Using cadaveric sheep head models for transnasal transsphenoidal pituitary surgery training in neurosurgery

Pituitary surgery training with sheep head model

Authors

Abstract

Aim Skull base training in neurosurgery is challenging due to difficult anatomical variations in brain tissue, adjacent vascular structures, and cranial nerves. The aim of our study was to develop a cadaveric sheep head model simulating transnasal transsphenoidal pituitary surgery for neurosurgery residents to receive basic anatomical training and develop the necessary neurosurgical skills.

Methods The material consists of veterinary-controlled sheep heads with the scalp removed from a local butcher.

Results The skull was placed in a neutral position. The inferior turbinate was lateralized. The nasal septum was found, and preparation was made for the flap. The nasoseptal flap was overturned. The sphenoid sinus was drilled with a hand drill. After identifying the anatomical landmarks, the sella floor was opened, and the sella dura was reached. In the final stage, the surgical field was closed with a nasoseptal flap.

Conclusion The use of cadaveric sheep head models in the study, even though it is not a model with a blood supply, increases familiarity with the stages of surgery and mimics the endoscope maneuvers appropriate to the stages, suggesting that it will help to pass the learning steps in real surgery more quickly and safely.

Keywords

Introduction

There is a growing need for laboratory training models in neurosurgery to help residents develop surgical skills and reinforce their knowledge before transitioning to clinical practice 1. Several models have been developed to provide residents with experience in microsurgical and endoscopic procedures. Most of these models utilize cadaveric or animal- derived tissues, or synthetic materials 2. The sheep skull model serves as a viable alternative to human cadavers. Sheep models have been extensively employed across multiple surgical training applications, such as anterior clinoidectomy 3, endoscopic cordotomy 4, retrosigmoid approach extensions 5, and posterior fossa microneurosurgical approaches 6. This model offers several advantages: the internal nasal structure of sheep is similar to that of humans, allowing residents to handle fresh organic tissue, perform microsurgical and endoscopic interventions, and practice using microneurosurgical instruments and endoscopic tools in a three-dimensional surgical field that simulates real surgery 7. Additional benefits include its low cost, easy availability, and the absence of a need for specialized facilities or live animal anesthesia. Furthermore, this model does not require ethical approval. However, a significant limitation is the lack of a blood supply, which is present in living tissue. Additionally, there is a theoretical risk of exposure to slow viruses, such as those causing mad cow disease, when using sheep heads 8. To mitigate this risk, it is recommended that the heads be sourced from known, veterinary-controlled animals, and all sterilization protocols must be strictly followed. The cadaveric sheep model is specifically designed for laboratory training, enabling neurosurgery residents to familiarize themselves with endoscopic hypophysectomy procedures.

This study was conducted using a transnasal approach. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the cadaveric sheep head model in training for endoscopic hypophysectomy, a complex neurosurgical procedure that involves delicate manipulations during transsphenoidal pituitary surgery.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were conducted in the Experimental Animal Research Laboratory of Ankara Education and Research Hospital. The study material consisted of 5 scalped sheep heads obtained from a local butcher (US$ 4.00/each). After collection, the head was stored in a refrigerator at 4°C for six hours.

Surgical Steps

The sheep skulls were positioned anteriorly, and after nasal irrigation, endoscopic examination revealed the bipartite inferior turbinate. The nasoseptal flap was elevated to access the sphenoid sinus, where drilling exposed the anterior wall. The sella turcica floor was then opened, and the dura was visualized before final closure with the nasoseptal flap, mirroring human skull base techniques.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ankara Education and Research Hospital Animal Experiments (Date: 2024-11-01, No: 799).

Results

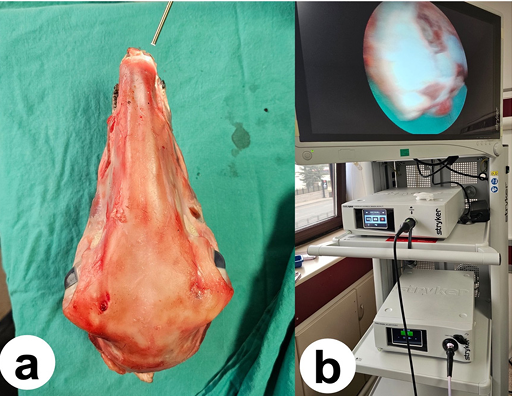

The sheep skulls were positioned in a neutral orientation facing the operator (Figure 1a), and the nasal cavities were irrigated with saline solution. A Stryker-brand endoscope was used for the procedure (Figure 1b). Unlike humans, the inferior turbinate in sheep is divided into two parts. The primary inferior turbinate and middle turbinate were visualized through lateralization (Figure 2a). Next, the nasoseptal flap was reflected (Figure 2b). A middle turbinate dissector was used to lateralize the turbinate, and the anterior surface of the sphenoid sinus was accessed. The anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus was then drilled using an extended hand drill (Figures 2c and 3a). After identifying the anatomical landmarks, the floor of the sella turcica was opened, and the sella dura was exposed using a Kerrison rongeur (Figure 3b). Finally, the surgical field was closed using the nasoseptal flap.

Discussion

Skull base training in neurosurgery is particularly challenging due to the intricate anatomical variations in brain tissue, adjacent vascular structures, and cranial nerves 9. The complexity of this region demands extensive knowledge and technical expertise. As one of the most technically demanding areas in neurosurgery, detailed and intensive training is essential to develop the skills required for safe and effective surgical approaches 10. Training neurosurgery residents in a controlled laboratory environment is crucial for maintaining the competence of experienced surgeons 11,12. Such training allows residents to practice critical techniques, including microsurgical manipulation, tissue dissection, and fine motor skills under microscope magnification, providing essential preparation for real-life surgical procedures in the operating room 13,14.

In neurosurgery, repetitive practice is vital for the development of surgical skills 15. Microsurgical proficiency is achieved by mastering the fine manual dexterity required for delicate procedures on small and complex structures 16,17. Tactile sensitivity, which involves distinguishing tissue types by touch during dissection, is essential for minimizing damage to surrounding structures 18,19. Familiarity with microscope magnification is also critical for enhancing surgical safety and precision. Residents must develop confidence in working with limited visibility through the microscope 20.

Human cadavers are typically used in laboratory training to closely simulate the surgical environment. Cadaveric models provide realistic tactile feedback and allow residents to work with critical anatomical structures using microsurgical instruments on real biological tissue 1,21. However, these models are expensive, making them inaccessible in many regions, and their use may be limited by cultural or ethical restrictions 22,23. While there are anatomical differences between humans and small animals, sheep cadaver models offer similar tactile feedback, particularly during bone drilling and dural dissection. Moreover, sheep cadavers are a practical and cost-effective option for training in developing countries, as they are affordable, ethically acceptable, and culturally permissible in settings where human cadavers are unavailable 4,7.

The use of animal models offers several advantages. First, they are significantly more economical than human cadavers. Although there are visual differences, the anatomical landmarks in sheep are comparable to human structures, enabling trainees to study anatomical relationships and adapt to variations encountered in human surgery 3.

This study presents the first documented use of a sheep head model for training in endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. While prior research has examined anterior fossa anatomy in sheep models, our described techniques represent a novel contribution to the literature. Our findings demonstrate close anatomical parallels between sheep and human nasal and sphenoid structures. Furthermore, sheep heads prove to be a more economical alternative to human cadavers for neurosurgical training purposes. The study also revealed that pituitary region anatomy in sheep shows no substantial differences from human anatomy.

Limitations

Since this is a cadaveric model, it does not simulate blood flow. The inability to preserve the cavernous sinus—a major limitation—increases the risk of carotid artery injury, representing a key area for improvement. Additionally, sheep cranial anatomy does not perfectly mirror human anatomy, further limiting the model’s applicability. Sourcing specimens from non-certified suppliers also raises concerns about potential slow virus transmission.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the fresh cadaveric sheep head model is a valuable tool for training neurosurgery residents in transnasal transsphenoidal hypophysectomy. It provides an effective method for familiarizing trainees with the basic steps of the procedure and simulates real-life surgical conditions. However, training on sheep cadavers should not replace other forms of anatomical training; rather, it should serve as a complementary model, particularly for beginners.

Figures

Figure 1. a) Skull positioned in a neutral orientation, b) Endoscopy device used during the procedure

Figure 2. a) Visualization of the inferior turbinate following endoscope lateralization, b) Preparation of the nasoseptal flap; the arrow indicates the nasoseptal flap, c) Drilling of the sphenoid sinus

Figure 3. a) Use of an extended hand drill, b) Exposure of the sella dura; the arrow indicates the dura mater

References

-

Aboud E, Al-Mefty O, Yaşargil MG. New laboratory model for neurosurgical training that simulates live surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(6):1367–72. doi:10.3171/jns.2002.97.6.1367.

-

Hicdönmez T, Birgili B, Tiryaki M, Parsak T, Çobanoğlu S. Posterior fossa approach: microneurosurgical training model in cadaveric sheep. Turk Neurosurg. 2006;16:111–4.

-

Korotkov D, Abramyan A, Wuo-Silva R, Chaddad-Neto F. Cadaveric sheep head model for anterior clinoidectomy in neurosurgical training. World Neurosurg. 2023;175:481–91. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2023.03.129.

-

Dalgic A, Caliskan M, Can P, et al. Experimental endoscopic cordotomy in the sheep model. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26(2):286-90. doi:10.5137/1019-5149. JTN.12229-14.1

-

Korotkov DS, Paitán AF, Abramyan A, Chaddad Neto FEA. Sheep head cadaveric model for the transmeatal extensions of the retrosigmoid approach. Asian J Neurosurg. 2024;19(4):791–804. doi:10.1055/s-0044-1790517

-

Onoda K, Fujiwara R, Sashida R, et al. In vivo goat brain model for neurosurgical training. Surg Neurol Int. 2022;13:344. doi:10.25259/SNI_494_2022.

-

Stan C, Ujvary LP, Blebea CM, et al. Sheep’s head as an anatomic model for basic training in endoscopic sinus surgery. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(10):1792. doi:10.3390/medicina59101792.

-

Grist EP. Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy risk assessment: the UK experience. Risk Anal. 2005;25(3):519–32. doi:10.1111/j.1539- 6924.2005.00619.x.

-

Rhoton AL Jr. The anterior and middle cranial base. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(Suppl 4):S273–302.

-

Gélinas-Phaneuf N, Del Maestro RF. Surgical expertise in neurosurgery: integrating theory into practice. Neurosurgery. 2013;73(Suppl 1):30–8. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000115.

-

Liu JK, Kshettry VR, Recinos PF, Kamian K, Schlenk RP, Benzel EC. Establishing a surgical skills laboratory and dissection curriculum for neurosurgical residency training. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(5):1331–8. doi:10.3171/2014.11.JNS14902.

-

Sahoo SK, Gupta SK, Salunke P, et al. Setting up a neurosurgical skills laboratory and designing simulation courses to augment resident training program. Neurol India. 2022;70(2):612–7. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.344633.

-

Abecassis IJ, Sen RD, Ellenbogen RG, Sekhar LN. Developing microsurgical milestones for psychomotor skills in neurological surgery residents as an adjunct to operative training: the home microsurgery laboratory. J Neurosurg. 2020;135(1):194–204. doi:10.3171/2020.5.JNS201590.

-

Ahumada-Vizcaino JC, Wuo-Silva R, Hernández MM, Chaddad-Neto F. The art of combining neuroanatomy and microsurgical skills in modern neurosurgery. Front Neurol. 2023;13:1076778. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.1076778.

-

Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 Suppl):S70–81. doi:10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022.

-

Gholami S, Manon A, Yao K, Billard A, Meling TR. An objective skill assessment framework for microsurgical anastomosis based on ALI scores. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2024;166(1):104. doi:10.1007/s00701-024-05934-1.

-

Koskinen J, Huotarinen A, Elomaa AP, Zheng B, Bednarik R. Movement-level process modeling of microsurgical bimanual and unimanual tasks. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2022;17(2):305–14. doi:10.1007/s11548-021-02537-4.

-

Satava RM. Historical review of surgical simulation--a personal perspective. World J Surg. 2008;32(2):141–8. doi:10.1007/s00268-007-9374-y.

-

Rosen JM, Long SA, McGrath DM, Greer SE. Simulation in plastic surgery training and education: the path forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(2):729–38. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181958ec4.

-

Chawla S, Devi S, Calvachi P, Gormley WB, Rueda-Esteban R. Evaluation of simulation models in neurosurgical training accordingly to face, content, and construct validity: a systematic review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2022;164(4):947–66. doi:10.1007/s00701-021-05003-x.

-

Ghosh SK. Cadaveric dissection as an educational tool for anatomical sciences in the 21st century. Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10(3):286–99. doi:10.1002/ase.1649.

-

Brewin J, Nedas T, Challacombe B, Elhage O, Keisu J, Dasgupta P. Face, content and construct validation of the first virtual reality laparoscopic nephrectomy simulator. BJU Int. 2010;106(6):850–4. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09193.x.

-

Jones DG, Whitaker MI. Engaging with plastination and the Body Worlds phenomenon: a cultural and intellectual challenge for anatomists. Clin Anat. 2009;22(6):770–6. doi:10.1002/ca.20824.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ankara Education and Research Hospital Animal Experiments (Date: 2024-11-01, No: 799)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Ömer Şahin. Using cadaveric sheep head models for transnasal transsphenoidal pituitary surgery training in neurosurgery. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(1):39-42

Publication History

- Received:

- March 27, 2025

- Accepted:

- May 12, 2025

- Published Online:

- May 29, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026