Shock indices for predicting adverse clinical outcomes in hypertensive acute pulmonary edema

Shock indices in hypertensive pulmonary edema

Authors

Abstract

Aim Shock indices (SI, MSI, aSI) are established in trauma and sepsis. Because hemodynamic derangements drive hypertensive acute pulmonary edema (HAPE), these simple, bedside metrics may aid early risk assessment. We evaluated their association with adverse clinical outcomes (ACOs) in HAPE.

Materials and Methods Adults with HAPE presenting to a tertiary emergency department between 1 May and 31 October 2024 (n = 129) were included. Predefined ACOs were hospital admission, prolonged hospitalization, and need for high-dose intravenous furosemide/nitroglycerin. Indices were calculated from triage vitals, and discrimination was assessed by ROC analysis with pairwise AUC comparisons (α = 0.05).

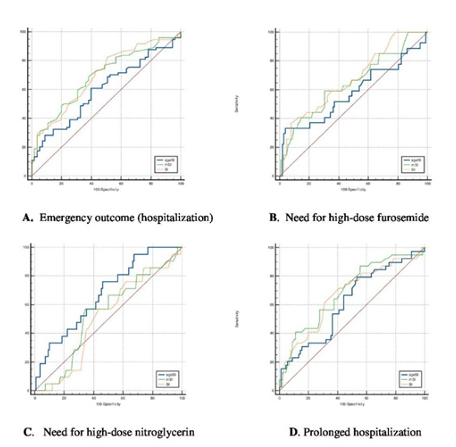

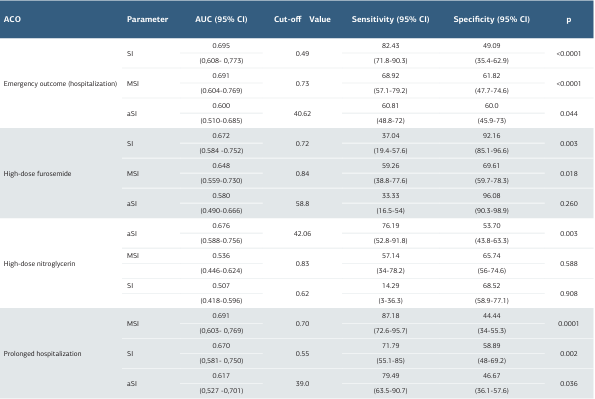

ResultsFor hospital admission, SI (cut-off > 0.49, AUC = 0.695, p < 0.0001) and MSI (cut-off > 0.73, AUC = 0.691, p < 0.0001) showed moderate discrimination; aSI was significant with lower accuracy (cut-off > 40.62, AUC = 0.600, p = 0.044). For high-dose furosemide, SI (cut-off > 0.72, AUC = 0.672, p = 0.003) and MSI (cut-off > 0.84, AUC = 0.648, p = 0.018) were significant. For high-dose nitroglycerin, only aSI was significant (cut-off > 42.06, AUC = 0.676, p = 0.003). For prolonged hospitalization, SI (cut-off > 0.55, AUC = 0.670, p = 0.002), MSI (cut-off > 0.70, AUC = 0.691, p = 0.0001), and aSI (cut-off > 39.0, AUC = 0.617, p = 0.036) were significant; MSI outperformed aSI.

Discussion SI and MSI were significant predictors of hospital admission (cut-off > 0.49, AUC = 0.695; cut-off > 0.73, AUC = 0.691; respectively), high-dose furosemide use (cut-off > 0.72, AUC = 0.672; cut-off > 0.84, AUC = 0.648), and prolonged hospitalization (cut-off > 0.55, AUC = 0.670; cut-off > 0.70, AUC = 0.691), whereas aSI was significant for high-dose nitroglycerin requirement (cut-off > 42.06, AUC = 0.676). However, given their generally moderate AUCs and variable sensitivity–specificity profiles, they should be interpreted alongside clinical, vital, and laboratory findings rather than used in isolation. Validation through larger, prospective, multicenter studies is warranted.

Keywords

Introduction

Acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema (ACPE) is a clinical condition that may occur following major cardiac events such as myocardial infarction, hypertensive crisis, or acute decompensation of heart failure. It is characterized by sudden fluid accumulation in the lungs due to impaired systolic or diastolic function of the left ventricle (LV), often leading to respiratory failure [1–3]. In the emergency department (ED), management of ACPE relies on rapid assessment of the patient’s hemodynamic status, as early recognition of hemodynamic compromise plays a critical role in treatment success [1]. Otherwise, multiorgan failure and a high risk of mortality may ensue [4].

The Shock Index (SI), calculated as the ratio of heart rate to systolic blood pressure (SBP), is a simple and rapid marker for assessing cardiac function. It is widely used to evaluate hemodynamic stability in patients with acute cardiovascular events [5]. The Modified Shock Index (MSI), which incorporates mean arterial pressure (MAP), provides a more refined assessment and is considered particularly sensitive in conditions where blood pressure fluctuations are frequent [6]. The Age Shock Index (aSI), by integrating age, offers greater reliability in evaluating the severity of shock, especially in older patients. Indeed, the literature reports that aSI outperforms traditional shock indices in predicting complications among trauma patients [7] and in determining long-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction [8].

In this context, evaluating hemodynamic markers in ACPE patients requiring rapid management in the ED is crucial for preventing adverse clinical outcomes (ACO). The aim of our study was to assess the effectiveness of shock indices in predicting ACO among patients presenting with the hypertensive acute pulmonary edema (HAPE) phenotype of ACPE.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was conducted through a retrospective analysis of data from patients presenting to the adult ED of a university hospital.

Inclusion Criteria

Between May 1 and October 31, 2024, patients ≥18 years of age who presented to the adult ED of Mersin University Faculty of Medicine Hospital with acute (≤48 hours) respiratory distress, preserved LV function, SBP ≥140 mmHg at admission, physical examination and chest imaging findings consistent with pulmonary edema, and a diagnosis of HAPE [9], with complete data sets, were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

During the study period, patients presenting with other phenotypes of ACPE—namely those who were normotensive or hypotensive at admission (SBP <140 mmHg) or met criteria for cardiogenic shock (SBP <90 mmHg with signs of hypoperfusion and/or vasopressor requirement) [9]—were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria were respiratory distress attributed to causes other than ACPE, ongoing dialysis therapy, pregnancy, incomplete data sets, and age under 18 years.

Data Analysis

Demographic and clinical data of the patients were evaluated. SI was defined as the ratio of heart rate to SBP (mmHg); MSI as the ratio of heart rate to MAP (mmHg); and aSI as the product of SI and age. In this study, these indices were retrospectively calculated based on the vital signs recorded at ED admission. ED outcomes were defined as discharge from the ED or hospitalization (ward or intensive care unit). Treatments administered for HAPE included intravenous (IV) furosemide, nitroglycerin, noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV), digoxin, morphine, hemodialysis, and intubation. IV furosemide and nitroglycerin doses were calculated on an ampoule basis (1 ampoule furosemide = 20 mg; 1 ampoule nitroglycerin = 10 mg).

The total length of hospital stay (including ED and/or hospitalization) and the mean doses of IV furosemide and nitroglycerin administered during this period were recorded. A hospital stay longer than the mean duration was defined as prolonged hospitalization, while doses above the mean were considered as high-dose symptomatic treatment requirements. These thresholds were derived from the mean values of the study population and were considered clinically arbitrary.

ACO was defined as the need for hospitalization from the ED, prolonged hospital stay among admitted patients, or the requirement for high-dose IV furosemide or nitroglycerin therapy.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables were presented as median [interquartile range]. Categorical variables were summarized as numbers and percentages (%). Comparisons of mean values between ED outcome groups were performed using the Student’s t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann–Whitney U test for non- normally distributed data. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was applied to evaluate the performance of shock indices in predicting ACO. Pairwise comparisons were performed to assess the discriminatory performance of indices for different clinical outcomes, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for differences in the areas under the curve (AUC). For AUC, the following interpretation was used: 0.50– 0.59, poor; 0.60–0.69, moderate; 0.70–0.79, acceptable/good; 0.80–0.89, very good; and ≥0.90, excellent. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mersin University Rectorate (Date: 2024-11-27, No: 1166).

Results

A total of 129 adult patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Of these, 55% were female, and the mean age of all patients was 73.62 ± 12.01 years. While 42.6% of cases were discharged from the ED, 57.4% required hospitalization (17.8% ward, 39.5% intensive care unit). No mortality occurred in the ED; however, mortality was observed in 18.9% of hospitalized patients (10.9% of all cases) (p = 0.001).

A history of at least one chronic disease was present in 91.5% of patients. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (84.5%), diabetes mellitus (51.9%), coronary artery disease (51.9%), and congestive heart failure (32.6%). No statistically significant differences were found in the distribution of comorbidities between discharged and hospitalized groups.

The most commonly used medications were antihypertensives (76.7%), antiplatelets (50.4%), and diuretics (48.8%), followed by beta-blockers (28.7%) and novel oral anticoagulants (14.7%). Warfarin use was higher among discharged patients compared to those who were hospitalized (7.3% vs. 0%, p = 0.031).

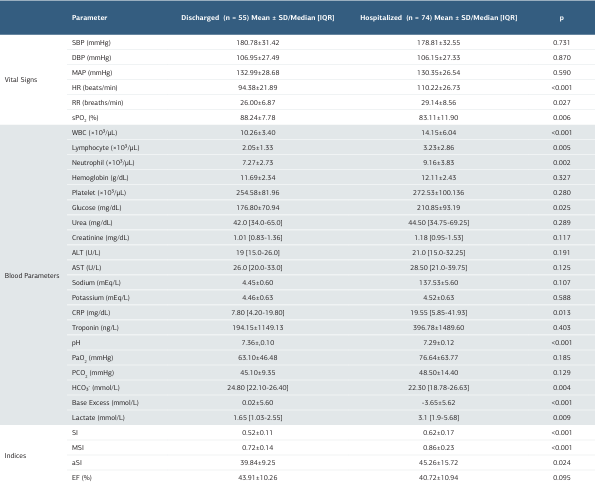

When ED outcome groups were compared, hospitalized patients had significantly higher heart rate (p < 0.001) and respiratory rate (p = 0.027), while oxygen saturation was significantly lower (p = 0.006). In addition, leukocyte (p < 0.001), lymphocyte (p = 0.005), neutrophil (p = 0.002), glucose (p = 0.025), C-reactive protein (p = 0.013), and lactate (p = 0.009) levels were significantly higher in this group, whereas pH (p < 0.001), bicarbonate (p = 0.004), and base excess (p < 0.001) values were significantly lower. The mean SI (p < 0.001), MSI (p < 0.001), and aSI (p = 0.024) were also significantly higher among hospitalized patients (Table 1).

Endotracheal intubation was required in 3.1% of cases and hemodialysis in 2.3%, despite treatment. All patients received IV furosemide, while 82.9% received IV nitroglycerin, 81.4% NIMV, 6.2% sublingual nitrate, 2.3% digoxin, and 1.6% morphine.

Comparison between groups revealed significant differences in the use of NIMV and furosemide, both being more frequently administered in hospitalized patients (NIMV: 67.3% vs. 90.5%, p = 0.001; furosemide: 7 [7–11] ampoules vs. 12 [7–19] ampoules, p < 0.001).

Evaluation of the Performance of Indices for ED Outcomes ROC analysis demonstrated that all indices were significant in predicting the need for hospitalization. SI (cut-off > 0.49, AUC = 0.695, p < 0.0001) and MSI (cut-off > 0.73, AUC = 0.691, p < 0.0001) showed moderate discriminatory power, whereas aSI (cut-off > 40.62, AUC = 0.600, p = 0.044) exhibited lower performance.

In pairwise comparisons, aSI was significantly inferior to both SI (AUCaSI–SI = 0.0950, p = 0.003) and MSI (AUCaSI–MSI = 0.0908, p = 0.009), while no significant difference was observed between SI and MSI (AUCMSI–SI = 0.0041, p = 0.855) (Table 2, Figure 1A).

Evaluation of the Performance of Indices in Predicting the Need for High-Dose Furosemide Therapy The mean total dose of furosemide administered was 16.61 ± 22.49 ampoules. According to ROC analysis, SI (cut-off > 0.72, AUC = 0.672, p = 0.003) and MSI (cut-off > 0.84, AUC = 0.648, p = 0.018) demonstrated moderate discriminatory power in predicting the need for high-dose furosemide. In contrast, aSI (cut-off > 58.8, AUC = 0.580, p = 0.260) did not show significant performance.

In pairwise comparisons, aSI was significantly inferior to SI (AUCaSI–SI = 0.0920, p = 0.033), while no significant differences were observed between aSI and MSI or between MSI and SI (AUCaSI–MSI = 0.0677, p = 0.132; AUCMSI–SI = 0.0243, p = 0.278) (Table 2, Figure 1B).

Evaluation of the Performance of Indices in Predicting the Need for High-Dose Nitroglycerin Therapy

The mean total dose of nitroglycerin administered was 1.56 ± 3.76 ampoules. According to ROC analysis, SI (cut-off > 0.62, AUC = 0.507, p = 0.908) and MSI (cut-off > 0.83, AUC = 0.536, p = 0.588) were not significant in predicting the need for high- dose nitroglycerin therapy. In contrast, aSI (cut-off > 42.06, AUC = 0.676, p = 0.003) showed statistically significant performance with moderate discriminatory power (Table 2, Figure 1C).

Evaluation of the Performance of Indices in Predicting the Need for Prolonged Hospitalization

The mean length of stay was calculated as 73.12 ± 121.60 hours. According to ROC analysis, MSI (cut-off > 0.70, AUC = 0.691, p = 0.0001), SI (cut-off > 0.55, AUC = 0.670, p = 0.002), and aSI (cut-off > 39.0, AUC = 0.617, p = 0.036) were all significant in predicting the need for prolonged hospitalization. SI and MSI demonstrated moderate discriminatory power, whereas aSI showed lower performance.

In pairwise comparisons, a significant difference was observed only between aSI and MSI (AUCaSI–MSI = 0.0741, p = 0.037; AUCaSI–SI = 0.0528, p = 0.111; AUCMSI–SI = 0.0212, p = 0.341) (Table 2, Figure 1D).

Discussion

Early recognition of patients with HAPE and rapid identification of those at high risk are of critical importance for ED clinicians. Shock indices have long been used in conditions with high mortality risk, such as sepsis, trauma, and myocardial infarction, due to their prognostic value. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the effectiveness of shock indices in predicting ACO among patients presenting to the ED with HAPE within the same analysis. Our findings suggest that integrating shock indices into the initial assessment process may be clinically beneficial, particularly in EDs with limited resources or high patient volumes. This approach can help clinicians rapidly stratify patients according to hemodynamic risk, facilitate early recognition and triage of high-risk cases, and identify those likely to require acute or prolonged hospitalization in advance. Consequently, it may enable more efficient utilization of critical care resources and improve overall preparedness. Furthermore, shock indices may serve as supportive tools in clinical management by assisting in confirming patients who may require high-dose furosemide or nitroglycerin therapy, guiding early treatment decisions, and distinguishing cases that may need therapeutic escalation.

In our study, more than half of the patients presenting to the ED required hospitalization, and the in-hospital mortality rate among hospitalized patients was 18.9%. Similarly, the literature reports an in-hospital mortality rate of 15–20% in patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema, with long-term (6- year) mortality rates reaching up to 85% [10, 11]. In light of these data, the use of easily calculable shock indices in patients presenting with HAPE may serve as a complementary tool for clinical assessment, facilitating early triage, timely initiation of appropriate treatment strategies, and prediction of ACO.

Our analysis revealed that all shock indices were statistically significant predictors of hospitalization and prolonged hospital stay. For hospitalization decisions, SI showed moderate discriminatory power with particularly high sensitivity, whereas MSI was more prominent in predicting prolonged hospitalization. There is a substantial body of literature investigating the prognostic value of shock indices for predicting ACOs across different clinical settings and diverse patient populations. Rady et al. [12] reported that SI was superior to conventional vital signs in identifying critical illness and intensive care unit admission, while Kocaoğlu et al. [13] noted that SI was stronger than MSI/ aSI in predicting hospitalization and mortality among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Prasad et al. [14] emphasized that in septic patients admitted from the ED, SI demonstrated superior predictive ability for mechanical ventilation requirements compared with MSI and aSI. Furthermore, a 2023 study by Hamade et al. [15] showed that in an unselected adult ED population, MSI > 1.7 predicted both hospital admission and in-hospital mortality, supporting its potential use in early triage and disposition decisions. Similarly, Liao et al. [16] reported that in trauma patients, SI and MSI predicted mortality and transfusion needs and facilitated ED to intensive care unit transfer decisions, further confirming— consistent with our findings—the prognostic utility of these indices for ACOs. Furthermore, Lee et al. [17] emphasized the potential clinical utility of aSI in high-risk patients, highlighting its superior performance in predicting post-intubation hypotension. Our findings suggest that these indices, which reflect hemodynamic instability and can be rapidly calculated, may serve as decision-support tools in patients presenting with HAPE, both for identifying severe clinical presentations requiring hospitalization and for early prediction of prolonged hospital stay.

It was observed that SI and MSI showed statistically significant performance in predicting the need for high-dose furosemide. While SI showed low sensitivity but high specificity, this suggests that a positive SI may help confirm the requirement for high-dose furosemide, though it may not be sufficient as a standalone tool for exclusion. Felker et al. [18] reported that the use of high-dose diuretics in acute decompensated heart failure was associated with worsening renal function; in this context, SI may provide clinical utility in identifying the high-risk subgroup likely to require treatment escalation. On the other hand, Pourafkari et al. [19] emphasized that SI and MSI alone were insufficient as prognostic factors for in-hospital outcomes in acute heart failure, while aSI could enhance predictive accuracy. Therefore, the indices evaluated in our study should be validated in future research.

We found that only aSI demonstrated statistically significant performance in predicting the need for high-dose nitroglycerin. Although studies directly linking shock indices with nitroglycerin dosing are limited, our findings are consistent with reports emphasizing the importance of nitrates as vasodilator therapy in the management of cardiogenic pulmonary edema [20] and with studies reporting the prognostic value of SI, MSI, and aSI in acute heart failure [21]. The inclusion of age in aSI likely enables better reflection of hemodynamic compromise, particularly in elderly or frail patients. However, its relatively low specificity and only moderate discriminatory power suggest that aSI should be regarded as a supportive measure in clinical decision-making for high-dose nitroglycerin, rather than as a sole determinant.

Finally, the thresholds defining high-dose treatment and prolonged hospitalization in our study were derived from the mean values of the study population. Variations in clinical workload, prolonged ED boarding times due to hospital capacity, and differences in physician decision-making that may influence treatment intensity or hospitalization duration contributed to the study-specific nature of these thresholds. Therefore, these cut-off values should not be interpreted as universal clinical criteria across different patient populations or healthcare settings.

Limitations

This study was retrospective and single-center, with a limited sample size. The operational definition of the HAPE phenotype and the single-time recording of variables (e.g., initial vital signs) may have introduced measurement bias and potential phenotype misclassification. The non-standardized use of treatment approaches (furosemide/nitrate/NIMV) and chronic rate-controlling medications may also have influenced vital signs and, consequently, SI/MSI/aSI calculations. Additionally, ED-specific doses were not analyzed separately because variable ED stay durations — often prolonged due to cardiology ward or intensive care unit bed unavailability — could have biased dose comparisons. Our findings should therefore be validated in larger, prospective, multicenter studies.

Conclusion

Rapid assessment of hemodynamic parameters and related shock indices in the ED is important for preventing ACO in patients with HAPE. In our study, when comparing the performance of the indices, SI provided moderate discriminatory power with higher sensitivity for hospitalization decisions, whereas MSI demonstrated greater sensitivity in predicting prolonged hospital stay. For high-dose furosemide, the low sensitivity but higher specificity profile of SI suggests that it may support clinical evaluation in identifying patients with an increased likelihood of requiring high doses, though it is not sufficient as a sole determinant of dosing decisions. In predicting the need for high-dose nitroglycerin, only aSI was significant; however, its relatively low specificity and moderate discriminatory power indicate that aSI should be considered an adjunctive measure in clinical assessment.

Overall, shock indices demonstrated moderate predictive power in patients presenting with HAPE and emerged as practical markers contributing to clinical decision-making during the initial assessment. However, these measures should not be used in isolation; they must be interpreted alongside clinical, vital, and laboratory findings, and our results require validation through larger, prospective, multicenter studies.

Figures

Figure 1. Figure A illustrates the ROC curves of the indices in predicting hospitalization, figure B presents the ROC curves for predicting the need for high-dose furosemide, figure C shows the ROC curves for predicting the need for high-dose nitroglycerin, figure D displays the ROC curves for identifying patients requiring prolonged hospitalization

Tables

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients presenting with hypertensive acute pulmonary edema (HAPE)

SD: Standard deviaton; IQR: Interquartile Range [%25-%75]; SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure, DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure, MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure, HR: Heart Rate, RR: Respiratory Rate, SpO₂ (%): Peripheral Oxygen Saturation, WBC: White Blood Cell Count, ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase, CRP: C-Reactive Protein, PaO₂: Partial Pressure of Oxygen, PaCO₂: Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide, HCO₃⁻: Bicarbonate, SI: Shock Index, MSI: Modified Shock Index, aSI: Age-Shock Index, EF: Ejection Fraction

Table 2. The performance of shock indices in predicting adverse clinical outcomes in patients presenting with hypertensive acute pulmonary edema (HAPE)

ACO: Adverse Clinical Outcome, AUC: Area Under the Curve, CI: Confidence Interval, SI: Shock Index, MSI: Modified Shock Index, aSI: Age Shock Index

References

-

Mebazaa A, Tolppanen H, Mueller C, et al. Acute heart failure and cardiogenic shock: a multidisciplinary practical guidance. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(2):147- 63.

-

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891-975.

-

Harjola VP, Mebazaa A, Čelutkienė J, et al. Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(3):226-41.

-

Lavignasse D, Lemoine S, Karam N, et al. Does age influence out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcomes among women? Insights from the Paris SDEC. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022;11(4):293-302.

-

Devendra Prasad KJ, Abhinov T, Himabindu KC, Rajesh K, Krishna Moorthy D. Modified shock index as an indicator for prognosis among sepsis patients with and without comorbidities presenting to the emergency department. Cureus. 2021;13(12):e20283.

-

Yu T, Tian C, Song J, He D, Sun Z, Sun Z. Age shock index is superior to shock index and modified shock index for predicting long-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction. Shock. 2017;48(5):545-50.

-

Rau CS, Wu SC, Kuo SC, et al. Prediction of massive transfusion in trauma patients with shock index, modified shock index, and age shock index. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7):683.

-

Zarzaur BL, Croce MA, Fischer PE, Magnotti LJ, Fabian TC. New vitals after injury: shock index for the young and age x shock index for the old. J Surg Res. 2008;147(2):229-36.

-

Filippatos G, Zannad F. An introduction to acute heart failure syndromes: definition and classification. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12(2):87-90.

-

Crane SD. Epidemiology, treatment, and outcome of acidotic, acute, cardiogenic pulmonary oedema presenting to an emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2002;9(4):320-24.

-

Wiener RS, Moses HW, Richeson JF, Gatewood RP Jr. Hospital and long-term survival of patients with acute pulmonary edema associated with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(1):33-5.

-

Rady MY, Smithline HA, Blake H, Nowak R, Rivers E. A comparison of the shock index and conventional vital signs to identify acute, critical illness in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24(4):685-90. Erratum in: Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24(6):1208.

-

Kocaoglu S, Karadas A. Comparison of the effectiveness of shock index, modified shock index, and age shock index in COPD exacerbations. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2022;32(9):1187-90.

-

Prasad KJD, Bindu KCH, Abhinov T, Moorthy K, Rajesh K. A comparative study on predictive validity of modified shock index, shock index, and age shock index in predicting the need for mechanical ventilation among sepsis patients in a tertiary care hospital. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2023;16(1):17-21.

-

Hamade B, Bayram JD, Hsieh YH, Khishfe B, Al Jalbout N. Modified shock index as a predictor of admission and in-hospital mortality in emergency departments; an analysis of a US national database. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2023;11(1):e34.

-

Liao TK, Ho CH, Lin YJ, Cheng LC, Huang HY. Shock index to predict outcomes in patients with trauma following traffic collisions: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2024;50(5):2191-8.

-

Lee K, Jang JS, Kim J, Suh YJ. Age shock index, shock index, and modified shock index for predicting postintubation hypotension in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(5):911-5.

-

Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, et al. Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):797-805.

-

Pourafkari L, Wang CK, Schwartz M, Nader ND. Does shock index provide prognostic information in acute heart failure? Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:140-2.

-

Zanza C, Saglietti F, Tesauro M, et al. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema in emergency medicine. Adv Respir Med. 2023;91(5):445-63.

-

Castillo Costa Y, Cáceres L, Mauro V, et al. Shock index, modified shock index, and age-adjusted shock index as predictors of in-hospital death in acute heart failure. Sub-analysis of the Argen-IC. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47(10):101309.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mersin University Rectorate (Date: 2024-11-27, No: 1166)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Musa Bakış, Çağrı Safa Buyurgan, Akif Yarkaç, Seyran Bozkurt, Ataman Köse, Gülhan Orekici Temel. Shock indices for predicting adverse clinical outcomes in hypertensive acute pulmonary edema. Ann Clin Anal Med 2025;16(12):899-904

Publication History

- Received:

- September 26, 2025

- Accepted:

- November 24, 2025

- Published Online:

- November 27, 2025

- Printed:

- December 1, 2025