Institutional preparedness and management of intraoperative cardiac arrest: a survey

Intraoperative cardiac arrest

Authors

Abstract

Aim Cardiac arrest in the operating room is rare but the worst event during anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiologists who are familiar with the patient’s medical history and risks of the ongoing surgery mainly witness intraoperative cardiac arrest. There is limited evidence to guide the management of intraoperative arrest specifically. As in any other setting, cardiopulmonary resuscitation has to be initiated as soon as cardiac arrest is recognized. This includes the performance of efficient chest compressions, ensuring ventilation, and defibrillation as rapidly as possible if ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia is present. In this survey study, we aimed to determine the presence of adequate equipment and management of intraoperative cardiac arrest in Türkiye.

Methods We conducted a web-based survey among members of the Turkish Society of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation. The survey consisted of 37 closed-answer questions. All the feedback and answers to the survey questions were statistically analyzed and recorded.

Results A total of 252 participants completed the survey. The most common reasons were hypovolemia, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and others. The mortality rate was found to be 55.6%, of which 27.08% was immediately in the operating room. Out of 252 participants,224 (88.9%) reported that they received advanced life support education. Among these educated participants, only 32.9% got a specific chapter about intraoperative cases. Ratio for the follow-up of guidelines was 94.8%. Sixty-eight physicians (29.8%) received the training in less than one year,108 (47.4%) in between 1 and 5 years and 52 (22.8%) in between 5 and 10 years.

Conclusion Intraoperative cardiac arrest cases must be studied more to create better management of the victims and improve the outcomes. Underestimated events in the operating room will probably end with unintended consequences. Even though some hospitals provide good standards of organizational preparation for emergencies, our survey showed that this is not the case and is not standard everywhere. Well-equipped institutes and highly trained staff may improve both technical and non-technical skills for CPR.

Keywords

Introduction

Cardiac arrest in the operating room (OR) is rare but the worst event during anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiologists who are familiar with the patient’s medical history and risks of the ongoing surgery mainly witness intraoperative cardiac arrest (IOCA). These key differences should be associated with better outcomes compared with out-of-hospital or unwitnessed in-hospital cardiac arrests.1,2

There is limited evidence to guide the management of IOCA specifically, but some recommendations for intraoperative critical events are available.1,2,3,4 Unexpected critical events in the OR can compromise patient safety or turn out to be life-threatening if appropriate teamwork, equipment, protocols, and help are not readily available. Regular training should be performed to evaluate practices and improvements.5

As in any other setting, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and advanced life support (ALS) have to be initiated as soon as cardiac arrest is recognized. This includes the performance of efficient chest compressions, ensuring ventilation, and defibrillation as rapidly as possible if ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia is present.1,2,3,4,6 Delays of more than 2 minutes in the initiation of CPR with chest compressions or defibrillation and epinephrine use have each been associated with lower survival after witnessing in-hospital cardiac arrest.7,8

Due to the experienced team in the OR and adequate equipment, it is expected that early and effective CPR should be provided in case of IOCA. However, different hospitals may have different facilities and implementations. In this survey study, we aimed to determine the presence of adequate equipment and management of intraoperative cardiac arrest in Türkiye.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a web-based survey among Turkish Society of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation members. The questionnaire was developed based on literature and contributions by CPR experts. We created our short-form questionnaire focused on CPR practices and facilities of participants and hospitals, general hospital characteristics, and pre-, peri- and post-resuscitation care. The survey consisted of 37 closed-answer questions.

We used dichotomous, multiple-choice, or multiple-response questions for each item. This nationwide survey samples resuscitation practices to provide insights into the availability of resuscitation equipment and protocols in the OR and remote anesthesia places at the institutes. With the approval of the Turkish association, the survey was shared with anesthesiology assistants and specialists working in different clinics in our country (see Supplementary Table 1). The study was conducted over three months in 2022. An invitation was sent to members with a registered e-mail. To minimize the risk of duplication of surveys being completed, each survey contained a unique link. All survey questions had to be completed to submit the survey. Respondents were asked to fill out the survey for each hospital location with inpatient care facilities within their organization. Answers were considered as consent to participate and handled anonymously. All the feedback and answers to the survey questions were statistically analyzed and recorded.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University (Date: 2022-04-16, No: E-10840098-772.02-2374).

Statistical Analysis

Participant responses were analyzed by categorizing them based on the type of institution where the participating physicians were employed. Ordinal data were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, while frequency data were assessed with the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Acquired p-values underwent multiple comparison corrections using the Benjamini-Hochberg method, with a false discovery rate set at 10%. For post-hoc analysis of responses exhibiting statistically significant differences between institutions, the Mann-Whitney-U test and Bonferroni correction were applied to ordinal data. Frequency data post-hoc analysis was conducted by considering adjusted standardized residual values smaller than -2 and bigger than 2 as significant. All statistical evaluations were made using IBM SPSS Statistics V26 Software.

The survey questionnaire is provided as Supplementary Table 1.

Reporting Guidelines

This study is reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines.

Results

A total of 252 participants completed the survey. The demographic data showed that 138 participants worked in public universities, 31 in private universities, 54 in public hospitals, and 29 in private hospitals. Most respondents were with >10 years of experience (59.5%) and practiced at academic centers (67.1%).

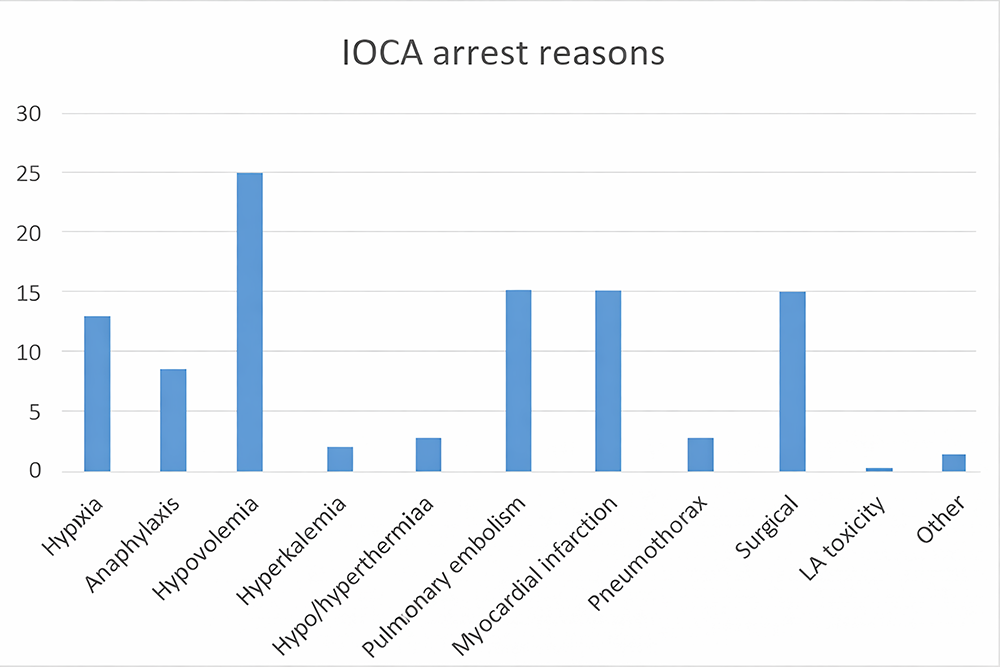

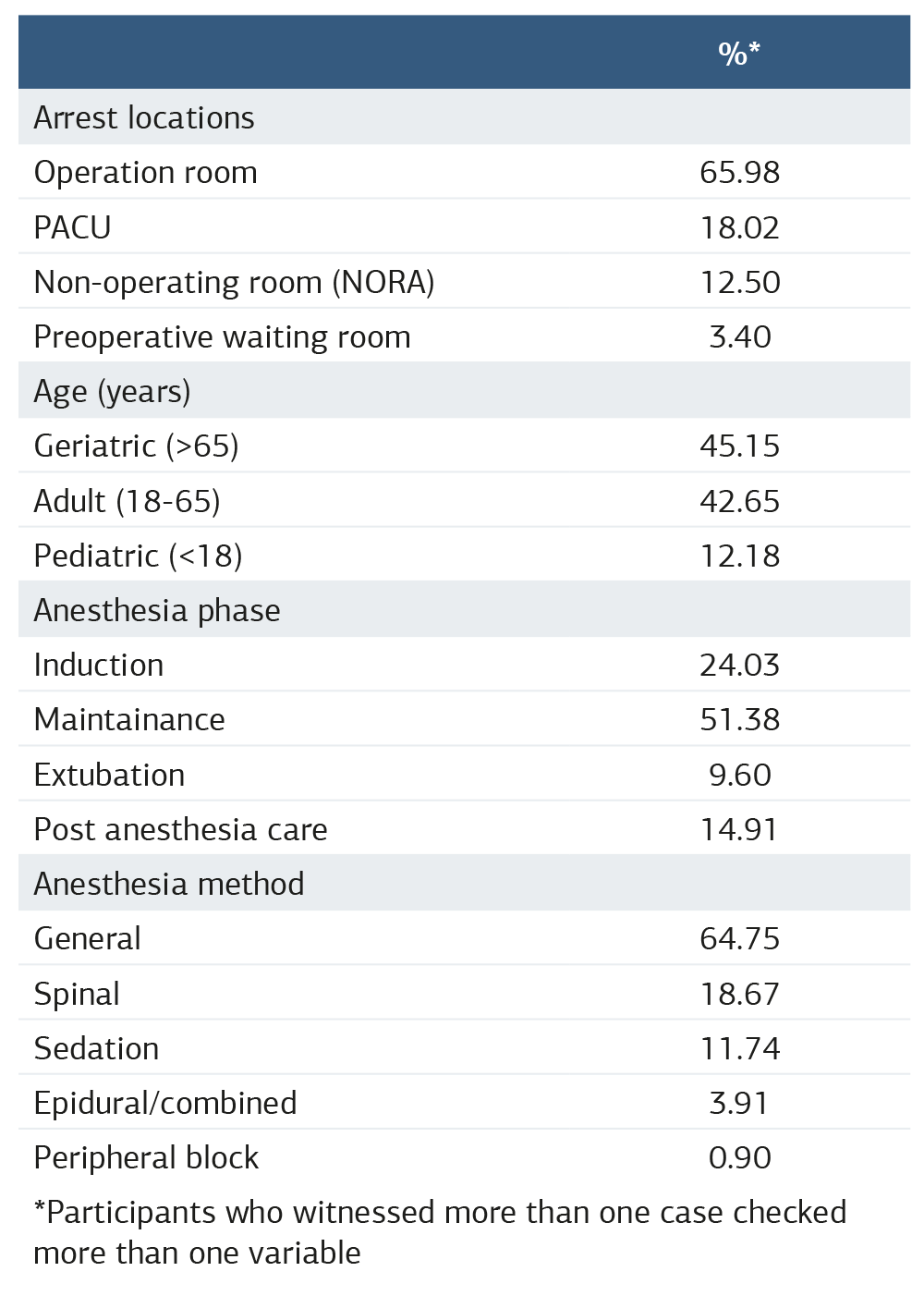

IOCA Demography: During their professional careers, 202 (80%) participants had witnessed more than one cardiac arrest, 39 (15%) had seen one, and 11 (4.4%) had never seen any. In the past year, 95 participants (37.7%) had witnessed more than one cardiac arrest, 94 (37.3%) had not seen any, and 63 (25%) had seen one. The distribution of arrest locations, patients’ age groups, anesthesia phases, and methods are shown in Table 1. The most common IOCA reasons were hypovolemia, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and others, as seen in Figure 1. Results of the resuscitations had a mortality rate of 55.6%, in which 27.08% were immediately in the operating room.

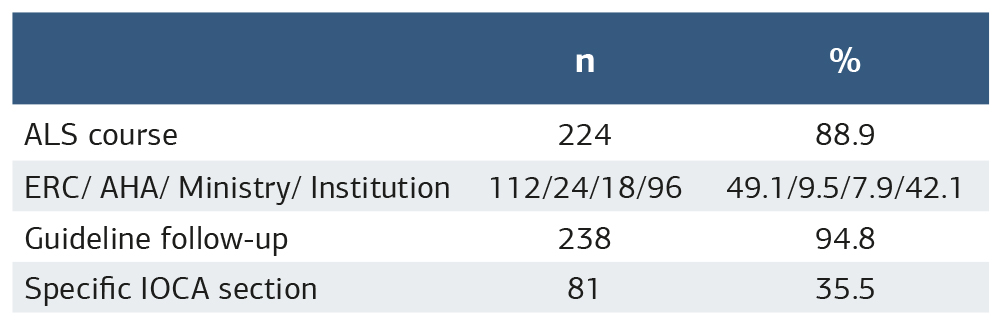

Education and Training Provision: In terms of education and training about ALS, out of 252 participants, 224 (88.9%) reported that they received ALS education. Education source types were European Resuscitation Council Advanced Life Support (ERC ALS) Courses at 44.4%, local institutional at 42.1%, and 7.9% from the Health Ministry. Among these educated participants, only 32.9% got a specific chapter about intraoperative cardiac arrest. Nevertheless, the post-hoc analysis revealed that participants who underwent CPR training from ERC Courses were statistically more likely to learn about IOCA, with 49.1% of ERC-trained participants covering this topic. Conversely, participants who received CPR training within their institutions were statistically less likely to learn about intraoperative arrest (Table 2).

Ratio for the follow-up of ALS guidelines was 94.8%. The time elapsed since the last ALS training showed no significant differences between participants. Sixty-eight physicians (29.8%) received the training in less than one year, 108 (47.4%) in between 1 and 5 years and 52 (22.8%) in between 5 and 10 years.

Facilities and Quality Improvement Actions of Hospitals

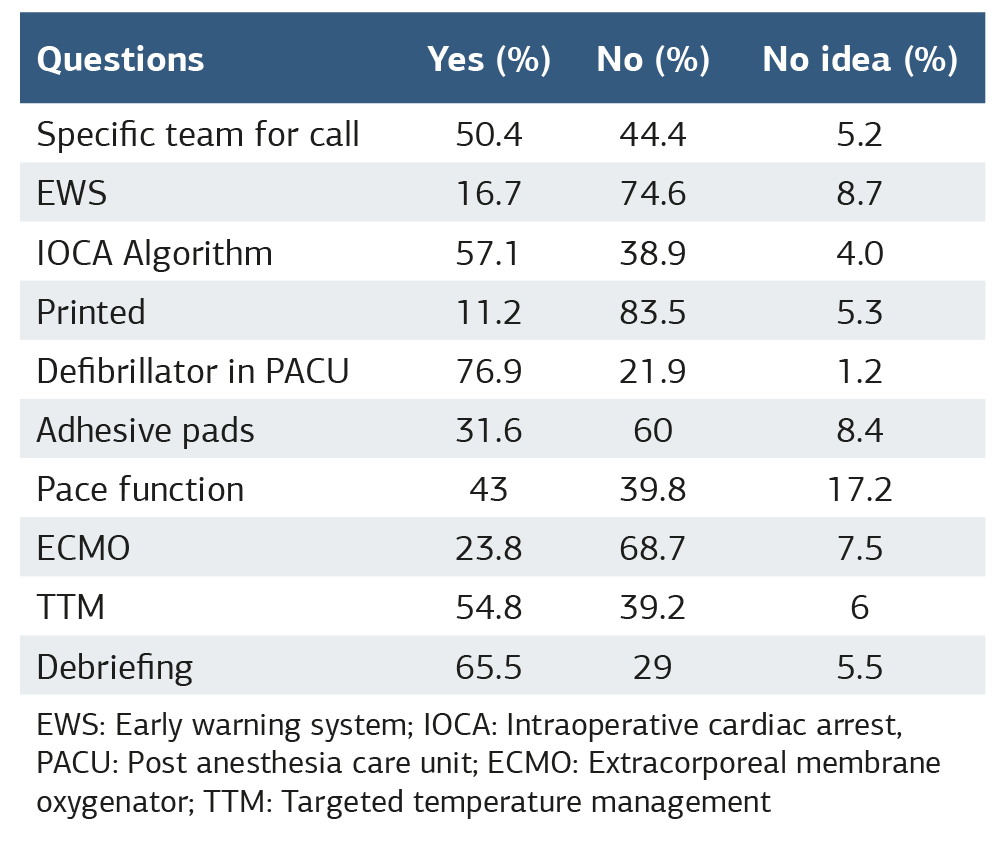

Answers to the questions below about the hospitals’ facilities among the participants were indicated in Table 3.

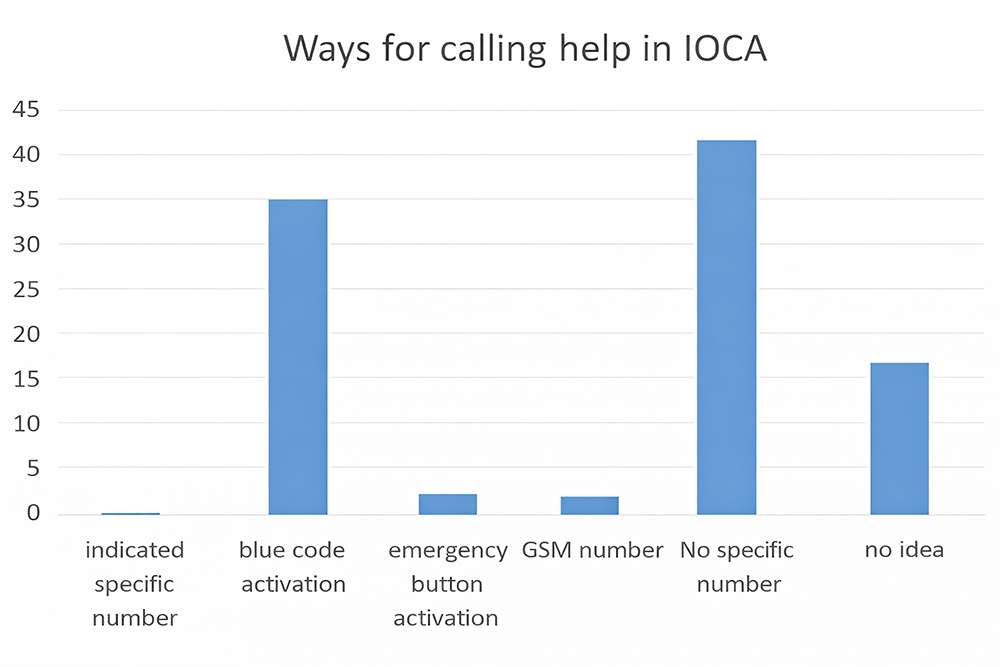

• Is there a specific phone number or call method to contact this person or team? (Figure 2).

• Is there a designated person or team to call in case of intraoperative arrest at your institution? The team leader was designated to be the anesthesiologist by all of the participants.

• Do you have an early warning system in the operating room?

• Do you use a specific intraoperative arrest algorithm?

• Are these algorithms available as printed guidelines in the operating room?

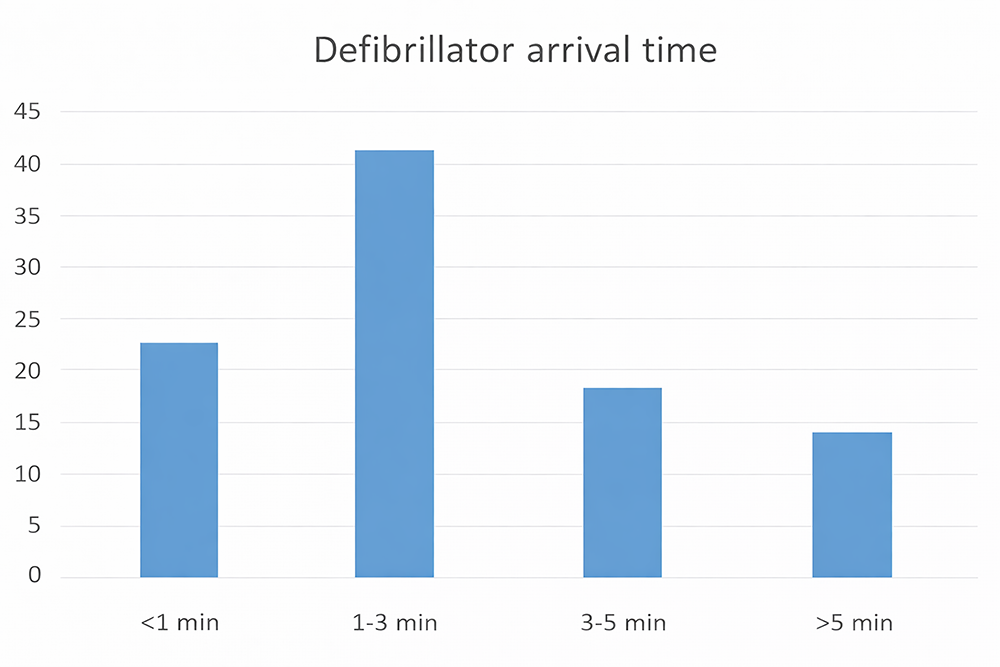

• Is there a defibrillator available in the recovery room? The time intervals for the places where defibrillators are transferred from another unit beside the victim were designated in Figure 3.

• Do the defibrillators in your area of use have a pacer application feature and adhesive pads?

• Does your hospital provide an ECMO opportunity for the appropriate arrest victims?

• Can you perform targeted temperature management (TTM) in ICU?

• Do you prefer to use debriefing to educate staff and improve resuscitation skills?

Discussion

Intraoperative cardiac arrest cases are rare, and they have quite a large spectrum of causes. The incidence of IOCA differs from 4.3 to 34.6 cases in 10000.9 Since it is very rarely seen, it has not been studied to the same extent as general cardiac arrest cases. The standardization of the clinics’ approaches and facilities in intraoperative cardiac arrest cases has not yet achieved the importance it deserves. Although general incidence rates seem very low, when we look at the demographic results of our survey, it is seen that the number of clinicians who have not experienced IOCA throughout their careers is quite low (4.4%). Another important point about the clinical importance of IOCA cases is that these cases are potentially life-limiting events, and they have mortality rates of more than 50% in the literature.6,10,11 In our survey, there was a mortality rate of 55.6%, of which 27.08% were immediately in the operating room. Such events are primarily unforgettable for the anesthetist, so even these rough results are similar to rates in the literature.

Kursumovic et al. indicated in their study that high-risk procedures are also commonly performed in the radiology department and cardiac catheterization laboratories. In our survey, the ratio of cardiac arrests in NORA was found to be 12.5%. Several difficulties, including an unfamiliar environment and challenging patients who are critically ill and need general anesthesia, increase the risk of mortality in such areas.12 Such risky NORA cardiac arrest cases might end with unintended results more than the ones in the operating rooms. The most common causes for both operating and non-operating area arrest cases in the survey were hypovolemia, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction, which are all present in the list of reversible causes (4Hs and 4Ts) in the ALS algorithm.

Moitra et al. suggested that an adopted ALS algorithm might be insufficient in the operating rooms,1 so operating room cardiac arrest cases may need their protocols and troubleshooting checklists. Until now, management recommendations were based on opinions and routine ALS protocols. In 2018, a clinical reasoning algorithm for different situations was published in the USA.1,2,4 However, it was apparent that an evidence-based guideline for IOCA management was needed.10 Thus, the 2021 ERC guideline included a specific intraoperative cardiac arrest topic under the special circumstances chapter.9 Just recently, Hinkelbein et al. published a proper guideline for IOCA.6 Thus, this and the others about this topic fill this vast gap.

Even though most respondents had at least ten years of experience and practiced at academic centers, variations were present, starting from the ALS education types to the opportunities for improvement of resuscitations. In this survey study, 88.9% of the clinicians reported that they received ALS education. Fortunately, the ratio for the follow-up of ALS guidelines was found to be 94.8% among the participants. Only 29.8% of the participants received the training in less than one year. It is indicated that there is a significant loss of knowledge and skills in ALS management if not used frequently only after six months following training. Training updates are essential, and if possible, a good standard update should be performed through ALS course repetitions. Since repeating the course is difficult in practice, reminder training courses and simulations can be provided institutionally. Among the educated participants, only 32.9% got a specific chapter about intraoperative cardiac arrest. Most of the ALS courses do not include IOCA separately. It would be ideal if anesthesiologists and surgeons took special IOCA management courses, including E-CPR simulation practice.

Considering the facilities and quality improvement actions of hospitals, it was clearly shown that different hospitals have different facilities, implementations, and protocols. Teamwork and code team leadership are very important tricks for CPR,13 and all of the participants indicated that the team leader is an anesthesiologist in any hospital. In case the anesthesiologist in the OR may be the only ALS-educated person, or he/she may be inexperienced, an emergency help call button or telephone number should be determined. Only 50.4% of the participants indicated that there is a specific team for IOCA, and unfortunately, only 38.09% had a specific call number. A special and fast-calling method should be determined for IOCA in any institute. The first step to managing such a chaotic event is to call for help, but with a specific number of qualified personnel to avoid extra confusion.14,15

Another critical point is to predict that the patient might live in an arrest condition for a while and call for help before things get worse. Several hospitals use early warning scoring systems (EWSS) inwards; however, using EWSS is quite uncommon in the operating room. Only 16.7% of the participants indicated that they use EWSS in their ORs. Many kinds of signs, such as tachycardia, bradycardia, hypoxia, hypotension, etc., may be warning signs of impending danger. Therefore, EWSS might be a good idea for prevention, and as always, preventive medicine is easier than management treatment.

There should be an algorithm, checklist, or protocol specifically designated for IOCA to increase the quality of CPR in OR. Unfortunately, only 57.1% of participants indicated that they have an intraoperative algorithm adopted from ALS guidelines, and only 11.2% of them have this algorithm printed and hung in the OR. Since stressful situations impair memory functions, the availability of prepared and printed algorithms may easily guide the chaotic period.16 Task distributions of each person and management steps should be written clearly in IOCA algorithms that were previously prepared.

The importance of immediate treatment with defibrillation for patients with shockable cardiac arrest is unquestionable.9 Defibrillation within 2 minutes after recognition of the cardiac arrest has been shown to increase survival in in-hospital cardiac arrest.8 This is the point that easily available defibrillators both in the OR and PACU would save lives after IOCA. 21.5% of the participants pointed out that they had no defibrillator in PACU. Worse than this is that 1.2% had no idea if a defibrillator was ready in PACU or not. Being foreign to the area where you are working is unacceptable.

The physicians and especially CPR team members, should recognize the area very well. Another disappointing answer about defibrillators was that 35% of the participants indicated that the time it takes for the defibrillator to reach the patient is more than 3 minutes. Delays in defibrillation decrease the survival.7,8 Resuscitation teams and institutes should improve the arrival times of defibrillators beside the victim. Every ALS provider should recognize in detail the equipment they use, especially the defibrillators. 8.8% of the participants had no idea about adhesive pads, and 17.7% had no idea about the pacing ability of their defibrillators. Some defibrillators have adhesive pads and pacing features, and some do not. However, the point is to know about the features of devices.

The most critical and challenging facility of a hospital for prolonged CPR is the availability of E-CPR, in other words, extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO). Only 25.4% of participants indicated that they could perform ECMO in their institutes. Performing an ECMO requires not only expensive devices but also an experienced team working on E-CPR. Not all healthcare systems have sufficient management resources.

Finally, a data-driven performance focused on debriefing after CPR has been shown to improve the quality and prognosis of resuscitation. In this survey, debriefing rates were found to be considerably high (66.9%).5,9 Debriefing meetings and simulation training can improve team dynamics, experiences, and working qualities.

Limitations

There are some limitations in this study. Participation in the survey was not as high as we expected, and most of the participants were those who had participated in some courses and were interested in this topic. Therefore, the actual rate of anesthetists who are educated about intraoperative cardiac arrest may be much lower. Even though this picture is a little flue, it gives clues about problems for cardiac arrest in the OR or areas where anesthesia is given in our country.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IOCA must be studied more to create better management of the victims and improve the outcomes. Underestimated events in the operating room will probably end with sad, unintended consequences. Even though some hospitals provide good standards of organizational preparation for emergencies, including cardiac arrest, our survey showed that this is not the case and is not standard everywhere. A successful ALS during surgery and beyond needs anticipation, early recognition, teamwork, and organized treatment steps. Well-equipped institutes and highly trained staff may improve both technical and non-technical skills for CPR.

Figures

Figure 1. Intraoperative cardiac arrest reasons (%). LA: local anesthesics

Figure 2. Indicated ways for calling help (%)

Figure 3. The time intervals for the places where defibrillators were transferred from another unit beside the victim. (% in y-axis)

Tables

Table 1. Intraoperative arrest variables

*Participants who witnessed more than one case checked more than one variable

Table 2. Advanced life support (ALS) education

Table 3. Facilities of the hospitals among participants

EWS: Early warning system; IOCA: Intraoperative cardiac arrest, PACU: Post anesthesia care unit; ECMO: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator; TTM: Targeted temperature management

References

-

Moitra VK, Einav S, Thies KC, et al. Cardiac arrest in the operating room: resuscitation and management for the anesthesiologist: part 1. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):876-888.

-

McEvoy MD, Thies KC, Einav S, et al. Cardiac arrest in the operating room: part 2—special situations in the perioperative period. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):889-903.

-

Hinkelbein J, Andres J, Thies KC, De Robertis E. Perioperative cardiac arrest in the operating room environment: a review of the literature. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(11):1190-1198.

-

Chalkias A, Mentzelopoulos SD, Tissier R, Mongardon N. Peri-operative cardiac arrest and resuscitation: towards an innovative, physiologically based road map. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2024;41(5):393-396.

-

Nair A, Naik V, Rayani BK. Perioperative cardiac arrest: teamwork and management. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care.2016;20(Suppl):S97-S105.

-

Hinkelbein J, Andres J, Böttiger BW, et al. Cardiac arrest in the perioperative period: a consensus guideline for identification, treatment, and prevention from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care and the European Society for Trauma and Emergency Surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2023;40(10):724-736.

-

Mhyre JM, Ramachandran SK, Kheterpal S, Morris M, Chan PS. Delayed time to defibrillation after intraoperative and periprocedural cardiac arrest. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(4):782-793.

-

Bircher NG, Chan PS, Xu Y. Delays in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, defibrillation, and epinephrine administration all decrease survival in in-hospital cardiac arrest. Anesthesiology. 2019;130(3):414-422.

-

Soar J, Böttiger BW, Carli P, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:115-151. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.010

-

Hinkelbein J, Böttiger BW. Intraoperative cardiac arrest: of utmost importance and a stepchild at the same time. Anesth Analg. 2020;130(3):625-626.

-

Truhlar A, Deakin CD, Soar J, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015;95:148-201.

-

Kursumovic E, Soar J, Nolan JP. Organization of UK hospitals and anaesthetic departments in the treatment of peri-operative cardiac arrest: an analysis from the 7th National Audit Project (NAP7) local co-ordinator baseline survey. Anaesthesia. 2023;78(12):1442-1452.

-

Cahn J. Intraoperative cardiopulmonary arrest. AORN J. 2022;116(5):450-459.

-

Cusma PR. Intraoperative cardiac arrest: literature review and new tool to patient’s and team’s safety. Arch Emerg Med Crit Care. 2016;1(2):1008.

-

Tallman K, Ramachandran SK, Christensen R, O’Brien D. Cardiac arrest in the PACU: an analysis of evolving challenges for perianesthesia nursing. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26(1):4-8.

-

Fioratou E, Flin R, Glavin R. No simple fix for fixation errors: cognitive processes and their clinical applications. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(1):61-69.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University (Date: 2022-04-16, No: E-10840098-772.02-2374)

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The corresponding author has committed to share the de-identified data with qualified researchers after confirmation of the necessary ethical or institutional approvals. Requests for data access should be directed to bmp.eqco@gmail.com

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.K., P.K.

Methodology: B.K., P.K.

Data Collection: M.S.Ş., H.B.

Statistical Analysis: A.Y.

Writing – Original Draft: B.K.

Writing – Review & Editing: All authors

Abbreviations

AHA: American Heart Association

ALS: Advanced Life Support

CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

ECMO: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenator

ECPR: Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

ERC: European Resuscitation Council

EWS: Early Warning System

EWSS: Early Warning Scoring System

ICU: Intensive Care Unit

IOCA: Intraoperative Cardiac Arrest

LA: Local Anesthetics

NORA: Non-Operating Room Anesthesia

OR: Operating Room

PACU: Post Anesthesia Care Unit

TTM: Targeted Temperature Management

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Bahar Kuvaki, Pelin Karaaslan, Muhammet Selman Söğüt, Handan Birbiçer, Yeşim Andıran Şenaylı, Aysun Ankay Yılbaş. Institutional preparedness and management of intraoperative cardiac arrest: a survey. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(Suppl 1):S7-11

Publication History

- Received:

- January 2, 2025

- Accepted:

- May 5, 2025

- Published Online:

- May 16, 2025

- Printed:

- February 20, 2026