Evaluation of halp score and inflammatory markers in patients with diabetic retinopathy

Halp results in drp

Authors

Abstract

Aim In this study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between HALP score, a new systemic inflammatory marker, and diabetic retinopathy (DRP) and compare it with other systemic inflammatory markers.

Methods In this retrospective study, 357 diabetic patients who applied to the Aksaray University Education and Research Hospital Retina Polyclinic between 2022 and 2024 were evaluated. Patients were evaluated in 3 groups in terms of the absence of DRP (n=127), presence of DRP (n=164) and presence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (n=66). Neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, monocytes and albumin levels of the patients were used to calculate systemic inflammation markers. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), systemic inflammatory index (SII), systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), pan-immune inflammation value (PIV) and HALP scores of all groups were calculated.

Results Significant differences were observed in HALP scores and other systemic inflammatory markers with the development and progression of DRP (p<0.001). In our study, it was observed that lower HALP scores were associated with DRP (p<0.001) and HALP scores below 4.45 were an important cutoff value for the development of proliferative DRP with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.812 and a sensitivity and specificity of 71%.

Conclusion HALP score is a significant marker in terms of DRP and DRP progression in the follow-up of diabetic patients. We think that it is a valuable marker

for creating awareness among clinicians in the follow-up and treatment of the patient

Keywords

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DRP) is the most common ocular complication affecting around one-third of individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) and serving as a major contributor to vision impairment in adults 1. According to data from the World Health Organization, DRP is estimated to account for 4.8% of blindness in adults 2. In recent decades, the prevalence of DRP has risen, imposing considerable strain on healthcare systems and economic resources 3. Early detection of DM, effective medical management, and timely interventions are crucial in preventing the onset of DRP 4. Persistent hyperglycemia- induced inflammation in the retina leads to leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells, increased vascular permeability, migration of leukocytes and monocytes, and the release of enzymes, cytokines, growth factors, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), ultimately causing endothelial damage 5,6,7. Activated platelets promote vascular obstruction by forming thrombi with red blood cells through the secretion of mediators. Retinal ischemia and hypoxia further drive inflammatory cell infiltration, ROS production, and angiogenic growth factor release 8. Chronic ischemia disrupts the angiogenic equilibrium in the retina, triggering neovascularization. Loss of perivascular cells, microaneurysms, capillary dilation and occlusion, and damage to the blood-retinal barrier lead to fluid accumulation within retinal layers, causing to diabetic macular edema (DME). Thus, prolonged hyperglycemia and inflammation exacerbate DRP and DME, causing irreversible visual impairment.

Various markers that assess systemic inflammation, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), pan-immune inflammation value (PIV), systemic inflammatoryindex (SII), and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), are used to evaluate the prognosis and treatment outcomes of systemic and ocular diseases 9,10,11.

Several studies have explored the relationship between systemic inflammatory markers such as NLR, SII, and SIRI and with DRP in diabetic individuals, revealing significant correlations between these markers, retinopathy, and macular edema 12,13,14.

The hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score, derived from complete blood count parameters and albumin levels, has recently emerged as a novel inflammatory marker. Recent investigations have also identified the HALP score as a significant biomarker in pseudoexfoliation syndrome and glaucoma associated with systemic inflammation, highlighting its role in glaucoma progression 15. Current research is focused on the association between the HALP score and DRP. This study aims to investigate the relationship between the HALP score and DRP while comparing it with other systemic inflammatory markers.

Materials and Methods

The medical records of 357 diabetic patients aged 40 to 90 years, who visited the Retina Clinic at Aksaray University Training and Research Hospital between November 2022 and January 2024, were reviewed retrospectively. The medical records of the patients who applied within the last month were evaluated.

Individuals with chronic renal failure, type 1 diabetes, poorly controlled hypertension, malignancy, immunosuppression, rheumatological disorders, or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy were excluded. Additionally, patients with acute or chronic systemic infections and other inflammatory diseases were not included. Patients included in the study during the retrospective file scan are those who have had recent hemogram and albumin tests. The medications used by the patients were recorded (Table 1). All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Clinical evaluations included fundus examinations, optical coherence tomography (OCT) (AVANTI® (Optovue, Inc, Fremont, California, USA)), and either color fundus photography or fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) (VISUCAM® 524 (ZEISS, Jena, Germany)). Retinopathy staging followed the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) group criteria, and diabetic macular edema was recorded 16. Patients’ demographic information, duration of diabetes, medication usage, and clinical test results, including complete blood counts, biochemistry, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), were documented. Systemic inflammatory markers were calculated using the following formulas: Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) = neutrophil (/L) / lymphocyte (/L), Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) = platelet (/L) / lymphocyte (/L), Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI) = neutrophil (/L) × monocyte (/L) / lymphocyte (/L), Pan-Immune Inflammation Value (PIV) = neutrophil (/L) × monocyte (/L) × platelet (/L) / lymphocyte (/L), Systemic Inflammatory Index (SII) = neutrophil (/L) × lymphocyte (/L) / platelet (/L), and Hemoglobin Albumin Lymphocyte Platelet (HALP) score = hemoglobin (g/L) × albumin (g/L) × lymphocyte (/L) / platelet (/L).

The patients were categorized into three groups based on their retinopathy status: Group 1 (NDRP) consisted of 127 patients (35.5%) with no retinopathy, Group 2 (NPDRP) included 164 patients (45.9%) with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and Group 3 (PDRP) comprised 66 patients (18.5%) with proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 26 (IBM Corp., 2019). The Kolmogorov- Smirnov test assessed parameter distribution. Parametric data were expressed as mean and standard deviation, while non- parametric data were summarized as medians with minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Parametric data were analyzed using the one-way ANOVA test, whereas non- parametric data were evaluated with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Posthoc comparisons among groups were conducted using the Bonferroni method. Differences in macular edema and systemic inflammatory markers were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to assess the sensitivity and specificity of systemic inflammatory biomarkers (SIBs), and optimal cutoff values for predicting proliferative retinopathy were identified and compared.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Aksaray University (Date: 2023-09-28, No: 2023/18-01).

Results

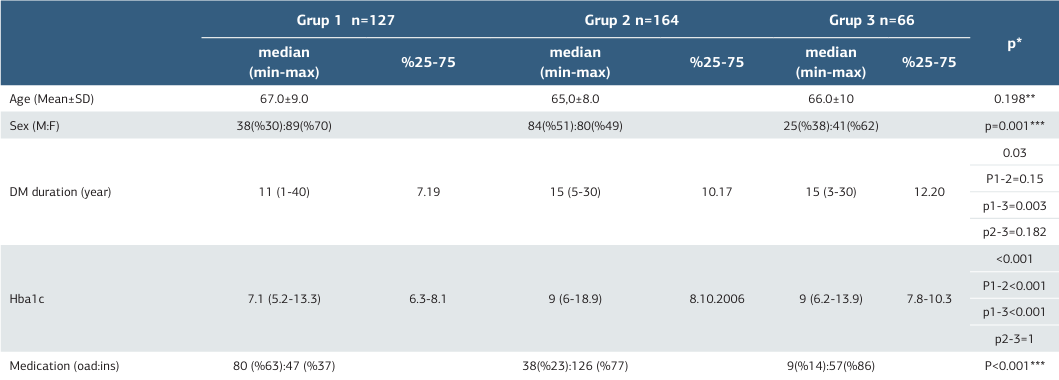

The demographic characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. The average ages of the groups were 67±9 years (Group 1), 65±8 years (Group 2), and 66±10 years (Group 3), with no significant intergroup variation (p=0.19). Median diabetes duration (25-75%) was observed as 11 (7-19) in Group 1, 15 (10-17) in Group 2, 15 (12-20) in Group 3 and there was a significant difference between the groups (p=0.03). Median Hba1c values (25-75%) were observed as 7.1 (6.3-8.1) in Group 1, 9 (8-10.6) in Group 3 and there was a significant difference between the groups (p<0.0001).

Demographic details, including age, gender, diabetes duration, HbA1c, and medication use, are detailed in Table 1.

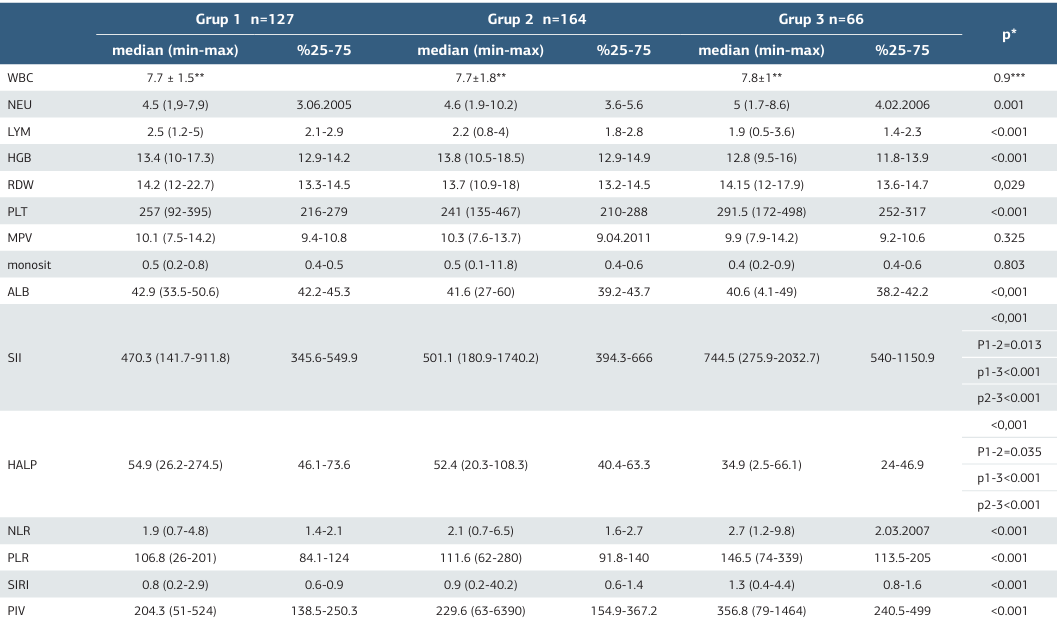

Analysis of hematological and biochemical parameters showed no significant differences in white blood cell count, monocyte levels, or mean platelet volume (MPV) across the three groups (p=0.9, p=0.325, p=0.803 respectively). However, neutrophil and platelet counts were significantly higher in the PDRP group (p=0.001, p<0.001), while lymphocyte counts and albumin levels were markedly lower (p<0.001).

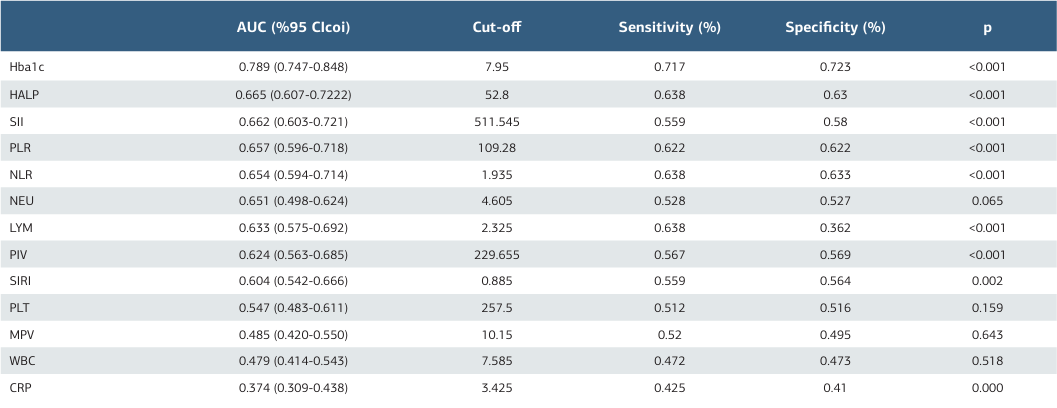

When systemic inflammatory biomarkers (SIBs) were evaluated, significant differences were observed in NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, and PIV values across the groups (p<0.001, Table 2). Median SII values increased progressively with retinopathy severity: 470 in Group 1, 501 in Group 2, and 744 in Group 3 (p<0.001). Subgroup comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed significant differences between all groups (p1-2=0.013, p1- 3<0.001, p2-3<0.001 respectively). HALP scores showed a progressive decrease, with median values of 54.9, 52.4, and 34.9 in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Differences between all groups were statistically significant (p1-2=0.035, p1-3<0.001, p2-3<0.001respectively). Macular edema was observed in 200 patients (56%), while 157 patients (44%) showed no signs of edema. Comparisons of SIBs based on the presence of macular edema revealed significant differences in HALP, SII, NLR, and PLR values. The median HALP value was 53.0 in patients without macular edema and 48.8 in those with edema, with significantly lower values in the latter group (p=0.007). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to assess SIBs for DRP with results shown in Tables 3. HALP and SII markers demonstrated the highest area under the curve (AUC) values for both DRP and PDRP development. For DRP, the HALP AUC value was 0.665 (cutoff: 52.8, sensitivity: 63.8%, specificity: 63%), while for PDRP, the AUC increased to 0.812 (cutoff: 44.5, sensitivity: 71%, specificity: 71%), indicating a lower cutoff point in proliferative stages. SII, PLR, PIV, NLR, and SIRI markers also showed high AUC values, though with a decreasing trend.

Discussion

Diabetic retinopathy (DRP) is a leading cause of severe vision impairment in adults. Proper and consistent diabetes management is crucial to prevent vision loss in diabetic patients. In cases where diabetes is poorly controlled, both hyperglycemia and inflammation significantly contribute to the progression of DRP. Therefore, monitoring inflammatory responses is essential to mitigate the risk of vision loss.

The connection between inflammatory responses and DRP is well-established. Kocabora et al. reported increased aqueous humor TNF-α and serum CRP levels in diabetic macular edema (DME) patients 17. Similarly, Sonoda et al. found heightened intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), IL-6, and IL-8 levels in DME patients 18,19. However, analyzing inflammatory markers in aqueous humor or vitreous samples is invasive, costly, and complex. This has led researchers to focus on peripheral blood-based inflammatory markers. Doğanay et al. observed elevated serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, sIL-2R, IL-6, IL-8, and nitric oxide in DME patients 20, and several studies have confirmed increased serum levels of CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 in DRP patients 21.

Over time, simpler, less invasive, and cost-efficient methods to assess systemic inflammation have emerged. For instance, systemic inflammatory biomarkers (SIBs) such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune- inflammation index (SII), and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) are now calculated from routine blood tests. Woo et al. demonstrated elevated NLR in DRP patients, while Ulu et al. reported an association between NLR and DRP progression 22,23. İlhan et al. identified a cutoff NLR value of 2.26 for DME patients, with 85% sensitivity and 74% specificity 21. In our research, the NLR cutoff was 2.13, with 63% sensitivity and specificity, while the PLR cutoff was 124, achieving 70% sensitivity and specificity. These findings align with previous studies. Wang et al. reported increased SII and SIRI values in DRP patients, while Elbeyli et al. observed higher SII in DME patients 13,24. Our study found an SII cutoff of 578.6, with 71% sensitivity and specificity, which is consistent with prior findings.

Unlike other inflammatory markers, HALP considers both inflammation and nutritional status and is particularly valuable as a prognostic tool several diseases 25 . HALP has been associated with lower levels in ocular conditions such as pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma 15. Our study showed that lower HALP scores were associated with DRP progression (p<0.001), with a cutoff of 44.5 for predicting PDRP, yielding 71% sensitivity and specificity.

Clinicians commonly use SIBs to evaluate systemic inflammation in DME patients. Inflammatory processes driven by hyperglycemia result in microvascular damage, capillary thrombosis, ischemia, and tissue hypoxia, all of which contribute to DRP pathogenesis. Hypoxia in the retina, where blood flow is compromised, underscores the importance of hemoglobin levels. Consequently, the HALP score, which includes hemoglobin alongside other inflammatory parameters, may more accurately reflect systemic inflammation in diabetic patients than other markers. Our research identified HALP as the most effective marker in ROC analysis for DRP and PDRP prediction.

Ding et al. using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), demonstrated reduced HALP scores in DRP patients (NDRP 50.67 ± 1.11 vs. DRP 56.14 ± 0.93, p<0.001), though DRP was self-reported rather than confirmed via medical records. Similarly, Wang et al. observed lower HALP scores in DRP patients (NDRP 50.32 vs. DRP 43.83, p<0.001), with an AUC of 0.63 and sensitivities and specificities of 55.6% and 63.4%, respectively. Unlike these studies, our work classified DRP stages and found more significant decreases in HALP scores in PDRP patients. For DRP, the HALP AUC was 0.665 (cutoff: 52.8, sensitivity: 63.8%, specificity: 63%), while for PDRP, it increased to 0.812 (cutoff: 44.5, sensitivity: 71%, specificity: 71%). Additionally, we compared HALP with other SIBs, providing a broader perspective on its relationship with DRP.

Our study confirmed a significant link between elevated HbA1c levels and DRP progression (p<0.001). The HbA1c AUC was 0.789 (cutoff: 7.95, sensitivity: 71.7%, specificity: 72.3%) for DRP, but this value decreased for PDRP (AUC 0.639, cutoff: 8.45, sensitivity: 59.6%, specificity: 59.3%). In contrast, SIBs, including HALP, demonstrated higher predictive power for PDRP progression, emphasizing the role of systemic inflammation in diabetes complications. Consequently, monitoring SIBs alongside HbA1c in DRP patients could be beneficial. Given the limited research on HALP scores and DRP, our study contributes novel insights. It is the first to demonstrate a consistent decline in HALP scores with DRP progression, particularly in PDRP cases. Moreover, this is the first study to evaluate HALP alongside NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, and PIV in DRP and PDRP patients, showing significant increases in these markers and a pronounced decrease in HALP scores.

Limitations

This was a retrospective, single center study with a limited number of patients. In our study, DME and OCT markers of DME were not compared with HALP score, but this is the subject of other studies. Randomized and controlled studies in larger patient groups are needed to elucidate the relationship between HALP score and DRP.

Conclusion

HALP score, which is an indicator of systemic inflammation in patients with DRP, decreases significantly and other SIBs increase. Our study is the first study to show that low HALP score levels are associated with retinopathy progression in diabetic patients. The HALP score, which is easy, cost-effective, and can be calculated from routine blood parameters, is a promising systemic inflammatory marker that can be used to monitor inflammatory response and progression in diabetic retinopathy patients as well as in cancer patients, and in this sense, it can be beneficial to clinicians in daily practice.

Tables

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data of the study groups

* Kruskal- Wallis ,** One -Way Anova, *** Pearson’s Chi Square DM:Diabetes Mellitus; Oad: oral anti diabetic; İns: insülin

Table 2. Comparison of the blood parameters of the study and control groups

* Kruskal- Wallis, ** Mean and standart deviation, *** One -Way Anova Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR), Systemic Inflammatory Index (SII), Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI), Pan-Immune Inflammation Value (PIV)

Table 3. ROC analysis values of systemic inflammatory markers according to the presence of diabetic retinopathy

References

-

Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556-64.

-

Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):844-51.

-

Tan TE, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy: Looking forward to 2030. Front Endocrinol. 2023;(13):1077669.

-

Ockrim Z, Yorston D. Managing diabetic retinopathy. BMJ. 2010;341:c5400.

-

Stitt AW, Curtis TM, Chen M, et al. The progress in understanding and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;51:156-86.

-

Tang J, Kern TS. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30(5):343-58.

-

Valle A, Giamporcaro GM, Scavini M, et al. Reduction of circulating neutrophils precedes and accompanies type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62(6):2072-7.

-

Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(22):1480.

-

Yağcı BA, Erdal H. Can pan-immune inflammation value and systemic inflammatory response index be used clinically to predict inflammation in patients with cataract. Ann Clin Anal Med. 2023;14(12):1064-7.

-

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5 Suppl):786-806.

-

Kazan DE, Kazan S. Systemic immune inflammation index and pan-immune inflammation value as prognostic markers in patients with idiopathic low and moderate risk membranous nephropathy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(2):642-8.

-

İhan C, Citirik M, Uzel MM, Kiziltoprak H, Tekin K. The usefulness of systemic inflammatory markers as diagnostic indicators of the pathogenesis of diabetic macular edema. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2020;83(4):299-304.

-

Wang S, Pan X, Jia B, Chen S. Exploring the correlation between the systemic immune inflammation index (SII), systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), and type 2 diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;(16):3827-36.

-

Tetikoğlu M, Aktas S, Sagdık HM, Tasdemir Yigitoglu S, Özcura F. Mean platelet volume is associated with diabetic macular edema in patients with type- 2 diabetes mellitus. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017;32(5):651-4.

-

Akbulut Yagci B, Erdal H. Can the halp score, a new prognostic tool, predict the progression of pseudoexfoliation patients to pseudoexfoliation glaucoma? Ann Clin Anal Med. 2025;16(4):272-5.

-

Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs-- an extension of the modified Airlie House classification. ETDRS report number 10. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5):786-806.

-

Kocabora MS, Telli ME, Fazil K, et al. Serum and aqueous concentrations of inflammatory markers in diabetic macular edema. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(5):549-54.

-

Sonoda S, Sakamoto T, Shirasawa M, Yamashita T, Otsuka H, Terasaki H. Correlation between reflectivity of subretinal fluid in OCT images and concentration of intravitreal VEGF in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(8):5367-74.

-

Sonoda S, Sakamoto T, Yamashita T, Shirasawa M, Otsuka H, Sonoda Y. Retinal morphologic changes and concentrations of cytokines in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Retina. 2014;34(4):741-8.

-

Doganay S, Evereklioglu C, Er H, et al. Comparison of serum NO, TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, sIL-2R, IL-6 and IL-8 levels with grades of retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eye (Lond). 2002;16(2):163-70.

-

Gouliopoulos NS, Kalogeropoulos C, Lavaris A, et al. Association of serum inflammatory markers and diabetic retinopathy: A review of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(21):7113-28.

-

Woo SJ, Ahn SJ, Ahn J, Park KH, Lee K. Elevated systemic neutrophil count in diabetic retinopathy and diabetes: A hospital-based cross-sectional study of 30,793 Korean subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(10):7697-703.

-

Ulu SM, Dogan M, Ahsen A, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a quick and reliable predictive marker to diagnose the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(11):942-7.

-

Elbeyli A, Kurtul BE, Ozcan SC, Ozarslan Ozcan D. The diagnostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in diabetic macular oedema. Clin Exp Optom. 2022;105(8):831-5.

-

Erdal H, Gunaydin F. HALP score for chronic spontaneous urticaria: Does it differ from healthy subjects? J Exp Clin Med. 2023;40(4):677-80.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Aksaray University (Date: 2023-09-28, No: 2023/18-01)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Kayhan Mutlu, Huseyin Erdal, Betul Akbulut Yagci. Evaluation of halp score and inflammatory markers in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Ann Clin Anal Med 2025;16(12):856-860

Publication History

- Received:

- January 26, 2025

- Accepted:

- March 3, 2025

- Published Online:

- April 16, 2025

- Printed:

- December 1, 2025