Chestnut-burr spine-related corneal injury: a case report

Chestnut-burr spine-related corneal injury

Authors

Abstract

Introduction Chestnuts represent a type of fruit characterized by multiple nuts that are surrounded by a spiny burr. These stiff and sharp spines can cause severe ocular injuries, including corneal, scleral, and conjunctival foreign body-related damage with or without laceration, penetrating trauma, keratitis, traumatic cataract, and endophthalmitis.

Case Presentation We report two patients who were admitted to our clinic following trauma caused by chestnut burrs during the harvesting season. Slit-lamp examination revealed intrastromally embedded chestnut burrs in the mid-peripheral cornea, without penetration into the anterior chamber, in both patients. Corneal spines were removed on the same day, using a 26-gauge needle to reach deep below the spine and extract it. At the first postoperative visit, both patients demonstrated a visual acuity of 1.0. No complications developed during the patient’s follow-up, and wound healing was completed without any problems.

Conclusion This case highlights the potential risks of ingested foreign bodies and underscores the importance of early surgical intervention and appropriate medical treatment.

Keywords

Introduction

Chestnuts represent a type of fruit characterized by multiple nuts that are surrounded by a spiny burr. These burrs can grow to be substantial spines, reaching diameters of as much as 10 centimeters (Figure 1). Proper gloves are essential when dealing with burrs, as the sharp spines can penetrate the protective fabric and cause skin irritation, even when gloves are worn. The collection of the fruit is performed using conventional techniques, where individuals manually strike the chestnut tree with an extended stick, and then they collect the burrs from the ground with a unique type of rake. Individuals who do not wear suitable eye protection while managing chestnuts risk having the spines of the chestnut burr penetrate unprotected areas of their eyes, including the eyelid, cornea, anterior sclera, or even intraocular tissues. These stiff and sharp spines can cause severe ocular injuries including corneal, scleral, and conjunctival foreign body-related damage with or without laceration, penetrating trauma, keratitis, traumatic cataracts, and endophthalmitis 1,2,3.

We present two patients who were admitted to our clinic following trauma caused by chestnut burrs during the harvesting season.

Case Presentation

Case 1

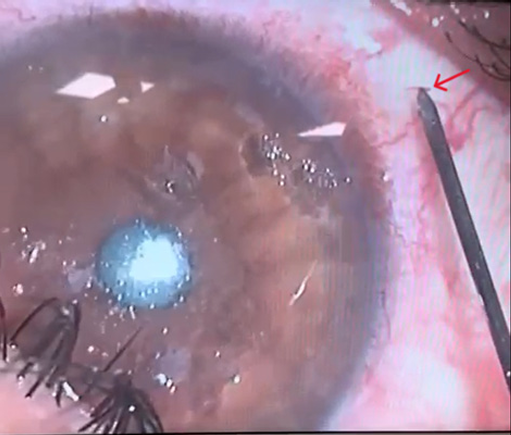

A 36-year-old man presented with a foreign body sensation and blurred vision in his left eye following an eye injury caused by a chestnut. Best-corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 0.7 (decimal), with an intraocular pressure of 16 mmHg. The upper eyelid showed significant swelling and ciliary injection was noted. Slit-lamp examination revealed nine intrastromally embedded chestnut burrs in the mid-peripheral cornea, without penetration into the anterior chamber (Figure 2). No signs of anterior chamber inflammation were observed, and Seidel’s test was negative. A dilated fundus examination showed no vitreous reaction, with a normal optic disc and macula.

Case 2

A 53-year-old man was admitted to the ophthalmology department with blurred vision, tearing, and a foreign body sensation in his left eye after being struck by a chestnut one day earlier. Edema was observed in the upper left eyelid. Best- corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 1.0 (decimal), and the intraocular pressure was 13 mmHg. The slit-lamp assessment identified seven chestnut burrs embedded in the mid-peripheral corneal stroma, with no involvement of the anterior chamber. Ciliary injection was noted. The anterior chamber showed no signs of active inflammation, and Seidel’s test was negative. In the dilated eye examination, no vitreous reaction was observed, and the optic disc and macula were evaluated to be normal.

Corneal spines were removed on the same day, using a 26 gauge needle to reach deep below the spine and extract it (Figure 3). Both patients were put on topical antibiotics (0.5% moxifloxacin hydrochloride, 5 times a day), antifungals (0.3% fluconazole, 5 times a day). Patients also underwent topical 1% fusidic acid and 0.5% tropicamide two times daily, along with preservative-free artificial tears.

At the first postoperative visit, both patients demonstrated a visual acuity 1.0 (decimal), and their intraocular pressure was within normal limits. Needle entry sites showed mild edema. Seidel’s test was evaluated as negative and no reaction was observed in the anterior chamber. However, it was noted that the ciliary injection persisted. The vitreous was clear and no pathology was found in the retinal examination. No complications developed during the patient’s follow-up and wound healing was completed without any problems.

Ethical Approval

This study did not require ethical approval according to the relevant guidelines.

Informed Consent

Obtained.

Discussion

In the present cases, the burrs were embedded within the stroma of the cornea, specifically in the mid-peripheral area, without penetrating the anterior chamber. Due to their delicate and fibrous nature, the spines of chestnut burrs frequently fracture and become embedded in the stroma of the cornea and sclera or within the eyelid. They are sharp enough to penetrate the eye globe and reach into the anterior chamber, so they are likely to cause a wide spectrum of eye traumas, including corneal and scleral foreign bodies, keratitis, hyphema, traumatic cataracts, abscesses of the sclera, and endophthalmitis 1,2,3. These spines, because of their properties, might go unnoticed during a slit lamp examination, especially if they are positioned beneath the episcleral tissue. Wang et al. indicated that in patients with suspected or definitive intrascleral spine diagnoses, UBM examination is appropriate to exclude the presence of retained spines 4.

Delaying the removal of chestnut burr spines can trigger inflammation, infections, toxic effects, and granulomatous reactions. In certain cases, reports in the literature suggest that monitoring may be a viable strategy for spines located deep within the stroma due to the challenges associated with their extraction. Garcia-Garcia et al. reported an asymptomatic case with chronic retention of intrastromal chestnut-burr spines for 5 years 1. Similarly in their study Karaca et al. reported 19 patients with chronically retained intrastromal chestnut burr 2. It is shown that the spines of chestnuts contain a compound called escin, which is reported to demonstrate antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles in addition to its anti-edema, antitumoral, antiviral, and antifungal roles 5,6. Furthermore, it was highlighted that surgical procedures involving more extensive penetration into the stroma typically present a greater risk of corneal opacification when compared to observation alone.

The surgical approach is required and recommended for larger and symptomatic spines. In the cases presented, foreign bodies were suitable for needle removal because they were placed in the mid-peripheral cornea and were not deeply located. Tangential keratotomy with a 15-degree knife and femtosecond laser-assisted removal were other proposed methods in cases of deep corneal localization, for better clinical outcomes in terms of corneal clarity 1,7.

Prophylactic initiation of topical antifungals, 0.3% fluconazole is crucial for chestnut-burr spine-related corneal injuries. The association between injuries from chestnut burrs and the development of fungal infections has been well-documented. Investigations have revealed that the spines of chestnut burrs harbor certain fungal species, which are implicated in these infections 3. Since untreated fungal keratitis can result in serious complications, it is crucial to begin topical antifungal treatment immediately upon diagnosis.

In their research, Zhang et al retrospectively studied 502 eyes with chestnut burr-related ocular injuries and found that none of the patients had been wearing any kind of eye protection when the trauma occurred 3. By increasing the use of eye protection, many of these injuries could likely be avoided; therefore, public health education should be advised.

Limitations

The main limitation of our report was that there was a limited number of patients.

Conclusion

This case reveals the potential risks of organic foreign bodies and highlights the importance of early surgery and appropriate medical treatment.

Figures

Figure 1. Chestnut

Figure 2. Corneal chestnut burr

Figure 3. Removal of the foreign body

References

-

García-García GP, Esaa-Caride NC, Jurado-Guano ND, Muñoz-Bellido L. Ocular injury with chestnut burr: our experience. Cornea. 2016;35(10):1315-9. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000952.

-

Karaca I, Barut Selver O, Palamar M, Egrilmez S. Chronically retained feathery chestnut-burr spine-related corneal injury: clinical features and outcome. Int Ophthalmol. 2020;40(8):1993-7. doi:10.1007/s10792-020-01374-9.

-

Zhang ZD, Huang MK, Zhou R, Qu J. A 7-year retrospective study for clinical features and visual outcome of chestnut burr-related ocular injuries. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(6):1247-9. doi:10.1007/s00417-012-2104-7.

-

Wang M, Deng W, Li J, Cong R, Xiao T. Management of intrascleral chestnut burr spines under ultrasound biomicroscopy guidance. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(9):3311-5. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_356_22.

-

Gallelli L. Escin: a review of its anti-edematous, anti-inflammatory, and venotonic properties. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3425-37. doi:10.2147/DDDT. S207720.

-

Vašková J, Fejerčáková A, Mojžišová G, Vaško L, Patlevič P. Antioxidant potential of Aesculus hippocastanum extract and escin against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(5):879-86. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201503_5724.

-

Qin YJ, Zeng J, Lin HL, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted removal of an intracorneal chestnut, a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18(1):210. doi:10.1186/s12886-018-0875-2.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Emre Okur, Meltem Toklu, Burak Turgut. Chestnut-burr spine-related corneal injury: a case report. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(1):84-86

Publication History

- Received:

- March 17, 2025

- Accepted:

- April 24, 2025

- Published Online:

- May 1, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026