrophil count by the Monocyte count and dividing the result by the Lymphocyte count.

• The Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) is calculated by dividing the Neutrophil count by the Lymphocyte count.

• The Platelet Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) is calculated by dividing the Platelet count by the Lymphocyte count.

• The Lymphocyte Monocyte Ratio (LMR) is calculated by dividing the Lymphocyte count by the Monocyte count.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mersin University (Date: 2021-12-15, No: 2021/760).

Statistical Analysis

The study data were analyzed using SPSS 22 and MedCalc 20.008. The data were summarized using mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values. The normality assumption was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Pairwise group comparisons for normally distributed variables were conducted using Student’s t-test, while non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Pearson Correlation test was used to establish the relationship between continuous measurements. The Repeated Measures ANOVA test was used to compare measurements taken at different time points. The Bonferroni test was used to determine which comparisons caused the significant differences found as a result of ANOVA. Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) analysis was used to determine the discriminative power between patients and healthy subjects for each measurement time. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Reporting Guidelines

This study was reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.

Results

A total of 45 patients diagnosed with AS and receiving anti-TNF medication, and 45 healthy participants were included in our study. In the control group, 23 were male and 22 were female, and the mean age of 36.3 years ± SD (min: 19-max: 62). In the patient group, 29 of the patients were male and 16 were female, and the mean age was 41.4 years ± SD (min: 22-max: 72).

A statistically significant decrease was observed in the SII and SIRI values of patients with ankylosing spondylitis at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months after treatment (p < 0.001). In addition, statistically significant differences were found in CRP, ESR, BASDAI, NLR, PLR, and LMR values between the two groups (p < 0.001), as shown in Supplementary Table 1.

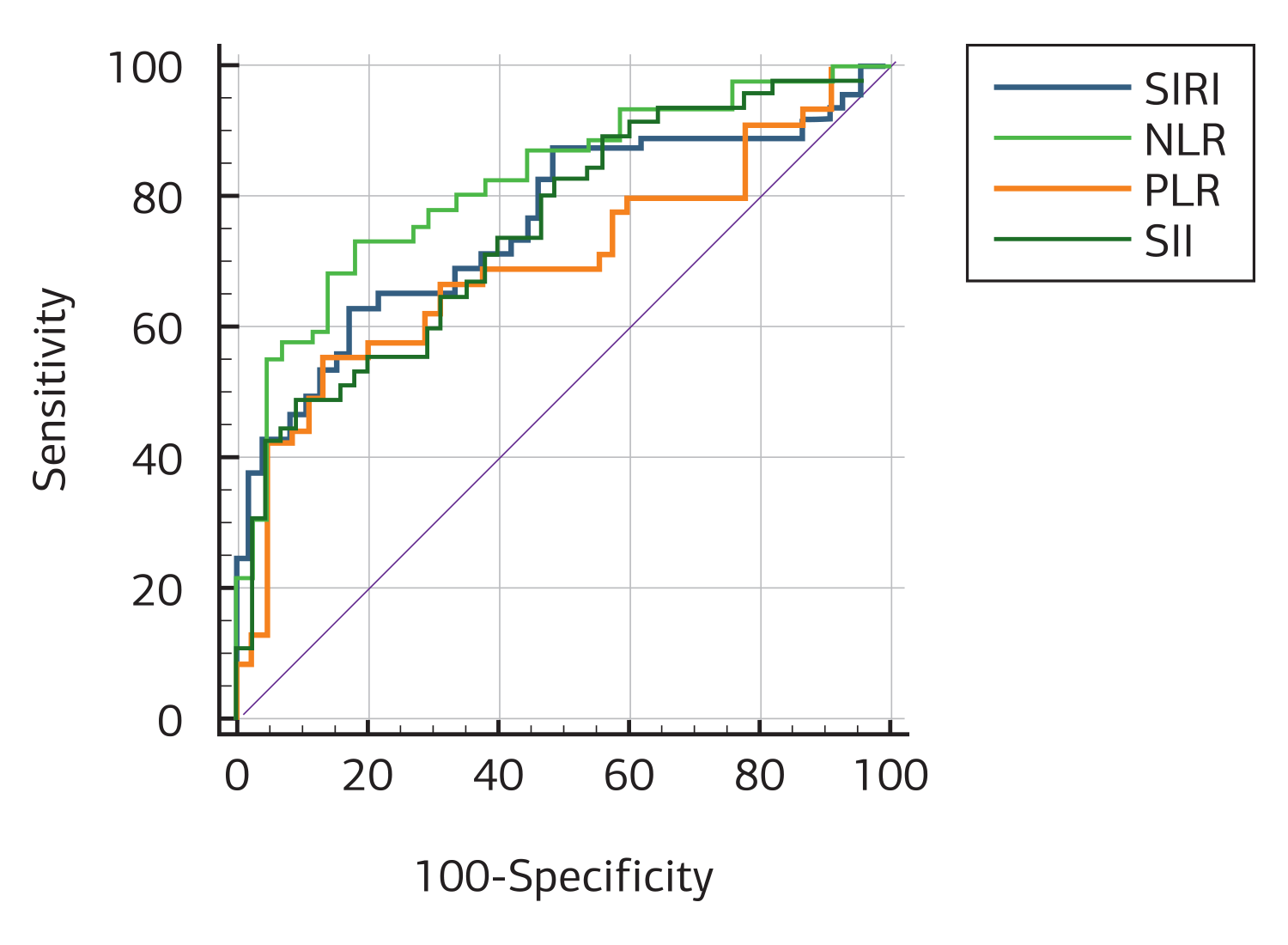

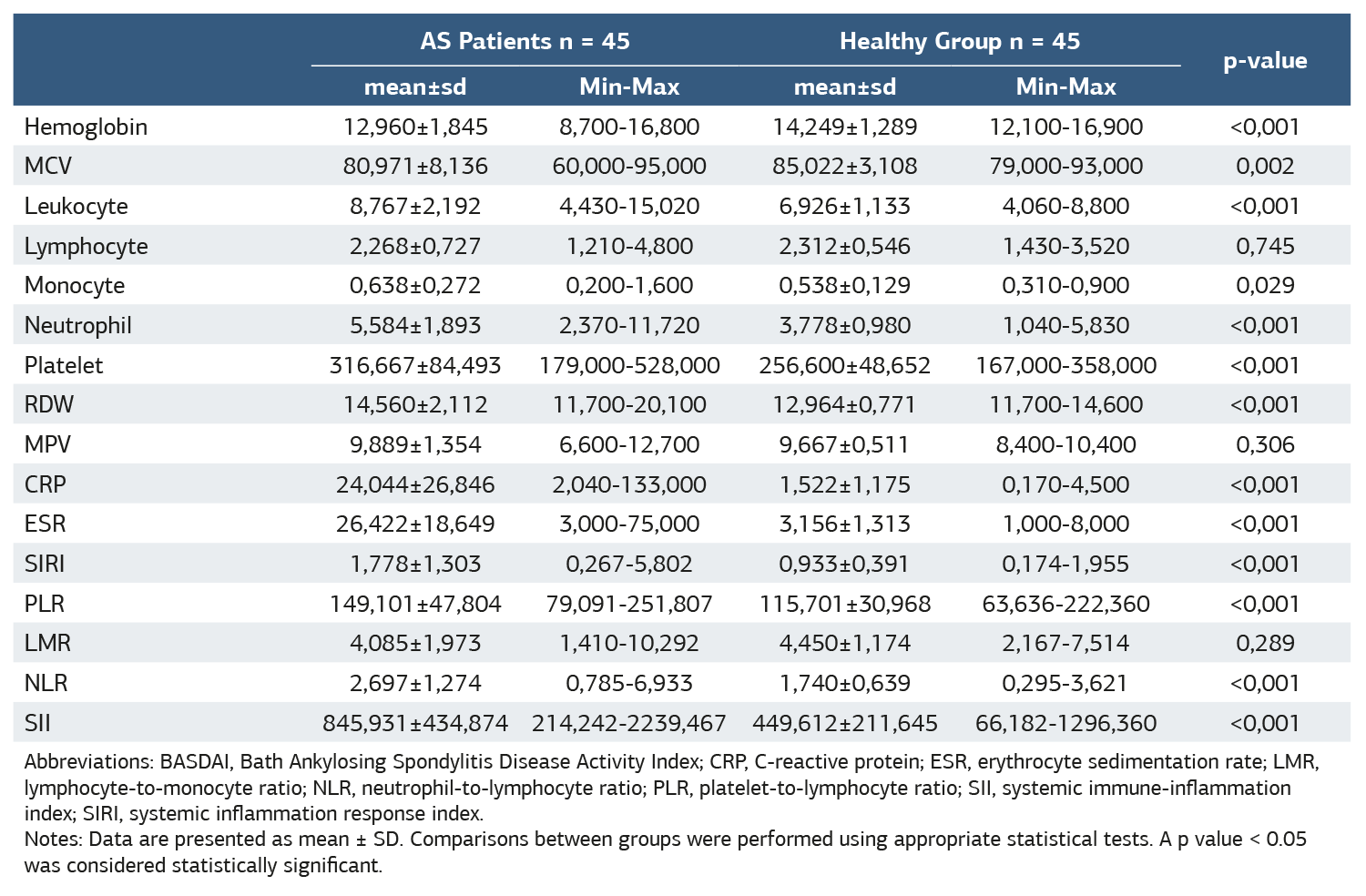

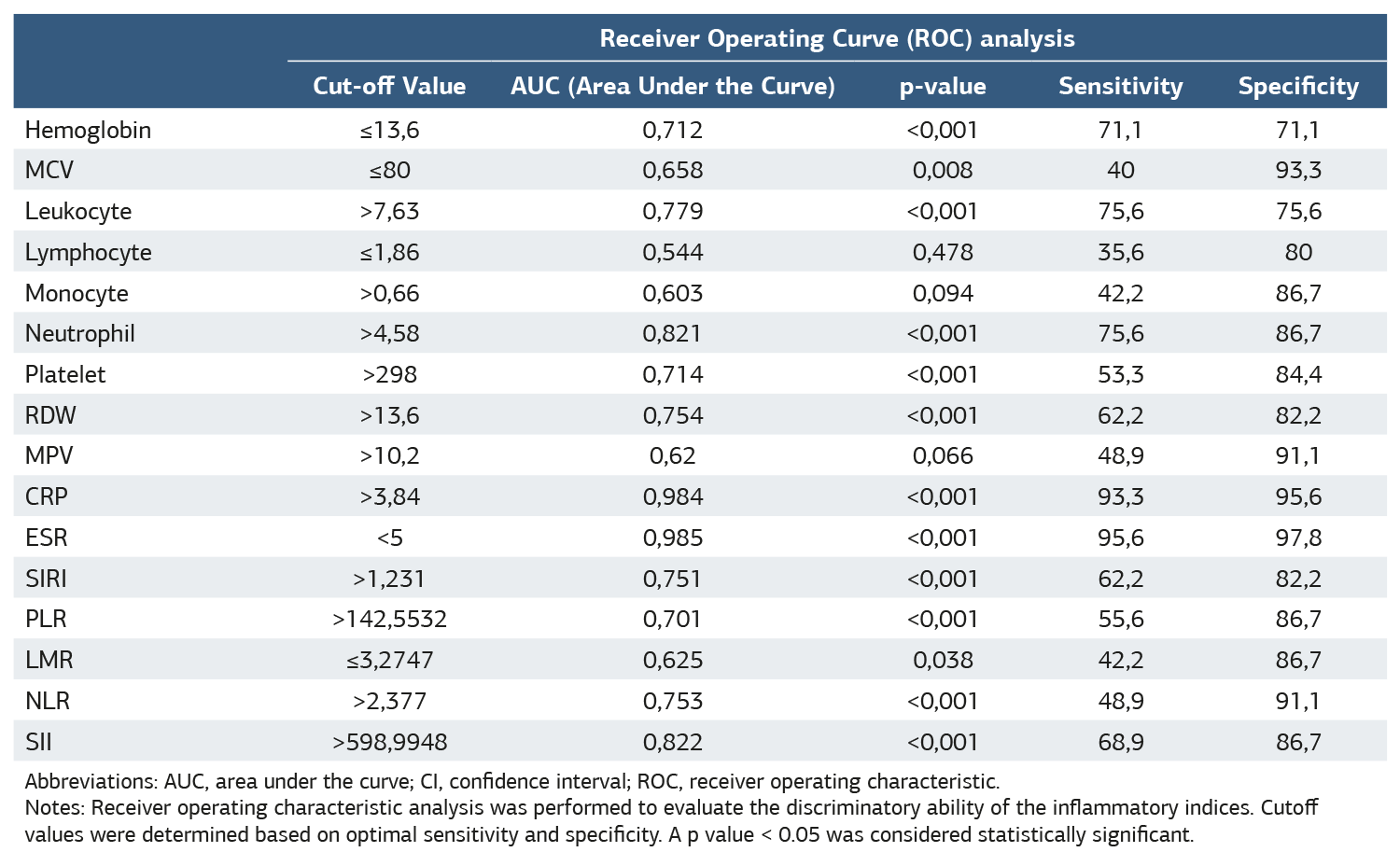

The hemogram parameters of the healthy group and AS patients at the beginning of treatment were analyzed. The results showed that AS patients had statistically significantly higher mean values of SII, SIRI, CRP, ESR, NLR, and PLR compared to the healthy group (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) analysis of the discriminative power of hemogram, CRP, ESR, SIRI, PLR, NLR, LMR, and SII values on the healthy and patient groups was performed (Figure 1). SII had a sensitivity of 68.9% and a specificity of 86.7% with a cut-off value of 589.9948, while SIRI had a sensitivity of 62.2% and a specificity of 86.6% with a cut-off value of 1.231 . In the analysis of the inflammatory markers in our study, the most sensitive biomarkers were SII, SIRI, and PLR, whereas the most specific biomarkers were NLR, SII, PLR, LMR, and SIRI (Table 2). Logarithmic correlation analysis was performed between SIRI, PLR, LMR, NLR, NLR, and SII measurements and BASDAI, CRP, and ESR measurements at the start of anti-TNF treatment. A statistically significant, linear, positive, and moderate correlation was found between SIRI measurements taken at the beginning of treatment and CRP (p = 0.000; r = 0.503) and sedimentation (p = 0.009; r = 0.385) measurements. A statistically significant, linear positive, and moderate correlation was found between the SII measurements taken at the beginning of treatment and CRP (p = 0.031; r = 0.322) and sedimentation (p = 0.004; r = 0.424) measurements.

Discussion

Although recent studies have begun to explore the role of the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in ankylosing spondylitis (AS), data remain limited, particularly concerning their utility in monitoring treatment response to anti-TNF therapy. The present study contributes to this growing body of evidence by evaluating the clinical usefulness of SII and SIRI in AS patients receiving anti-TNF treatment.

SII was first described by Bo Hu et al. as a useful prognostic factor in hepatocellular cancer patients.15 Yang et al. published a comprehensive meta-analysis in 2018. The study found that high SII values were associated with worse median survival, worse progression-free survival, and worse cancer-specific or disease-free overall survival in cancer patients.16 However, the cut-off points for the SII values varied among the studies, but this did not affect the results of the meta-regression analysis. This finding suggests that future clinical trials should consider adjusting the optimal cut-off point.16

Yoshikawa et al. evaluated SII and NLR values in 574 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and found that SII was more strongly associated with disease activity compared to NLR.11 Similarly, Tanacan et al. retrospectively analyzed 130 patients with active Behçet’s Disease (BD) and 63 patients with inactive BD. Statistically significantly higher SII values were found in the group with active BD compared to the group with inactive BD.17

Tezcan et al. demonstrated that both SII and SIRI were significantly elevated in patients with AS compared to healthy controls. While SII levels significantly decreased following anti-TNF therapy, SIRI levels remained persistently high. The reduction in SII was particularly significant among HLA-B27-positive patients. Moreover, elevated SII and SIRI values were associated with active disease status and showed positive correlations with conventional inflammatory markers, including ESR, CRP, and BASDAI.18

In a retrospective cohort analysis by Yu-Jen Pan et al., involving rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (b/tsDMARDs), SII levels were significantly reduced following treatment. Moreover, higher baseline SII values were associated with greater decreases in erythrocyte sedimentation rate at three months, and SII demonstrated a moderate correlation with C-reactive protein during follow-up.19

In this study, we evaluated the relationship between disease activity and SII measurement levels in AS patients who were started on anti-TNF drug therapy. Our findings showed that SII levels were significantly higher in AS patients who received anti-TNF medication compared to healthy individuals. In previous studies, SII levels were found to be higher in patients with AS than in healthy controls,18,20,21 supporting the findings in our study.

Wu et al. found that SII was the most effective biomarker for differentiating disease activity in AS patients, outperforming CRP and ESR, with sensitivity and specificity values of 86.4% and 83.3%, respectively.20 Our study also found statistically significant success in the classification of AS patients using the SII value. These results support the use of SII as a means of distinguishing AS patients from healthy controls.

In a study conducted by Okutan et al. on patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a significant positive correlation was reported between the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), and disease activity. The predictive accuracy was calculated as 75.26% for SII and 72.16% for SIRI. In the ROC analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) values were 0.717 for both SII and SIRI, with cutoff values of 611.45 and 1.18, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity were determined as 57.81% and 60.61% for SII, and 59.38% and 63.64% for SIRI.22

Qi et al. first investigated SIRI measurement in patients with pancreatic cancer. The study found that SIRI has prognostic value in terms of mean survival and time to progression. Additionally, the study suggested that SIRI may reflect local immune response, systemic inflammation status, and tumor burden.12 Xu et al. published a multi-center retrospective study of 1499 RA patients and 366 healthy volunteers, examining the NLR, LMR, PLR, and SIRI values of the participants. The results showed that SIRI and NLR measurements were able to distinguish RA patients from healthy controls.14 It was also found that SIRI and PLR measurements were positively correlated with disease activity in RA patients. These findings suggest that SIRI measurement can be used as a suitable biomarker to aid in the diagnostic process and to indicate the disease activity of RA.14 In a retrospective study by Zhang et al., SIRI was found to be associated with all-cause mortality in stroke patients, and a positive correlation was found between SIRI elevation and mortality. In addition, high SIRI measurement values were found to be associated with high sepsis risk and high stroke severity.

Jin et al. retrospectively examined the SIRI measurements of 48 RA patients with ischemic stroke and a control group of 48 healthy participants. They reported that SIRI was statistically significantly higher in RA patients with ischemic stroke than in the healthy group, and SIRI may be an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke in RA patients.23

In the study by Dede et al., the sensitivity and specificity of SIRI measured in AS patients were 69.2% and 68.6%, respectively. In this study, 44.2% of the patients were receiving anti-TNF drug treatment.21 Similarly, in our study, SIRI measurement was statistically significant in differentiating the patient and healthy groups. In our study, the sensitivity and specificity of SIRI were calculated as 62.2% and 82.2%, respectively.

In a multicenter study by Morariu et al., SII was found to be significantly correlated with the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, while SIRI was associated with the Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index. Moreover, higher baseline SIRI levels were identified as independent predictors of super-responder status in patients treated with biologics.24

In our longitudinal analysis, SII and SIRI values changed over time in AS patients who began anti-TNF therapy. Statistically significant differences were observed between baseline and the third and sixth months of treatment for SII.

Based on our results, SII and SIRI measurements may serve as biomarkers that significantly contribute to the diagnostic process of AS patients. They may also aid clinicians in monitoring AS patients with high disease activity, particularly those who are starting anti-TNF drug therapy.

The positive correlation between SII and SIRI values and CRP and ESR values found in our study suggests that SII and SIRI may be closely related to inflammatory status in AS patients. Additionally, in some AS patients, acute-phase reactants may be normal despite active disease, high disease activity, and severe symptoms.5,25 In such cases, SII and SIRI may provide additional insights into inflammatory status. Furthermore, as the BASDAI is a subjective measure, it is possible for patients to exaggerate their symptoms or inaccurately assess their pain due to other mechanical causes or fibromyalgia. SII and SIRI could offer more objective indicators of disease activity in these scenarios.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective nature, evaluation of data from a single center, and limited sample size. To make strong interpretations of the significance of the biomarkers evaluated in this study and to obtain other supporting evidence, larger studies involving multiple centers are needed. Furthermore, to strengthen the role of SII and SIRI measurements in the diagnosis and follow-up of AS, it is important to conduct longer patient follow-up and include radiographic endpoints for support.

Conclusion

SII and SIRI measurements are cost-effective, easily accessible, and objective tools that provide clinicians with convenient diagnostic and follow-up options for AS patients undergoing anti-TNF therapy.

Figures

Figure 1. Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis of the discriminative power of SIRI, PLR, NLR, LMR, and SII values on the healthy and patient groups

Tables

Table 1. Hemogram, CRP, ESR, SIRI, PLR, LMR, NLR, and SII values of the healthy group and all AS patients at the beginning of treatment were measured

Abbreviations: BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LMR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index. Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were performed using appropriate statistical tests. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 2. Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis of the discriminative power of hemogram, CRP, ESR, SIRI, PLR, NLR, LMR, and SII values between healthy and patient groups

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; ROC, receiver operating characteristic. Notes: Receiver operating characteristic analysis was performed to evaluate the discriminatory ability of the inflammatory indices. Cutoff values were determined based on optimal sensitivity and specificity. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

References

-

Deodhar A, Mease PJ, Reveille JD, et al. Frequency of axial spondyloarthritis diagnosis among patients seen by US rheumatologists for evaluation of chronic back pain. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(7):1669-76. doi:10.1002/art.39612

-

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(1):25-31. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.133645

-

Gökmen F, Akbal A, Reşorlu H, et al. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio connected to treatment options and inflammation markers of ankylosing spondylitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2015;29(4):294-8. doi:10.1002/jcla.21768

-

Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nakache JP, et al. Clinical relevance of C-reactive protein in axial involvement of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):971-4.

-

Chen CH, Chen HA, Liao HT, Liu CH, Tsai CY, Chou CT. The clinical usefulness of ESR, CRP, and disease duration in ankylosing spondylitis: the product of these acute-phase reactants and disease duration is associated with patient’s poor physical mobility. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(7):1263-7. doi:10.1007/s00296-015-3214-4

-

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(12):2286-91.

-

Kinoshita A, Onoda H, Imai N, et al. Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(6):988-93. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.354

-

Kokulu K, Günaydın YK, Akıllı NB, et al. Relationship between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute pancreatitis and the severity and systemic complications of the disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29(6):684-91. doi:10.5152/tjg.2018.17563

-

Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, et al. An inflammation-based prognostic score (mGPS) predicts cancer survival independent of tumour site: a Glasgow ınflammation outcome study. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(4):726-34. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6606087

-

Chen JH, Zhai ET, Yuan YJ, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(34):6261-72. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6261

-

Yoshikawa T, Furukawa T, Tamura M, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index in rheumatoid arthritis patients: relation to disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(Suppl 2):325. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.4481

-

Qi Q, Zhuang L, Shen Y, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2158-67. doi:10.1002/cncr.30057

-

Zhang Y, Xing Z, Zhou K, Jiang S. The predictive role of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in the prognosis of stroke patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1997-2007. doi:10.2147/CIA.S339221

-

Xu Y, He H, Zang Y, et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) as a novel biomarker in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multi-center retrospective study. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(7):1989-2000. doi:10.1007/s10067-022-06122-1

-

Hu B, Yang XR, Xu Y, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):6212-22. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0442

-

Yang R, Chang Q, Meng X, Gao N, Wang W. Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in cancer: a meta-analysis. J Cancer. 2018;9(18):3295-302. doi:10.7150/jca.25691

-

Tanacan A, Uyanik E, Unal C, Beksac MS. A cut-off value for systemic immune-inflammation index in the prediction of adverse neonatal outcomes in preterm premature rupture of the membranes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46(8):1333-41. doi:10.1111/jog.14320

-

Tezcan D, Körez MK, Hakbilen S, Kaygisiz ME, Gülcemal S, Yilmaz S. Clinical usefulness of hematologic indices in evaluating response to treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alfa agents and disease activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Contemp Med. 2024;14(1):37-45. doi:10.16899/jcm.1415761

-

Pan YJ, Su KY, Shen CL, Wu YF. Correlation of hematological indices and acute-phase reactants in rheumatoid arthritis patients on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: A retrospective cohort analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;12(24):7611. doi:10.3390/jcm12247611

-

Wu J, Yan L, Chai K. Systemic immune-inflammation index is associated with disease activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35(9):e23964. doi:10.1002/jcla.23964

-

Dede BT, Bulut B, Oğuz M, Bağcıer F, Aytekin E. Evaluation of the systemic immüne-inflammation index and systemic inflammatory response index in ankylosing spondylitis patients. İstanbul Med J. 2023;24(4):352-6. doi:10.4274/imj.galenos.2023.32798

-

Okutan İ, Aci R, Keskin A, Bilgin M, Kızılet H. New inflammatory markers associated with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: pan-immune- inflammation value, systemic immune-inflammation index, and systemic inflammation response index. Reumatologia. 2024;62(6):439-46. doi:10.5114/reum/196066

-

Jin Z, Hao D, Song Y, Zhuang L, Wang Q, Yu X. Systemic inflammatory response index as an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A retrospective study based on propensity score matching. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(10):3919-27. doi:10.1007/s10067-021-05762-z

-

Morariu SH, Cotoi OS, Tiucă OM, et al. Blood-count-derived inflammatory markers as predictors of response to biologics and small-molecule inhibitors in psoriasis: A multicenter study. J Clin Med. 2024;13(14):3992. doi:10.3390/jcm13143992

-

Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, Sieper J. Prediction of a majör clinical response (BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis factor α blockers in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(6):665-70. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.016386

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mersin University (Date: 2021-12-15, No: 2021/760)

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.A., K.T.

Methodology: A.A.

Formal Analysis: D.H.S.

Investigation: D.H.S., A.A., R.A.O.

Data Curation: A.A., R.A.O.

Writing – Original Draft Preparation: A.A.

Writing – Review & Editing: K.T., R.A.O.

Supervision: K.T.

Abbreviations

AS: ankylosing spondylitis

AUC: area under the curve

BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

CRP: C-reactive protein

ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate

LMR: lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

MCV: mean corpuscular volume

MPV: mean platelet volume

NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

RDW: red cell distribution width

ROC: receiver operating characteristic

SD: standard deviation

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index

SIRI: systemic inflammation response index

TNF: tumor necrosis factor

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Abdurrahman Aykut, Kenan Turgutalp, Damla Hazal Sucu, Ramazan Aytaç Olacak. SII and SIRI in the follow-up of ankylosing spondylitis patients on Anti-TNF therapy. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(Suppl 1):S1-6

Publication History

- Received:

- November 3, 2024

- Accepted:

- June 2, 2025

- Published Online:

- June 14, 2025

- Printed:

- February 20, 2026