Relationship between umbilical cord coiling index and umbilical artery doppler S/D ratio in high-risk pregnancies

Relationship between UCI and umbilical artery doppler

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the postnatally measured umbilical cord coiling index (UCI) and the antenatally assessed umbilical artery (UA) Doppler systolic/diastolic (S/D) ratio in high-risk pregnancies.

Methods A total of 491 singleton pregnancies over 24 weeks of gestation were evaluated. Participants were divided into two groups. The UA S/D ratio was measured in the antenatal period for all cases. After delivery, UCI values were calculated. Based on UCI values, cases were categorized as hypocoiled, normocoiled, and hypercoiled.

Results In the high-risk pregnancy group, fetal birth weight was lower, and the UA S/D ratio was significantly higher (p < 0.01). The mean UCI values were calculated. No statistically significant correlation was observed between UCI and UA S/D ratio overall. A significant difference was found between the type of delivery and UCI categories; vaginal deliveries were more common in the control group (p < 0.01), while there was no significant difference between groups in terms of cesarean section rates (p = 0.32). No significant difference was observed between groups in neonatal intensive care unit admission rates (p = 0.414).

Conclusion UCI may be associated with the type of delivery and certain perinatal outcomes. As there are limited studies on this subject in the literature, more comprehensive and prospective studies are needed to evaluate the feasibility of using UCI in routine antenatal screening.

Keywords

Introduction

The umbilical cord is the primary structure that facilitates gas exchange and nutrient transport between the fetus and the placenta. The spiral arrangement of the two umbilical arteries and one umbilical vein within the cord not only enhances its structural durability but also provides resistance against mechanical pressure during labor.1 This spiral configuration of the umbilical cord is referred to as “coiling” and is numerically expressed by the cord coiling index (UCI). UCI is a parameter calculated by dividing the total number of coils by the length of the cord in centimeters.2

Values of UCI outside the physiological range (normocoiling) are defined as hypocoiling ( < 0.1 coil/cm) or hypercoiling ( > 0.3 coil/cm), and have been associated with various obstetric and neonatal complications. Hypocoiling is linked to decreased mechanical protection of umbilical vessels, while hypercoiling has been associated with increased vascular resistance and circulatory disturbances.3,4 Studies have shown that abnormal UCI values may be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as fetal growth restriction (FGR), preterm birth, fetal distress, low APGAR scores, and increased cesarean delivery rates.5,6,7

Doppler ultrasonography is a widely used method for assessing fetal well-being. Umbilical artery (UA) Doppler measurements provide insight into placental vascular resistance and are used as a prognostic tool, particularly in the management of high-risk pregnancies.8An increase in the UA Doppler Systole/Diastole (S/D) ratio may indicate impaired uteroplacental perfusion and the development of fetal hypoxia.9 It is particularly recommended to monitor UA S/D ratios carefully in high-risk pregnancies such as those complicated by FGR, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).10

There are only a limited number of studies investigating the possible relationship between UCI and UA Doppler findings. While De Laat et al. suggested that abnormal UCI might affect uteroplacental circulation, Ernst et al. indicated that hypercoiled cords may negatively influence vascular circulation.11,12 To the best of our knowledge, there is no clear consensus in the literature regarding a significant correlation between UCI and Doppler parameters. This raises questions about UCI’s potential to predict fetal risks antenatally and its applicability in clinical practice.

In this context, our study aims to investigate the relationship between UCI measured postpartum and the UA Doppler S/D ratio assessed prenatally in high-risk pregnancies. Additionally, by examining the association between UCI and perinatal outcomes such as type of delivery, gestational age at birth, birth weight, and APGAR score, we aim to determine the diagnostic and prognostic value of UCI in clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

In total, 500 singleton pregnancies beyond 24 weeks of gestation were included in the study. The patients were divided into two groups: 250 patients with high-risk pregnancies (complicated by preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction (FGR), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), or oligohydramnios) and 250 patients with uncomplicated pregnancies. Nine patients from the high-risk group were excluded from the study due to the absence of diastolic flow in the umbilical artery (UA) Doppler measurements, which made it impossible to calculate the S/D ratio. The following cases were also excluded from the study: maternal anemia, Rh incompatibility, maternal chronic and congenital diseases, body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2, deliveries before 24 weeks of gestation, multiple pregnancies, placental cord insertion anomalies, fetal congenital anomalies, cord knots, and single umbilical artery.

UA Doppler S/D measurements (performed within one week prior to delivery) and postpartum UCI measurements were conducted by the same obstetrician. The following variables were recorded for all patients: maternal age, parity, hemogram values, blood group, gestational age, UA Doppler S/D ratio, type of delivery (cesarean or vaginal birth), maternal and fetal complications (such as preeclampsia, FGR, GDM, oligohydramnios), newborn birth weight, sex, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, number of umbilical cord coils, cord length, and 5-minute APGAR score. Immediately after delivery, the umbilical cord was clamped approximately 5 cm from the fetal end and carefully cut with scissors without milking the cord. The placenta was delivered with active management. The length of the cord from the cut end to the placental insertion was measured with a measuring tape, and 5 cm was added to this length. The total number of coils was counted, and the UCI was calculated by dividing this number by the total cord length. UA Doppler S/D measurements were performed and recorded using a GE Healthcare Voluson E6 ultrasound device.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Van Yuzuncu Yil University (Date: 2022-06-13, No: 07).

Statistical Analysis

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7) to determine the sensitivity of the study for detecting mean differences between two independent groups. Assuming a two-tailed independent samples t-test with an alpha level of 0.05 and a desired statistical power of 0.80, the available sample sizes of 250 and 241 participants per group indicated that the study was adequately powered to detect a minimum effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.25. Normality of distribution for continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (for n > 50) and Skewness-Kurtosis values. As the data were normally distributed, parametric tests were applied. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were expressed as mean, standard deviation (SD), number (n), and percentage (%). Differences between measurement values between categorical groups were analyzed using the independent sample t-test, and ANOVA was used to compare more than two groups. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess relationships between continuous variables. For associations between categorical variables, the Chi-square test was used. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS for Windows, version 26, Armonk, New York: IBM Corp.).

Reporting Guidelines

This study was reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines.

Results

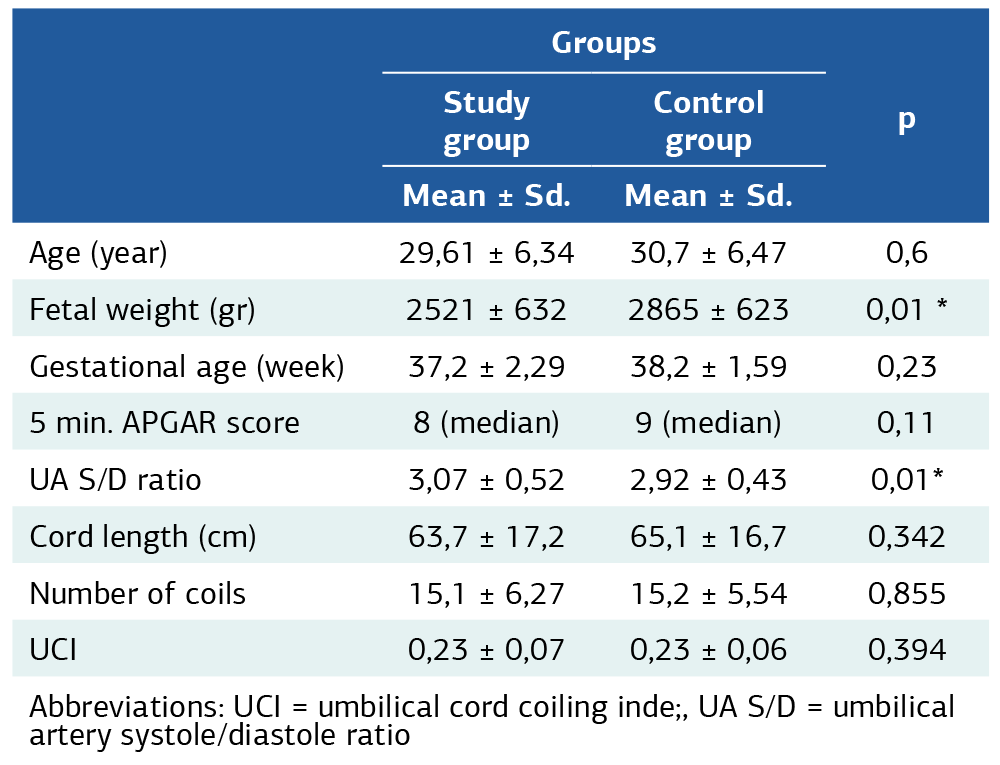

A total of 491 patients were included in the study. Among the participants, 241 had high-risk pregnancies, while 250 had uncomplicated pregnancies without any additional risk factors. The mean maternal age was 29.61 ± 6.34 years in the study group and 30.7 ± 6.47 years in the control group, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.6). The mean fetal birth weight was calculated as 2521 ± 632 grams in the study group and 2865 ± 623 grams in the control group, and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.01). The mean gestational age at delivery was 37.2 ± 2.29 weeks in the study group and 38.2 ± 1.59 weeks in the control group; however, there was no statistically significant difference between the gestational ages (p = 0.23). There was no significant difference in the median 5-minute Apgar scores between the groups (8 vs 9, p = 0.11). The mean umbilical artery (UA) S/D ratio was 3.07 ± 0.52 in the study group and 2.92 ± 0.43 in the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of coil length, number of coils, or UCI values (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

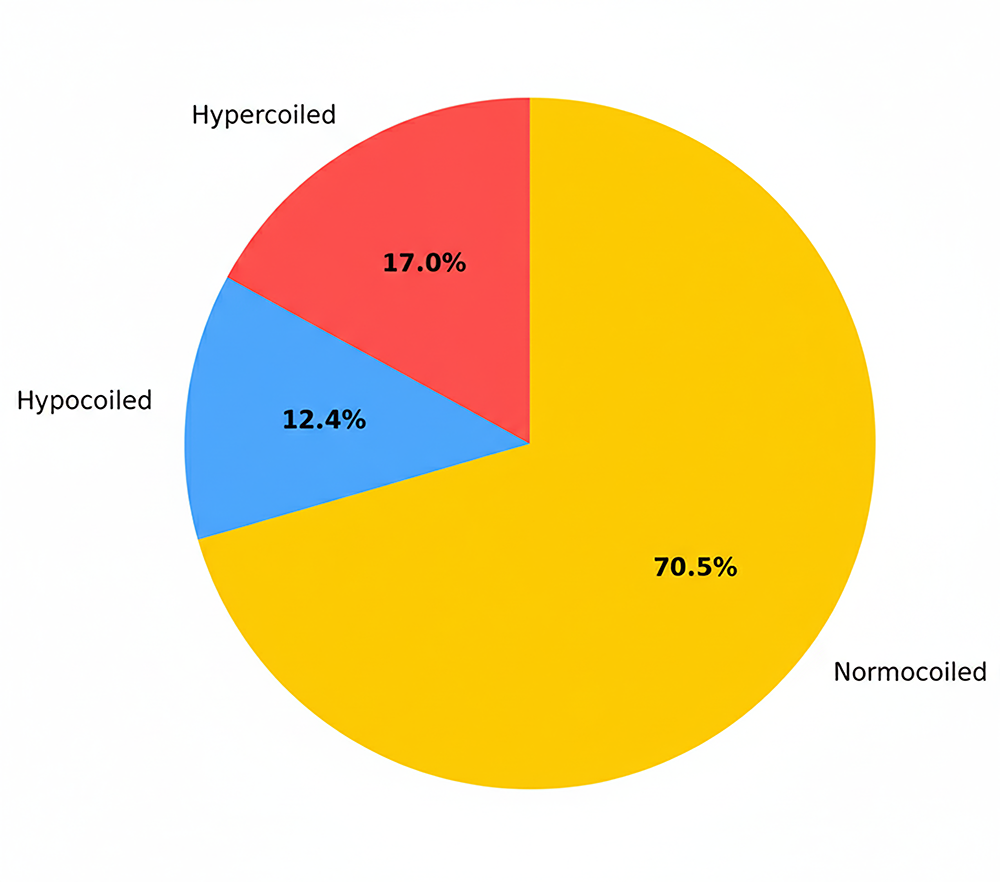

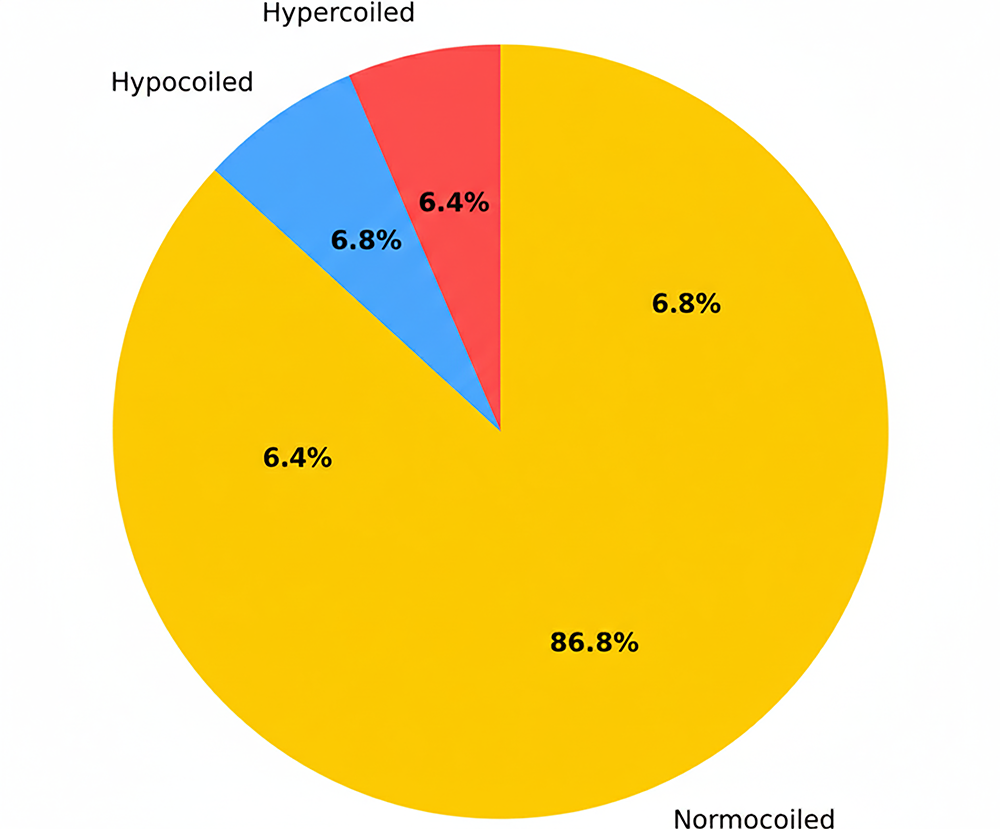

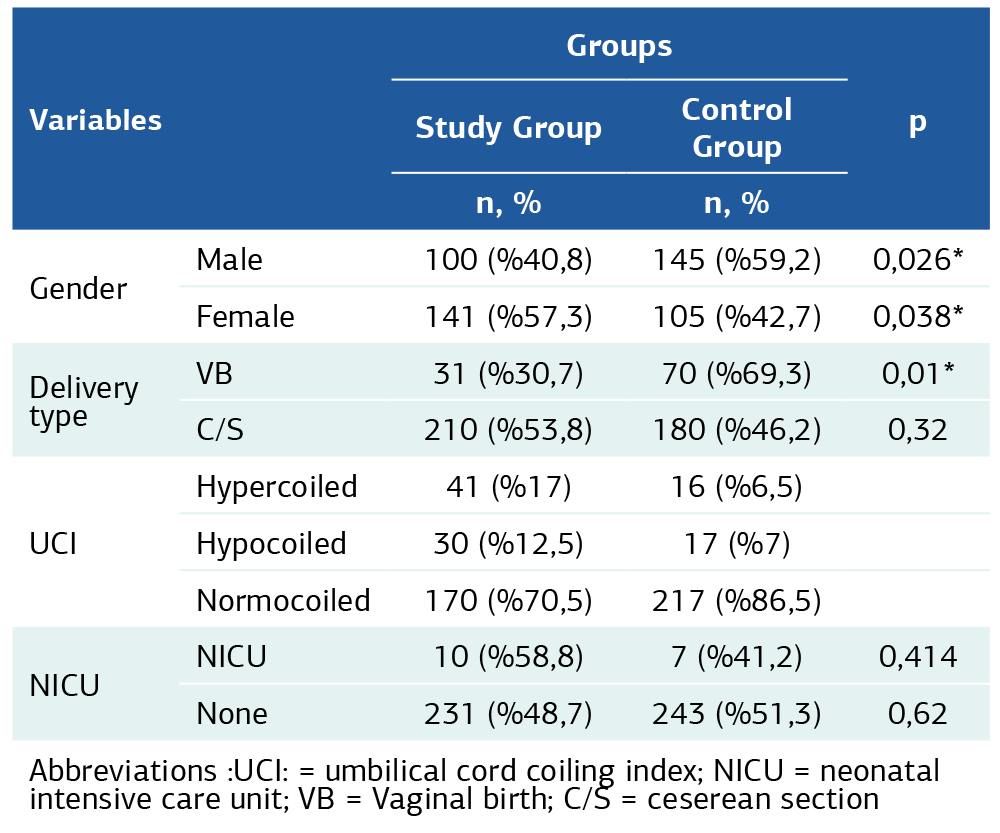

In the control group, the number of male infants was significantly higher (n = 145, 59.2% vs. n = 100, 40.8%), and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.026). In the study group, the number of female infants was higher (n = 141, 57.3% vs. n = 105, 42.7%), and this difference was also found to be statistically significant (p = 0.038). The number of vaginal deliveries was higher in the control group (n = 70, 69.3% vs. n = 31, 30.7%), while the number of cesarean deliveries was higher in the study group (n = 210, 53.8% vs. n = 180, 46.2%). Among patients who delivered vaginally, the difference between groups was statistically significant (p = 0.01). In the study group, hypercoiled umbilical cords were observed in 41 patients (17%), hypocoiled cords in 30 patients (12.5%), and normocoiled cords in 170 patients (70.5%) (Figure 1). In the control group, hypercoiling was observed in 16 patients (6.5%), hypocoiling in 17 patients (7%), and normocoiling in 217 patients (86.5%) (Figure 2). Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission was required for 10 newborns (58.8%) in the study group and 7 newborns (41.2%) in the control group; however, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.414) (Table 2).

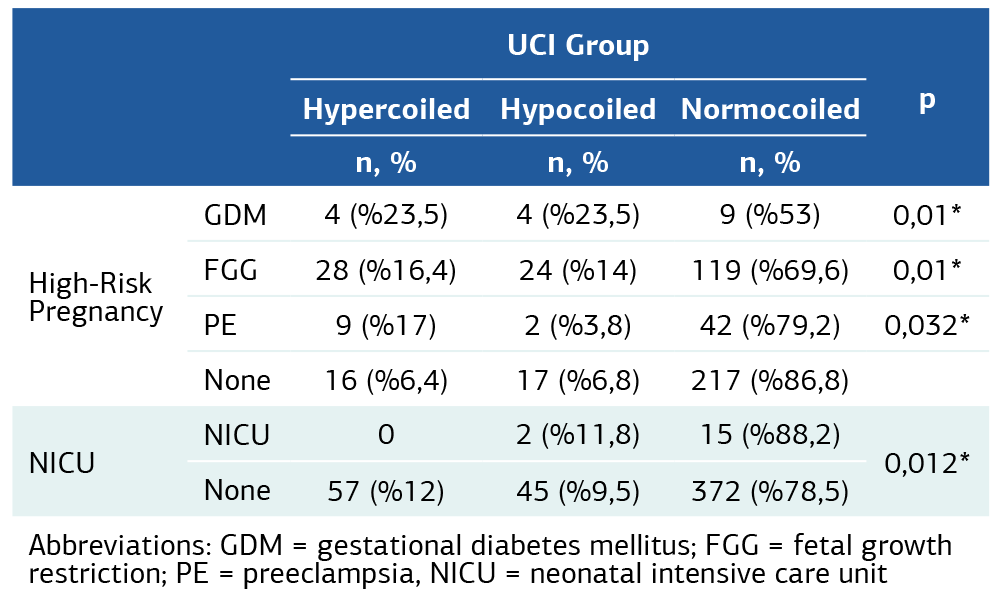

In the GDM group, hypercoiled umbilical cords were observed in 4 patients (23.5%), hypocoiled cords in 4 patients (23.5%), and normocoiled cords in 9 patients (53%). The frequency of normocoiling was statistically higher compared to the other types (p = 0.01). Among high-risk pregnancies, the most frequently observed pathology was FGR. In this group, hypercoiling was observed in 28 patients (16.4%), hypocoiling in 24 patients (14%), and normocoiling in 119 patients (69.6%). The normocoiled group was significantly more frequent than the hypercoiled and hypocoiled groups (p = 0.01). In the preeclampsia group, hypercoiling was observed in 9 patients (17%), hypocoiling in 2 patients (3.8%), and normocoiling in 42 patients (79.2%). Normocoiling was significantly more common than the other two coiling patterns (p = 0.032). NICU admission was not required for any fetus with hypercoiled cords. Among fetuses with hypocoiled cords, 2 (11.8%) required NICU admission, while in the normocoiled group, 15 fetuses (88.2%) required NICU admission. The need for NICU admission was significantly higher in the normocoiled group compared to the others (p = 0.012) (Table 3).

Discussion

The umbilical cord plays a fundamental role in fetal nourishment, and its spiral structure is essential for maintaining this function. Several theories have been proposed regarding the formation of the spiral pattern of the umbilical cord, but no definitive consensus has been reached. The most widely accepted theory suggests a genetic predisposition related to fetal movements and vascular growth patterns.13,14 In a study by Nikkels PGJ et al., four distinct layers were identified in the wall of the umbilical artery: an inner circular layer, an inner longitudinal layer, a large helical muscle layer, and a small helical muscle layer.13 It is believed that the muscle layers in the arterial wall contribute to the spontaneous development of the coiled structure. The spiral configuration of the umbilical cord enhances its strength and flexibility against external forces, playing a crucial role in maintaining uninterrupted blood flow.14 It also contributes to the pressurized transport of blood to the placenta and facilitates diffusion within placental circulation.15

In most previous studies on the umbilical coiling index (UCI), researchers defined hypocoiling, normocoiling, and hypercoiling based on the distribution of their study populations, rather than using a standardized reference. Therefore, a universally accepted reference range for UCI has not yet been established. In our study, the UCI threshold for the lowest 10% of measurements was calculated as 0.14, and for the highest 90% as 0.32. The mean UCI value across the entire study population was 0.23. Based on this, UCI was categorized as ≤ 0.14 = hypocoiling, 0.15–0.31 = normocoiling, and ≥ 0.32 = hypercoiling. In reference studies, the lower 10th percentile was often below our cutoff, while the upper 90th percentile exceeded 0.3. In our study, the upper limit was similar, but the lower limit was notably higher.16

We found that UCI decreased with increasing gestational age. Although Rana et al. reported that the number of coils observed in the first trimester is roughly equivalent to that observed at term, some studies have noted discrepancies between prenatal UCI measurements taken in early pregnancy and postnatal UCI values, with a tendency toward more hypercoiled patterns in prenatal assessments.2,17,18 These findings support the observation in our study that coil number may increase with gestational age. When UCI groups were examined in our study, In the high-risk pregnancy group, hypercoiled cords were observed in 41 patients (17%) and hypocoiled cords in 30 patients (12.5%). Both hypercoiled and hypocoiled cords were observed more frequently in the high-risk pregnancy group compared with the normocoiled group, and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.01). Several studies have shown that deviations from normal umbilical cord coiling—either hypercoiling or hypocoiling—are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, supporting the findings of our study.14 The first study on the impact of UCI on pregnancy outcomes was conducted by Strong et al., who reported that pregnancies outside the normocoiled group had significantly higher rates of intrauterine fetal death, preterm delivery, operative delivery due to fetal distress, and meconium-stained amniotic fluid.7

In our study, GDM was observed in both the hypercoiled (4 patients, 23.5%) and hypocoiled (4 patients, 23.5%) groups, while 9 patients (53%) were in the normocoiled group. One study reported a higher rate of GDM in the hypercoiled group, while another study by Ezimokhai et al. observed higher rates of GDM in both hypo- and hypercoiled groups.4,19 Similarly, FGR was observed in 28 patients (16.4%) in the hypercoiled group, 24 (14%) in the hypocoiled group, and 119 (69.6%) in the normocoiled group, making FGR the most common pathology across subgroups. Studies by Predanic et al. and De Laat et al. also found increased FGR in both hypo- and hypercoiled groups.20 A meta-analysis similarly found that neonates in both the hypocoiled and hypercoiled groups had lower birth weights.21

In the preeclampsia group, 9 patients (17%) had hypercoiled cords, 2 patients (3.8%) had hypocoiled cords, and 42 patients (79.2%) had normocoiled cords. While GDM and FGR cases showed relatively equal distribution between hypo- and hypercoiled groups, preeclampsia was more frequently associated with hypercoiling. However, in contrast to our findings, some publications have reported a greater prevalence of preeclampsia in hypocoiled pregnancies.19,22 Another study found that both hypocoiled and hypercoiled groups were more likely to experience pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders.23 There are also studies showing no significant association between UCI and hypertensive disorders, and a large meta-analysis concluded that there is no meaningful relationship between UCI and the development of preeclampsia.20,21

Some studies have investigated the pathological effects of UCI. De Laat et al. suggested that in the hypercoiled group, increased arterial pressure may impair flow dynamics and reduce pressure in terminal capillaries.15 Similarly, Ernst et al. reported that the hypercoiled group may be at higher risk for vascular obstruction and adverse outcomes during delivery.24 In the hypocoiled group, there may be reduced persistence of end-systolic pressure in the arterial wall of the umbilical cord. To evaluate this, the relationship between UA Doppler patterns and UCI needs to be examined. However, there is currently a lack of literature on this topic, and further studies are needed to investigate the correlation between Doppler velocimetry and UCI.

Limitations

Umbilical artery Doppler ultrasonography was performed on all patients within 1 week of delivery; this period could have been shorter. Pregnancies over 24 weeks were included in the study; adjusting this limit to 32 or 34 weeks would have provided more sensitive results.

Conclusion

In our study, we compared UA Doppler S/D ratios with UCI, both overall and separately for high-risk versus normal pregnancies. As a result, we found no significant difference between the high-risk and normal pregnancy groups. We believe that more extensive studies with larger sample sizes are needed to demonstrate a possible relationship between ultrasonographic Doppler parameters and UCI.

Figures

Figure 1. Number and percentage of hypercoils, normocoils, and hypocoils in the study group

Figure 2. Number and percentage of hypercoils, normocoils and hypocoils in the control group

Tables

Table 1. Age, fetal parameters, S/D value, and umbilical cord properties

Abbreviations: UCI = umbilical cord coiling inde;, UA S/D = umbilical artery systole/diastole ratio

Table 2. Gender of fetuses, delivery types, UCI variables, and NICU requirement characteristics among groups

Abbreviations :UCI: = umbilical cord coiling index; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit; VB = Vaginal birth; C/S = ceserean section

Table 3. Comparison of subgroups of the high-risk pregnancy group, comparison of the need for NICU according to UCI subgroups

Abbreviations: GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; FGG = fetal growth restriction; PE = preeclampsia, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit

References

-

Strong TH Jr, Jarles DL, Vega JS, Feldman DB. The umbilical coiling index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(1 Pt 1):29-32.

-

Nguyen Tran TN, Nguyen HT, Cao NT, et al. Umbilical cord coiling index in predicting neonatal outcomes: a single-center cross-sectional study from Vietnam. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025;38(1):2517763. doi:10.1080/147 67058.2025.2517763

-

de Laat MW, van der Meij JJ, Visser GH, Franx A, Nikkels PG. Hypercoiling of the umbilical cord and placental maturation defect: associated pathology? Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10(4):293-9. doi:10.2350/06-01-0015.1

-

Ernst LM, Minturn L, Huang MH, Curry E, Su EJ. Gross patterns of umbilical cord coiling: correlations with placental histology and stillbirth. Placenta. 2013;34(7):583-8. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.04.002

-

Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population- based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19(3):127-32. doi:10.1055/s-2002-25311

-

Chitra T, Sushanth YS, Raghavan S. Umbilical coiling index as a marker of perinatal outcome: an analytical study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:213689. doi:10.1155/2012/213689

-

Predanic M, Perni SC, Chasen ST, Baergen RN, Chervenak FA. Assessment of umbilical cord coiling during the routine fetal sonographic anatomic survey in the second trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24(2):185-91. doi:10.7863/ jum.2005.24.2.185

-

Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Dowswell T. Fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in high-risk pregnancies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD007529. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007529.pub4

-

Baschat AA, Gembruch U. The cerebroplacental Doppler ratio revisited. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(2):124-7. doi:10.1002/uog.20

-

Ghosh GS, Gudmundsson S. Uterine and umbilical artery Doppler are comparable in predicting perinatal outcome of growth-restricted fetuses. BJOG. 2009;116(3):424-30. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02057.x

-

De Laat MW, Franx A, Bots ML, Visser GH, Nikkels PG. Umbilical coiling index in normal and complicated pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1049-55. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000209197.84185.15

-

Elsayed W, Sinha A. Umbilical cord abnormalities and pregnancy outcome. 2023;6(3):183-9.

-

de Laat MW, Nikkels PG, Franx A, Visser GH. The Roach muscle bundle and umbilical cord coiling. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(9):571-4. doi:10.1016/j. earlhumdev.2006.12.003

-

De Laat MW, Franx A, Van Alderen ED, Nikkels PG, Visser GH. The umbilical coiling index, a review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17(2):93-100. doi:10.1080/14767050400028899

-

De Laat MW, Van Der Meij JJ, Visser GH, et al. Hypercoiling of the umbilical cord and placental maturation defect: associated pathology? Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10(4):293-9. doi:10.2350/06-01-0015.1

-

Van Diik CC, Franx A, De Laat MW, Bruinse HW, Visser GH, Nikkels PG. The umbilical coiling index in normal pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11(4):280-3.

-

Sharma B, Bhardwaj N, Gupta S, Gupta PK, Verma A, Malviya K. Association of umbilical coiling index by colour Doppler ultrasonography at 18-22 weeks of gestation and perinatal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62(6):650-4. doi:10.1007/s13224-012-0230-0

-

Ichizuka K, Hasegawa J, Matsuoka R, et al. Ultrasonic studies on amniotic fluid, umbilical cord and placenta. Donald Sch J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;5(1):65-72. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10009-1179

-

Chitra T, Sushanth YS, Raghavan S. Umbilical coiling index as a marker of perinatal outcome: an analytical study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:213689. doi:10.1155/2012/213689

-

Dogne N, Wadhwani R, Ahirwar N, Chellaiyan VG, Britto J, Singh A. Association of umbilical cord coiling and medical disorders of pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Maedica (Bucur). 2023;18(2):227-31. doi:10.26574/ maedica.2023.18.2.227

-

Pergialiotis V, Kotrogianni P, Koutaki D, Christopoulos-Timogiannakis E, Papantoniou N, Daskalakis G. Umbilical cord coiling index for the prediction of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis and sequential analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(23):4022-9. doi:10.1080/14767058.2019.159418 7

-

Chaurasia BD, Agarwal BM. Helical structure of the human umbilical cord. Acta Anat (Basel). 1979;103(2):226-30. doi:10.1159/000145013

-

Hoseinalipour Z, Javadian M, Nasiri-Amiri F, Nikbakht HA, Pahlavan Z. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and the abnormal umbilical cord coiling index. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2024;17(5):681-8. doi:10.3233/NPM-230106

-

Ernst LM, Minturn L, Huang MH, et al. Gross patterns of umbilical cord coiling: correlations with placental histology and stillbirth. Placenta. 2013;34(7):583–8. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.04.002

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Van Yuzuncu Yil University (Date: 2022-06-13, No: 07)

Informed Consent

In our study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.Ç., O.K.

Methodology: O.K.

Formal Analysis: O.K.

Investigation: O.K., A.Ç.

Data Curation: A.Ç.

Writing – Original Draft Preparation: A.Ç.

Writing – Review & Editing: O.K.

Supervision: O.K.

Abbreviations

BMI: Body Mass Index

C/S: Cesarean Section

FGR: Fetal Growth Restriction

GDM: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

SD: Standard Deviation

S/D: Systole/Diastole Ratio

UA: Umbilical Artery

UCI: Umbilical Cord Coiling Index

VB: Vaginal Birth

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Ali Çakır, Onur Karaaslan. Relationship between umbilical cord coiling index and umbilical artery doppler S/D ratio in high-risk pregnancies. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(Suppl 1):S59-64

Publication History

- Received:

- October 25, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 2, 2025

- Published Online:

- December 13, 2025

- Printed:

- February 20, 2026