Mandibular trabecular structures of different sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns with dentoalveolar compensation

Mandibular trabecular structures with dentoalveolar compensation

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study was undertaken to examine the fractal dimension (FD) results of mandibular structures with different sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns in the presence of dentoalveolar compensation.

Methods The panoramic films of 135 patients (93 female and 42 male; mean age: 14.90±1.54 years) with a normal incisor relationship were involved in this study. The study groups were performed based on the anteroposterior and vertical skeletal patterns as Class I hypo-, normo-, and hyperdivergent groups, and in the same manner for Class II and III compensated subjects. The mandibular structures were bilaterally selected as regions of interest (ROI), including the condyle, angulus, and corpus. The fractal analysis was used to calculate the mean or median FD values for each ROI. Data were analyzed statistically.

Results Only significance was found with the right angulus of Class II compensated subjects. The right angulus mean FD value was significantly lower in the normodivergent group than in the hypo- and hyperdivergent groups (p<0.05). No significant differences were found between the FD values of right and left mandibular structures.

Conclusion The fractal results, with one exception, demonstrated that mandibular trabecular structures of various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns were unaffected by compensation. In comparison to the other groups, the Class II normodivergent group had a much lower FD value in terms of right angulus.

Keywords

Introduction

Depending on various growth patterns of the skull base, different vertical dimensions can be encountered in all types of sagittal malocclusions 1. Differences in skeletal vertical dimension are mainly associated with the type of mandibular rotation 2. Excessive mandibular backward rotation causes increased vertical dimension, and vice versa 3.

Dentoalveolar compensation is a system that can establish a normal relationship with the changes of skeletal structures. The compensatory mechanism includes the alterations of dentoalveolar height and incisor inclinations 4. All compensations aim to camouflage the malocclusion to preserve the overall balance and ratios of the dentofacial components 5. Despite this, aesthetic concerns are an important key to treatment planning in terms of achieving successful results in adults. At this point, the decompensation is inevitable for the surgical treatment planning 6. Therefore, it would be helpful to understand the trabecular structure of the mandible.

Fractal analysis is a non-invasive and quantitative technique employed to examine the complex structure of trabecular bone and its pattern. The obtained numerical value is defined as the fractal dimension (FD), which is a calculation of structural complexity. That is, an increase of FD value corresponds to a rise in the complexity of the structure. In this context, the panoramic radiographs are suggested as a reliable method, especially to evaluate the mandibular bone structure 7.

The fractal analysis of mandibular trabecular bone has received much attention for the past five years in orthodontic literature 8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Previous studies have only focused on the mandibular structures in different sagittal malocclusions with normal growth patterns 9,14. Despite this interest, no evaluation has been made on various sagittal malocclusions and vertical growth patterns in the presence of dentoalveolar compensation. This study aimed to assess the mandibular structures using fractal analysis in different sagittal skeletal and vertical growth patterns accompanied by dentoalveolar compensation. We hypothesized that there would be no differences between different vertical growth patterns of sagittal malocclusions in the presence of dentoalveolar compensation.

Materials and Methods

The archive records of the orthodontic department, between 2020 and 2023, were used to investigate the mandibular structures of dentally compensated subjects with various anteroposterior and vertical skeletal patterns via fractal dimension analysis.

Sample Size

The power analysis (G*Power vers. 3.1.9.7; Franz Faul, Kiel University) showed that at least 15 subjects would be necessary to achieve 80% power at a 95% confidence level, assuming that the effect size of the change to be examined would be at a large level (f = 0.40) for each group.

Study Sample

The pre-treatment archive records of 135 orthodontic patients (93 female and 42 male) with a mean age of 14.90±1.54 years) with a normal incisor relationship (1-3 mm) were involved in this study. Exclusion criteria were defined as systemic disease or drug use that may affect bone metabolism, symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorder, history of trauma and previous orthodontic treatment, missing teeth except the third molar tooth, and the cervical vertebra maturation stage under 4 15.

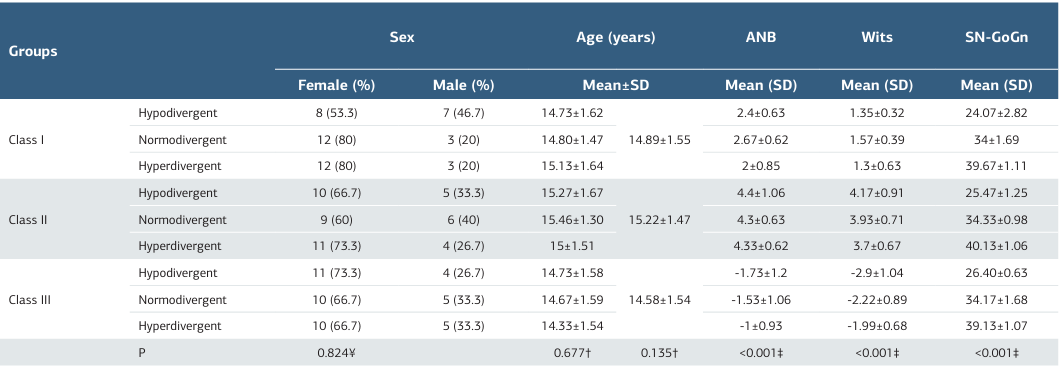

Based on the cephalometric analysis, subjects were first divided into three main groups by their sagittal skeletal patterns. The anteroposterior apical base discrepancy was determined with the ANB angle described by Steiner as Class I (0°<ANB<4°), Class II (ANB>4°), and Class III (ANB<0°) 16. Due to the limitations of the ANB angle, the Wits measurement is also used to categorize the sagittal skeletal pattern 17. Subsequently, the SN-GoGn angle was used to determine the vertical growth pattern and classified as hypo-, normo-, and hyperdivergent based on the adjusted Turkish norm (SN-GoGn=30.5±4.5°) of Steiner analysis 18.

The three main study groups and their subgroups were as follows: Class I hypo- (8 female and 7 male, mean:14.73±1.62 years), normo- (12 female and 3 male, mean:14.80±1.47 years), and hyperdivergent (12 female and 3 male, mean:15.13±1.64 years); Class II hypo- (10 female and 5 male, mean: 15.27±1.67 years), normo- (9 female and 6 male, mean: 15.46±1.30 years), and hyperdivergent (15±1.51 years; Class III hypo- (11 female and 4 male, mean:14.73±1.58), normo- (10 female and 5 male, mean: 14.67±1.59 years), and hyperdivergent (10 female and 5 male, mean: 14.33±1.54 years).

Fractal Dimension Analysis

The panoramic radiographs with sufficient image quality, with no artifacts, absence of any pathology involving the mandibular corpus, angulus, and condylar region were used in this study. The standardized panoramic radiographs were obtained with the same dental imaging device (OP200D; Instrumentarium Corp., Imaging Division, Tuusula, Finland) following the same scanning parameters (60 kV, 6.3 mA, 14.1 s exposure time). All radiographs were evaluated by a blinded dentomaxillofacial radiologist (G.A) with 8 years of clinical experience on the same computer. The image analysis was carried out on TIFF format using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and the box counting fractal analysis method was employed for this assessment 19.

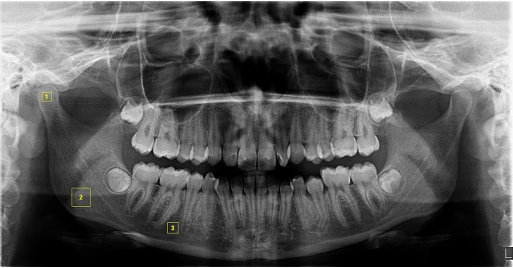

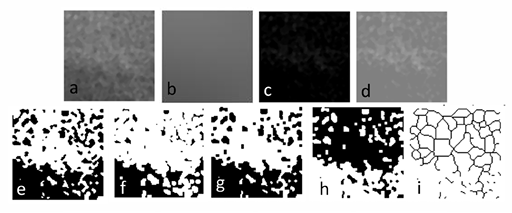

Region of interest (ROI) was selected bilaterally with dimensions of 50x50 pixels in the mandibular condyle, 100x100 pixels in the angulus, and 60x60 pixels in the corpus (between the second premolar and first molar) as shown in Figure 1. After the duplication of each ROI (Figure 2a), one copy was blurred using the Gaussian filter (sigma=35 pixels) (Figure 2b). The resulting image was removed from the original (Figure 2c), and 128 shades of gray were added for each pixel location (Figure 2d). Every image was changed to an 8-bit format. Then, the trabecular and bone marrow outlines were identified with the “Threshold” tab (Figure 2e). The noise was reduced using the “Erode” tab (Figure 2f), and then structures were made visible using the “Dilate” tab (Figure 2g). The “Invert” tab was used to turn the black areas white and vice versa (Figure 2h). As necessary lines for fractal analysis, the trabecular skeleton outlines were displayed using the “Skeletonize” tab (Figure 2i). Finally, the image was divided into squares of 2,3,4,6,8,12,16,32,64 pixels with the “Fractal box counting” under the “Analyze” tab, and the fractal dimension (FD) value was calculated. The same steps were applied for each panoramic radiograph. After one month, half of the randomly selected radiographs were secondly examined by the same researcher to assess the measurement reliability.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted on SPSS software (vers 22; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze data distribution. The results were demonstrated as mean (±) standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed corpus FD values of the Class II group and median (interquartile range [IQR]) for the other non-normal parameters.

The one-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the FD values of left or right mandibular structures in terms of different vertical growth patterns. The Student’s t and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to evaluate the differences between the right and left sides. An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate the intraexaminer reliability. The significance was accepted as p<0.05.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pamukkale University (Date: 2024-01-09, No: E-60116787-020-483660).

Results

There were no gender or age differences between the groups. The ANB, Wits, and SN-GoGn measurements defined the characteristics of compensation groups to be examined in this study, as shown in Table 1.

The measurement repeatability showed good to excellent agreement. All ICC values ranged from 0.75 to 0.91 and separately for the right condyle (ICC=0.881, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.783-0.934), angulus (ICC=0.915, 95% [CI]=0.845- 0.953) and corpus (ICC=0.877, 95% [CI]=0.777-0.933) and left condyle (ICC=0.746, 95% [CI]=0.538-0.861), left angulus (ICC=0.899, 95% [CI]=0.817-0.945) and left corpus (ICC=0.828, 95% [CI]=0.688-0.906).

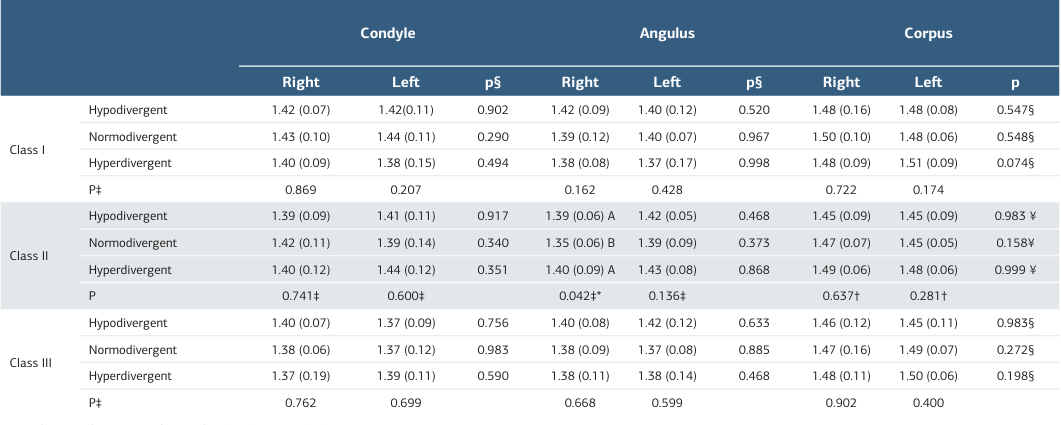

The fractal analysis results of mandibular structures are demonstrated in Table 2. The FD values were the highest in the corpus region regardless of various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns. With one exception, there were no significant differences in the FD values of right and left mandibular structures of different sagittal and vertical growth patterns. Only significance was determined in the right angulus of Class II group. (p=0.042, p˂0.05). The FD values were significantly higher in hypo- and hyperdivergent growth patterns than in normal.

Discussion

Dentoalveolar compensation camouflages the skeletal discrepancies that cause anomalies in the sagittal and vertical dimensions. The deviations from ideal jaw relationships can be accomplished with compensatory changes, which may subsequently result in structural changes within the jaws. A normal incisor relationship can be obtained with a dentoalveolar compensation related to changes in skeletal patterns 5. In this study, the FD values of mandibular structures were examined in terms of dentoalveolar compensation with varying skeletal patterns. According to the complexity of the mandibular trabecular bone, increased or decreased FD values were recorded in the selected ROIs.

The fractal analysis was used to assess the trabecular structure, considering its advantages, such as numerical data by calculating FD, a non-invasive technique, and reliable usability with panoramic radiographs during this study 7. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first time that fractal analysis was used for evaluating the mandibular trabecular structures of compensated subjects with various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns. There were no significant differences between the right and left sides in terms of FD findings. For each side, the FD values of mandibular structures were not significantly different in Class I and III compensated groups among different vertical growth patterns. However, the angulus FD values of Class II subjects with hypo- and hyperdivergent growth patterns differed from the normal in the presence of dentoalveolar compensation. The results for the right angulus were significantly higher for the aforementioned two compared to the normodivergent subgroup. This finding might be caused by the compensatory changes of morphological structures observed in Class subjects.

It is a well-known fact that the activity of the masticatory muscles affects the angulus region, which could be the cause of bony changes 20. To the degree that all variables are balanced, compensatory muscle activity increases the structural abnormality 21. Accordingly, the hypo- and hyperdivergent Class II groups have noticeably higher FD values associated with the complexity of the angulus. The skeletal structural changes may be the result of the variations regarding muscular characteristics 22. In this study, Class II normodivergent subjects had more porous angular structures than other subjects. In a recent study that assessed the trabecular structure of normodivergent subjects with various sagittal skeletal patterns, angulus was identified as one of the ROIs in which significant differences were found, irrespective of compensation 14. Supporting our findings, the FD values of the angulus region were higher in the Class I and III groups than in the Class II group with a normodivergent growth pattern.

According to our findings, the observed variations in trabecular structure between various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns could play a critical role in treatment planning, either compensation with tooth movement or decompensation with a surgical approach. Recent studies have highlighted the clinical significance of FD differences and concluded that they may have an impact on bone healing from a surgical perspective 23,24. The evidence from this study points out that angulus FD would be a valuable parameter for a compensated Class II malocclusion when decompensation is inevitable for surgery treatment planning. For instance, a more complex angular structure may alter the surgical procedure.

Limitations

The significance of fractal analysis of mandibular structures when dentoalveolar compensation takes place in various sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns has been highlighted by this orthodontic research. However, it is essential to point out the consequences of the findings in light of limitations. The gender heterogeneity of the sample size is one drawback. Another is a dearth of knowledge about possible differences caused by characteristics of the masticatory muscles. It should be kept in mind that future studies on dentoalveolar compensation should be conducted with additional evaluation of masticatory muscular activity to provide comprehensive data on this topic.

Conclusion

As a result, the null hypothesis was rejected. The FD value of the right angulus was significantly lower in the normodivergent compared with hypo- and hyperdivergent Class II compensations. Apart from this finding, no significant FD differences were found in the Class I and III compensated subjects with various vertical skeletal patterns. Besides, the mandibular structures revealed similar FD results on dentoalveolar compensated subjects with varying skeletal patterns between left and right sides. In summary, our findings support the idea that the FD analysis presents a new opinion to determine the bone structure of Class II compensated cases.

Figures

Figure 1. Determination of the regions of interest (ROIs) on the panoramic radiography. The yellow squares indicate the ROIs; 1, mandibular condyle region (50 x 50); 2, mandibular angulus region (100 x 100); 3, mandibular corpus region (60 x 60)

Figure 2. Fractal dimension analysis processes. (a) the cropped and duplicated ROI, (b) blurring of the duplicated image by applying the Gaussian blur filter, (c) subtraction of the blurred image from the original image, (d) addition of 128 shades of gray, (e) threshold process, (f) erode process, (g) dilate process, (h) invert process, (i) skeletonization

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of demographic and cephalometric characteristics of study groups

¥ Chi-square test; † One-way ANOVA test; ‡ Kruskal-Wallis test

Table 2. Comparison of fractal dimension (FD) of mandibular structures in Class I, II and III compensations with different vertical dimensions

FD values are demonstrated as median (IQR) or mean (SD) † One-Way ANOVA; ‡ Kruskal Wallis test; § Mann Whitney U test; ¥ Student t-test Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different vertical skeletal patterns * indicates p˂0.05

References

-

Sassouni V. A classification of skeletal facial types. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(2):109-23.

-

Björk A. Prediction of mandibular growth rotation. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(6):585- 99.

-

Nanda SK. Patterns of vertical growth in the face. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93(2):103-16.

-

Worms FW, Isaacson RJ, Speidel TM. Surgical orthodontic treatment planning: profile analysis and mandibular surgery. Angle Orthod. 1976;46(1):1-25.

-

Solow B. The dentoalveolar compensatory mechanism: background and clinical implications. Br J Orthod. 1980;7(3):145-61.

-

Larson BE. Orthodontic preparation for orthognathic surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2014;26(4):441-58.

-

Kato CN, Barra SG, Tavares NP, et al. Use of fractal analysis in dental images: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2020;49(2):20180457.

-

Cesur E, Bayrak S, Kursun-Çakmak EŞ, Arslan C, Köklü A, Orhan K. Evaluating the effects of functional orthodontic treatment on mandibular osseous structure using fractal dimension analysis of dental panoramic radiographs. Angle Orthod. 2020;90(6):783-93.

-

Korkmaz YN, Arslan S. Evaluation of the trabecular structure of the mandibular condyles by fractal analysis in patients with different dentofacial skeletal patterns. Austral Orthod J. 2021;137(1):93-9.

-

Amuk M, Gul Amuk N, Yılmaz S. Treatment and posttreatment effects of Herbst appliance therapy on trabecular structure of the mandible using fractal dimension analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2022;44(2):125-33.

-

Köse E, Ay Ünüvar Y, Uzun M. Assessment of the relationship between fractal analysis of mandibular bone and orthodontic treatment duration: A retrospective study. J Orofac Orthop. 2022;83(Suppl 1):102-10.

-

Arslan S, Korkmaz YN, Buyuk SK, Tekin B. Effects of reverse headgear therapy on mandibular trabecular structure: a fractal analysis study. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2022; 25(4):562-8.

-

Bolat Gümüş E, Yavuz E, Tufekci C. Effects of functional orthopedic treatment on mandibular trabecular bone in class II patients using fractal analysis. J Orofac Orthop. 2023;84(Suppl 3):155-64.

-

Tercanlı H, Bolat Gümüş E. Evaluation of mandibular trabecular bone structure in growing children with Class I, II, and III malocclusions using fractal analysis: A retrospective study. Int Orthod. 2024;22(3):100875

-

Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr. The cervical vertebral maturation method for the assessment of optimal treatment timing in dentofacial orthopedics. Semin Orthod. 2005;11(3):119-29.

-

Steiner CC. Cephalometrics for you and me. Am J Orthod. 1953;39(10):729-55.

-

Jacobson A. Update on the Wits appraisal. Angle Orthod. 1988;58(3):205-19.

-

Steiner CC. The use of cephalometrics as an aid to planning and assessing orthodontic treatment: report of a case. Am J Orthod. 1960;46(10):721–35.

-

White SC, Rudolph DJ. Alterations of the trabecular pattern of the jaws in patients with osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88(5):628-35.

-

Sella-Tunis T, Pokhojaev A, Sarig R, O’Higgins P, May H. Human mandibular shape is associated with masticatory muscle force. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6042.

-

Grabber TM. The “three M’s”: muscles, malformation, and malocclusion. Am J Orthod. 1963;49(6):418-50.

-

Togninalli D, Antonarakis GS, Papadopoulou AK. Relationship between craniofacial skeletal patterns and anatomic characteristics of masticatory muscles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Orthod. 2024;25(1):36.

-

Muftuoglu O, Karasu HA. Assessment of mandibular bony healing, mandibular condyle, and angulus after orthognathic surgery using fractal dimension method. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2024;29(5):e620-5.

-

Rahajoe PS, Sukawijaksa H, Arindra PK, Diba SF. Evaluation of bone healing in the trabeculae structure of mandibular corpus and angulus fracture patients with fractal dimension analysis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2025;15(1):205-11.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pamukkale University (Date: 2024-01-09, No: E-60116787-020-483660)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Serpil Çokakoğlu, Gözde Açıkgöz, Güneş Dönem Kıraslan. Mandibular trabecular structures of different sagittal and vertical skeletal patterns with dentoalveolar compensation. Ann Clin Anal Med 2025;16(12):883-887

Publication History

- Received:

- March 10, 2025

- Accepted:

- April 15, 2025

- Published Online:

- May 9, 2025

- Printed:

- December 1, 2025