The effects of low tidal volume ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass on postoperative pulmonary complications

Pulmonary complications in low tidal volume ventilation

Authors

Abstract

Aim To compare the Postoperative Pulmonary Complication Scores (PPCs) and Modified Clinical Pulmonary Infection Scores (mCPIS) of patients who were either ventilated using low tidal volume or not ventilated at all during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) procedures in on-pump coronary artery graft surgeries.

Methods Demographic data including age, gender, ASA (American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification) scores, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status of the 64 patients were recorded. In Group 1, patients were ventilated with a 3-4 ml/kg tidal volume during the cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. In Group 2, 32 patients were not ventilated during cardiopulmonary bypass. PPC and mCPIS scores were evaluated at the 24th hour after intubation.

Results There was no difference between the two groups regarding demographic data (p>0.05). PPCs and mCPIS values were statistically significantly lower in Group 1 compared to Group 2, respectively (%0 / %65.6) and (%0 / %62.5) (p < 0.05). The postoperative 6th-hour blood gas PaO2 values were significantly higher in Group 1 than in Group 2, respectively (126.9 ± 24.2 mmHg/111.3 ± 26.2 mmHg) (p < 0.05). Mechanical ventilation duration (649.5 ± 153.5 / 896.4 ± 252.8 min), time to extubation (390.3 ± 136.7 / 652.2 ± 228.4 min), intensive care unit (37.5 ± 11.1 / 62.2 ± 30.2 h), and hospital (9.5 ± 2.9 / 15.7 ± 6.8 days) stays of the patients in Group 1 were statistically significantly shorter than Group 2.

Conclusion In on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery, low tidal volume ventilation applied during CPB resulted in shorter mechanical ventilation duration, time to extubation, intensive care unit, and hospital stays. It has also been shown to reduce PPCs and mCPIS when evaluated in the postoperative period.

Keywords

Introduction

Postoperative Pulmonary Complications (PPCs) are defined as postoperative pulmonary abnormalities resulting in identifiable diseases or dysfunctions that negatively impact the patient’s clinical outcome 1. PPCs manifest as atelectasis, pneumothorax, bronchospasm, pneumonia, or pleural effusion, resulting in respiratory failure and may increase postoperative mortality rates. These complications can worsen the prognosis by prolonging the duration of mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit (ICU) stay 2.

During the postoperative period, changes in pulmonary mechanics and impaired gas exchange contribute to the development of pulmonary complications, particularly after extracorporeal circulation. Various factors commonly associated with extracorporeal circulation during cardiac surgery, such as atelectasis, transfusion requirements, advanced age, heart failure, emergency surgery, and prolonged bypass time, can exacerbate the risk of pulmonary complications 3. The application of lung ventilation in cardiac surgery should be justified with the highest level of clinical evidence due to its potential impact on surgical procedures and cardiac function 4.

We aimed to compare the Postoperative Pulmonary Complication Scores (PPCs) and Modified Clinical Pulmonary Infection Scores (mCPIS) of patients who were either ventilated using low tidal volume or not ventilated at all during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) procedures in on-pump coronary artery graft surgeries. Additionally, we aimed to compare postoperative 6th-hour blood gas values, extubation times, and durations of ICU and hospital stays between the groups.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for medical research involving human subjects, published in 2013. Intraoperative and postoperative data of patients who underwent on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery between March 1, 2021, and January 12, 2022, were evaluated. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

A total of 64 patients aged 33-70 years undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery were included in the study. The study excluded patients with ejection fractions (EFs) below 40%, restrictive lung disease, liver failure, neuromuscular disease, morbid obesity, pregnancy, alcohol or drug addiction, those receiving immunosuppressive therapy or emergency surgeries and individuals with a history of thoracotomy or sternotomy. There were 32 patients in each group; Group 1 included patients ventilated with low tidal volume while Group 2 non-ventilated patients during CPB. The decision to apply ventilation during CPB was made collaboratively by the surgical and anesthesiology team, tailored to the specific intraoperative context to optimize patient outcomes. This team-based approach allowed flexibility to adjust ventilation practices based on institutional protocols, real-time clinical assessments, surgical workflow, and individual patient needs. Standard anesthesia procedures were applied to all patients. Preoperative serum albumin (g/dL), creatinine (mg/dL), hemoglobin (g/dL), and ejection fraction (%) values of the patients were recorded. In the operating room, patients were monitored with electrocardiography (ECG), non-invasive blood pressure measurements (mmHg), and peripheral oxygen saturation levels (SpO2). Peripheral venous catheterization with a 20-22 gauge catheter was performed for fluid resuscitation with 0.9% isotonic saline infused at doses of 4-5 ml/kg/h.

Patients inhaled 100% oxygen prior to induction of general anesthesia. During the induction phase of general anesthesia, patients received midazolam (0.05 mg kg-1 to 0.1 mg kg- 1), propofol (up to 2 mg kg-1), fentanyl (5-10 μg kg-1), and rocuronium (0.6 mg kg-1) via intravenous route. Radial arterial and central venous catheterizations were performed.

All patients were ventilated by using Datex-Ohmeda Avance S5 (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK) Workstation, and volume control mode (V-CMV) was adjusted to 6-8 ml/kg tidal volüme (predicted body weight) with a peak pressure not exceeding 25 cmH2O. Respiratory frequency is adjusted between 12-18 min- 1 to maintain end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) of 30-35 mmHg. Ventilation was adjusted to maintain PEEP at five mmHg, FiO2 at 40%, and I/E ratio at 1:2.

Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved with sevoflurane inhalation at a concentration of 1.5-2 %, remifentanil infusion at 0.1-0.2 μg kg -1min -1, and IV rocuronium bolus injections at doses of 0.1-0.2 mg kg-1 every 30 minutes. The partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO₂) was assessed at approximately 30-minute intervals through arterial blood gas analysis. Ventilation was discontinued in Group 2 during CPB, while in Group 1, ventilation continued with a tidal volume of 3-4 ml kg-1 (predicted body weight), frequency 12 min-1, and five cmH2O positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Midazolam, fentanyl, and rocuronium were administered via pump during CPB.

After CPB terminated, maintenance of anesthesia was achieved with 1.5-2 % sevoflurane inhalation, remifentanil infusion at 0.1-0.2 μg kg -1min-1, and IV rocuronium bolus injections every 30 minutes. Duration of surgery and CPB, fluid and blood replacement volumes, amount of blood loss, and urine outputs were recorded.

All intubated patients underwent recruitment maneuvers before leaving the operating room and were transferred to the Cardiovascular Surgery Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for close monitoring and extubation within the first postoperative 24 hours. Prior to transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), all patients were administered 1 gram of acetaminophen and intravenous tramadol at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Ventilation parameters were adjusted to maintain FiO2 > 0.4, respiratory rate < 20/min, PaO2 > 60 mmHg, PaCO2 < 45 mmHg. Specifically, ventilation parameters —such as tidal volume, respiratory rate, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)— were adjusted to optimize lung inflation and reduce atelectasis, which supports effective drainage and minimizes fluid accumulation in the chest cavity. By coordinating ventilation settings with chest tube output, we ensured that lung function and drainage were effectively balanced throughout the procedure.

Patients were extubated if they were awake, followed commands without the need for inotropes, and fulfilled the required respiratory criteria. Chest physiotherapy, cough stimulation techniques, and incentive spirometry were applied after the extubation of the patients. Arterial blood gases were measured at 6 hours after ICU admissions. All patients were administered intravenous acetaminophen every six hours for postoperative analgesia. If a patient’s Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score exceeded 3, tramadol (1 mg/kg) was administered as the initial analgesic intervention. Morphine (0.05 mg/kg) was subsequently added as needed for further pain management. Patients were evaluated based on risk scores for postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) and modified Clinical Pulmonary Infection Scores (mCPIS) estimated at 24 hours postoperatively. Postoperative chest X-rays and arterial blood gases were evaluated. PPCs were assessed for cough, increased mucus production, chest pain, dyspnea, fever (>38°C), and tachycardia (>100/min). A total score >3 out of 6 was considered positive. The modified mCPIS were assessed for tracheal secretions, chest X-ray infiltrates, temperature, leukocyte count, and PaO2/ FiO2. A total score of more than 6 was considered positive.

Statistical Analysis

The minimum required sample size to detect a statistically significant difference of 1.0 ± 1.4 units in the mCPIS score between groups was calculated as 32 patients per group, with a significance level (α) of 0.05 and power (1 - β) of 0.80. This analysis was conducted using G*Power version 3.1.

The normal distribution of numerical variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables between the two groups, while the Mann-Whitney U test was employed for the comparison of non-normally distributed variables. Relationships between categorical variables were tested using the chi-square test. SPSS 22.0 for Windows was used for the statistical analysis, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gaziantep University (Date: 2022-03-09, No: 2022/32).

Results

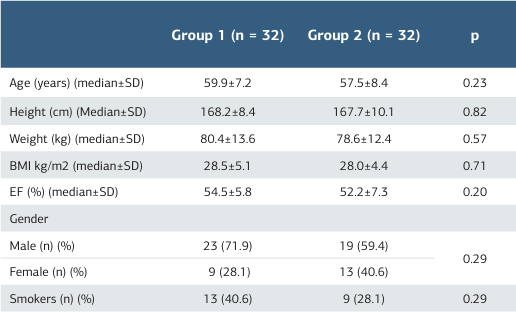

A total of 64 patients, 32 in each group, were included in the study. The demographic characteristics of the patients were compared and presented in Table 1. The mean age of the study patients was 58.7 years, with the youngest being 33 and the oldest 70 years old. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of the distribution of age (p = 0.23) of the patients between Groups 1 and 2. The average BMI of the patients was 28.2 kg m2-1. BMI values were comparable between both groups (p = 0.71). No statistically significant intergroup difference was observed regarding ejection fraction (EF) rates (p = 0.20), gender distribution (p = 0.29), and smoking status (p = 0.29).

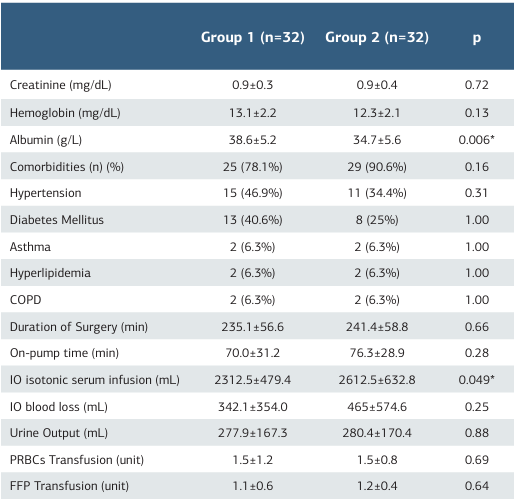

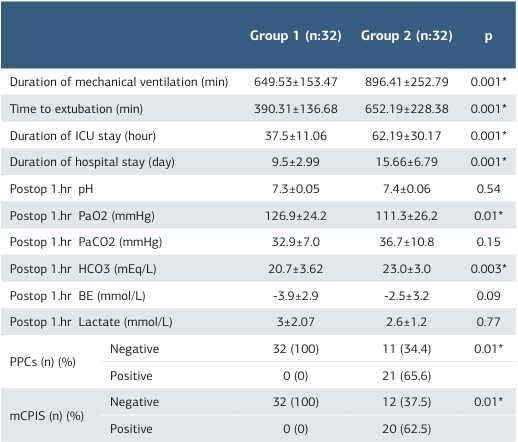

Both groups were compared in terms of creatinine, hemoglobin, and albumin values. No statistically significant intergroup difference was found in terms of creatinine (p = 0.72) and hemoglobin (p = 0.13) values. However, albumin values were statistically significantly higher in Group 1 (p = 0.006). There was no statistically significant intergroup difference regarding the prevalence of comorbidities (78.1%vs 90.6%), duration of surgery (235.1 ± 56.6 vs 241.4 ± 58.8 min), or CPB pump time (70.0 ± 31.2 vs 76.3 ± 28.9 min). The amount of intraoperative bleeding (p = 0.25) and urine output (p = 0.88) were comparable between groups. The amount of intraoperative isotonic serum infusion was statistically significantly higher in Group 1 than in Group 2 (2312.5 ± 479.4 vs 2612.5 ± 632.8 mL). Twelve patients in Group 1 and 16 patients in Group 2 received blood product transfusions. There was no significant intergroup difference concerning amounts of erythrocyte suspension (ES) (p = 0.69) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfused (p = 0.64) (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in terms of pH (p = 0.54), PaCO2 (p = 0.15), base excess (BE) (p = 0.09), and lactate (p = 0.77) values between Groups 1 and 2 based on the results of postoperative 6th-hour blood gas analysis. PaO2 values were significantly higher, while HCO3 values were significantly lower in Group 1 compared to Group 2 (p = 0.01) and (p = 0.03, respectively). Postoperative Pulmonary Complication and Modified Pulmonary Infection Scores in Group 1 were significantly lower than in Group 2 (for both: p = 0.001). Duration of mechanical ventilation (p = 0.001), time to extubation (p = 0.001), ICU (p = 0.001), and hospital stays (p = 0.001) were significantly shorter in Group 1 (Table 3).

Discussion

In our clinical study involving 64 patients undergoing on- pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery, we found that low tidal volume ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) significantly reduced Postoperative Pulmonary Complication Scores (PPCs) and the modified Clinical Pulmonary Infection Scores (mCPIS). Moreover, low tidal volume ventilation during CPB decreased the duration of mechanical ventilation, time to extubation, ICU, and hospital stays.

Previous studies have demonstrated that postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are a significant concern following cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), with an incidence rate as high as 6.2% 5. In their study examining postoperative complications in 103 patients undergoing cardiac surgeries, Bolukcu et al. reported that atelectasis was the most common cause of dyspnea. Furthermore, they mentioned that the patients who experienced dyspnea due to pneumonia had a longer ICU stay 6. In our study, the patients who had ventilated with low tidal volume during CPB had lower hospital and ICU stays.

Several studies have investigated predictors of PPCs, including hypoalbuminemia, advanced age, and CPB duration 7,8,9,10. On- pump cardiac surgery subjects patients to multiple pulmonary challenges. The combination of general anesthesia and invasive mechanical ventilation can lead to ventilator-induced lung injury 11. The application of LFV during CPB in valvular heart surgery demonstrated both feasibility and safety 12. Wang et al. 13 identified advanced age, female sex, and high BMI as significant demographic risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation. In patients undergoing elective CABG, lung biopsies and blood samples indicate that utilizing LFV during CPB, as opposed to leaving both lungs collapsed, does not appear to significantly decrease inflammation 14. An open-lung ventilation strategy, including moderate PEEP, recruitment maneuvers, and continued ventilation during CPB, enhanced dorsal lung ventilation during cardiac surgery 15.

The impact of CPB on lung injury is not fully understood, as many factors contribute to its development. Various interventions have been introduced to reduce the risk of lung damage, and many have shown positive results by lowering inflammation and improving recovery. However, because lung injury has multiple causes that are closely connected, a combination of different strategies is needed for effective prevention 16.

Maffezzoni et al. highlighted the ongoing debate about mechanical ventilation during CPB, noting that while some studies suggest benefits for oxygenation and inflammatory response, its overall clinical impact remains controversial 17. As for Boussion et al., low-tidal volume ventilation during CPB improves oxygenation and reduces lung injury 18. Our findings align with that study, supporting its role in reducing postoperative pulmonary complications.

Wang et al. 19 found that while positive airway pressure and ventilation during CPB improved immediate oxygenation, these benefits were transient and did not reduce long-term pulmonary complications. In contrast, our study demonstrates that low-tidal volume ventilation during CPB significantly reduces postoperative pulmonary complications.

Nguyen et al. conducted a large randomized study focusing on outcomes such as mortality and prolonged ventilation 20. While their study provides valuable insights into broader clinical outcomes, our study focuses on pulmonary-specific measures like PPCs and mCPIS.

The guidelines for CPB implementation, specifically in the lung protection section, suggest maintaining ventilation during the procedure (IIb/B recommendation) 21. In a randomized, double-blind clinical study by Zamani et al. 22, lung-protective strategy during and after CABG surgery significantly reduced postoperative mCPIS. These findings support our belief that low tidal volume, PEEP, and recruitment maneuvers can reduce postoperative pulmonary complications.

Costa Leme et al. conducted a study to determine whether an intensive alveolar recruitment strategy could reduce postoperative pulmonary complications when combined with protective low tidal volume ventilation. Although the results were not statistically significant, Group 1 had trends toward reduced oxygen requirements, fewer pulmonary complications, shorter ICU and hospital stays, and lower mortality 23. These outcomes are consistent with our findings, suggesting that protective ventilation strategies with alveolar recruitment during CPB may benefit pulmonary recovery.

Pulmonary artery perfusion during CPB may reduce hypoxemia by supporting lung metabolism 24. In our study, while low tidal volume ventilation likely contributed to better outcomes in Group 1, many factors may have also contributed.

Limitations

The limitations of our study include its retrospective design, the fact that it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the inability to assess pulmonary function before and after surgery. Additionally, the single-center nature of the study and the limited sample size may impact the generalizability of our findings. While our results suggest an association between lung ventilation during CPB and improved pulmonary outcomes, potential confounding factors must be considered.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that low tidal volume ventilation during CPB reduces the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications in coronary artery bypass grafting. Patients in the non-ventilated group experienced prolonged mechanical ventilation and longer ICU and hospital stays compared to the ventilated group, underscoring the potential benefits of this approach for improving postoperative outcomes.

Tables

Table 1. Demographic data of both groups

*Significant at p < 0.05, BMI: Body Mass Index, EF: Ejection Fraction

Table 2. Laboratory and clinical data of both groups

Significant at p < 0.05, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IO: Intraoperative, PRBCs: Packed Red Blood Cells, FFP: Fresh frozen plasma

Table 3. Outcome values of both groups

*Significant at p < 0.05, ICU: Intensive Care Unit PPCs: Postoperative Pulmonary Complica- tions Score, mCPIS: Modified Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score, BE: base excess: PaO2: Partial pressure of arterial oxygen, PaCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

References

-

Davies OJ, Husain T, Stephens RC. Postoperative pulmonary complications following non-cardiothoracic surgery. BJA Educ. 2017;17(9):295-300.

-

Zhang MQ, Liao YQ, Yu H, et al. Ventilation strategies with different inhaled oxygen concentrations during cardiopulmonary bypass in cardiac surgery (VONTCPB): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):254.

-

Huffmyer JL, Groves DS. Pulmonary complications of cardiopulmonary bypass. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2015;29(2):163-75.

-

Lagier D, Fischer F, Fornier W, et al. A perioperative surgeon-controlled open- lung approach versus conventional protective ventilation with low positive end- expiratory pressure in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (PROVECS): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):624.

-

Naveed A, Azam H, Murtaza HG, Ahmad RA, Baig MAR. Incidence and risk factors of pulmonary complications after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33(4):993–6.

-

Bolukcu A, Ilhan S, Topcu AC, Gunay R, Kayacioglu I. Causes of dyspnea after cardiac surgery. Turk Thorac J. 2018;19(4):165-9.

-

Setlers K, Jurcenko A, Arklina B, et al. Identifying early risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications in cardiac surgery patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(9):1398.

-

Manwani R, Gupta N, Kanakam S, Vora M, Bhaskaran K. Comparison of the effects of Ringer’s lactate and 6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 on blood loss and need for blood transfusion after off-pump coronary artery bypass graft cardiac surgery. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e16049.

-

Almeida CL, Oliveira JSB, Pires CGDS, Marinho CS. Risk assessment for postoperative complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgical procedures. Rev Bras Enferm. 2024;77(4):e20230127.

-

Hui V, Ho KM, Hahn R, Wright B, Larbalestier R, Pavey W. The association between intraoperative cardiopulmonary bypass power and complications after cardiac surgery. Perfusion. 2024;39(7):1304-13.

-

Wang Z, Cheng Q, Huang S, et al. Effect of perioperative sigh ventilation on postoperative hypoxemia and pulmonary complications after on-pump cardiac surgery (E-SIGHT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2024;25(1):585.

-

Rogers CA, Mazza G, Maishman R, et al. Low-frequency ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass to protect postoperative lung function in cardiac valvular surgery: the PROTECTION phase II randomized trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(19):e035011.

-

Wang Q, Tao Y, Zhang X, et al. The incidence, risk factors, and hospital mortality of prolonged mechanical ventilation among cardiac surgery patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2024;25(11):409.

-

Fiorentino F, Jaaly EA, Durham AL, et al. Low-frequency ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass for lung protection: A randomized controlled trial. J Card Surg. 2019;34(6):385-99.

-

Lagier D, Velly LJ, Guinard B, et al. Perioperative open-lung approach, regional ventilation, and lung injury in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2020;133(5):1029- 45.

-

Nteliopoulos G, Nikolakopoulou Z, Chow BHN, Corless R, Nguyen B, Dimarakis I. Lung injury following cardiopulmonary bypass: A clinical update. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2022;20(11):871-80.

-

Maffezzoni M, Bellini V. Con: Mechanical ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2024;38(4):1045-8.

-

Boussion K, Tremey B, Gibert H, et al. Efficacy of maintaining low-tidal volume mechanical ventilation as compared to resting lung strategy during coronary artery bypass graft cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: A posthoc analysis of the MECANO trial. J Clin Anesth. 2023;84(1):110991.

-

Wang YC, Huang CH, Tu YK. Effects of positive airway pressure and mechanical ventilation of the lungs during cardiopulmonary bypass on pulmonary adverse events after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(2):748-59.

-

Nguyen LS, Estagnasie P, Merzoug M, et al. Low-tidal volume mechanical ventilation against no ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass in heart surgery (MECANO): A randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2021;159(5):1843-53.

-

Hessel EA, Groom RC. Guidelines for conduct of cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35(1):1-17.

-

Zamani MM, Najafi A, Sehat S, et al. The effect of intraoperative lung protective ventilation vs conventional ventilation on postoperative pulmonary complications after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2017;9(4):221-8.

-

Costa Leme A, Hajjar LA, Volpe MS, et al. Effect of intensive vs moderate alveolar recruitment strategies added to lung-protective ventilation on postoperative pulmonary complications: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1422-32.

-

Buggeskov KB. Pulmonary artery perfusion versus no pulmonary perfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass. Dan Med J. 2018;65(3):B5473.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gaziantep University (Date: 2022-03-09, No: 2022/32)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Gökhan Güllü, Elzem Sen. The effects of low tidal volume ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass on postoperative pulmonary complications. Ann Clin Anal Med 2025;16(12):878-882

Publication History

- Received:

- March 9, 2025

- Accepted:

- April 15, 2025

- Published Online:

- April 28, 2025

- Printed:

- December 1, 2025