Diagnostic value of the STONE score and point-of-care renal ultrasonography in patients presenting with suspected renal colic

STONE score and renal USG in suspected renal colic

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the STONE score and hydronephrosis detected by point-of-care renal ultrasonography (USG) in predicting urinary tract stones and/or hydronephrosis confirmed by non-contrast abdominal computed tomography (CT) in patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with suspected renal colic.

Methods This prospective observational study included patients aged 18 years and older who presented to the ED with unilateral flank pain and were scheduled for non-contrast abdominal CT. Before CT imaging, all patients underwent point-of-care renal USG performed by emergency medicine specialists to assess for hydronephrosis. Demographic and clinical data were recorded, and STONE scores were calculated. CT was subsequently performed to confirm the presence of urinary tract stones and/or hydronephrosis.

Results A total of 191 patients were enrolled. CT confirmed stones and/or hydronephrosis in 70.7% of cases. The area under the curve (AUC) for the STONE score was 0.716, with a sensitivity of 58.3% and specificity of 76.1%. Hydronephrosis detected by USG showed a markedly higher diagnostic performance, with an AUC of 0.915, sensitivity of 95.2%, and specificity of 98.5%.

Conclusion Although the STONE score showed good specificity, particularly in high-score patients, its sensitivity remained limited. Hydronephrosis detected by point-of-care renal USG performed by experienced emergency physicians demonstrated both high sensitivity and specificity, indicating that USG may be a more reliable tool than the STONE score for predicting urinary tract stones in ED patients.

Keywords

Introduction

Renal colic is a common cause of emergency department (ED) visits, with a lifetime prevalence ranging between 5% and 15% worldwide. Although non-contrast computed tomography (CT) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing patients with suspected urinary tract stones, this imaging modality has some disadvantages, including exposing patients to ionizing radiation and prolonging ED length of stay 1,2,3,4. Preventing unnecessary CT imaging is particularly important in young patients with uncomplicated renal colic. The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) recommends reducing routine abdominal and pelvic CT imaging in patients with a known history of urolithiasis, aged < 50 years, and presenting with clinically uncomplicated renal colic. This recommendation is based on the low likelihood of CT providing additional diagnostic benefit in this patient population and the need to avoid unnecessary radiation exposure 3. Therefore, there is an increasing need in ED practice for alternative diagnostic methods that are rapid, radiation-free, and have high diagnostic accuracy.

In recent years, clinical decision support tools such as the STONE score and point-of-care renal USG have been increasingly utilized in the ED to reduce the need for CT imaging 4,5,6,7. The STONE score is a clinical prediction tool based on five parameters: sex, duration of pain prior to presentation, race, presence of nausea or vomiting, and hematuria on urine dipstick analysis. Points are assigned to each component as follows: male sex (2 points); pain duration < 6 hours (3 points), 6–24 hours (1 point), and > 24 hours (0 points); non-Black race (3 points); nausea (1 point) or vomiting (2 points); and presence of hematuria (3 points). The total score ranges from 0 to 13, with patients categorized into low (0–5), moderate (6–9), and high (10–13) probability groups for urinary tract stones. This risk stratification may assist clinicians in estimating the likelihood of urolithiasis and in guiding decision-making regarding the need for computed tomography imaging [5–7]. Point-of-care renal USG does not directly visualize the stone itself but detects hydronephrosis, a secondary finding resulting from obstruction caused by the stone. The presence of hydronephrosis on USG provides important clues regarding the presence of stones and the potential need for urologic intervention. Moreover, this method can be performed rapidly and non-invasively at the bedside by emergency physicians 8,9,10,11,12.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the STONE score and bedside renal USG in predicting the presence of urinary tract stones and/or hydronephrosis detected by non-contrast abdominal CT in patients presenting to the ED with a preliminary diagnosis of renal colic.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This prospective observational study was conducted in the emergency department of Ankara Atatürk Sanatoryum Training and Research Hospital, a 780-bed tertiary care center located in a large provincial area with approximately 385,000 annual emergency department visits. The design and reporting of the study were performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines 13.

Study Population

Patients who presented to the ED between April 1, 2024, and March 31, 2025, with unilateral flank pain and a preliminary diagnosis of renal colic, who were 18 years of age or older, for whom a non-contrast abdominal CT with stone protocol was planned by the emergency physician, and who provided informed consent to participate in the study were included. Patients with generalized abdominal tenderness on physical examination, suspected acute abdomen, additional complaints other than flank pain, a history of urinary tract stones diagnosed in any healthcare facility within the last 3 months, patients who did not undergo CT imaging, and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded. Demographic data, history of urinary stones, duration and side of pain, presence of nausea or vomiting, hematuria in urine analysis, and components of the STONE score were recorded using a standardized data collection form. In addition, ultrasonographic findings (presence and grade of hydronephrosis) and CT results (presence, size, and location of ureteral stones, as well as the presence of hydronephrosis) were documented for all patients.

Before CT imaging, all patients included in the study underwent focused bedside renal USG performed by emergency medicine specialists who had completed residency training and had at least 5 years of experience in emergency care. Hydronephrosis on the symptomatic side was evaluated during these USG examinations. Hydronephrosis was graded using a four-level ultrasonographic classification: Grade 1—mild pelvic dilatation without calyceal involvement; Grade 2—dilatation of the renal pelvis with a few calyces becoming visible; Grade 3—diffuse calyceal dilatation with preserved cortical thickness; and Grade 4—severe calyceal dilatation accompanied by cortical thinning. All USG assessments were performed by physicians who routinely use USG in their ED practice and have significant experience in this field.

Following USG evaluation, the clinical characteristics of each patient were assessed using the STONE score, and data were recorded on a standardized form. After ultrasonographic and clinical evaluations, a non-contrast abdominal CT scan with a stone protocol was performed on all patients, and the presence of urinary tract stones and/or hydronephrosis was recorded according to the radiology reports. Importantly, all CT examinations were interpreted by radiologists who were unaware of the patients’ USG findings and STONE scores, and who were working independently from the study team. Thus, blinding was ensured during CT reporting to minimize potential observer bias. Additionally, the final outcomes of the patients in the ED (discharge or hospitalization) and whether they underwent any urological intervention related to stone disease within 30 days were recorded and followed on.

Data Analysis

All data obtained during the study were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) software package. The conformity of continuous and numerical variables to a normal distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Shapiro-Wilk test, histograms, and Q-Q plot graphics. Continuous and numerical variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (minimum– maximum), depending on the distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage (%). Categorical variables between two groups were compared using the chi-square test. For continuous variables, the independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used according to the distribution of the data. The diagnostic accuracy of the STONE score (≥ 10) and the presence of hydronephrosis on renal USG for predicting the presence of stones and/or hydronephrosis detected by CT was evaluated using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were calculated based on the ROC analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Based on the study by Lee et al., titled “Renal point-of-care ultrasound performed by ED staff with limited training and 30- day outcomes in patients with renal colic,” a 30-day urological intervention rate difference of 8.7% was observed between hydronephrotic (11.2%) and non-hydronephrotic (2.5%) groups 4. Considering this 8% effect size, with a significance level of α = 0.05 and a power of 0.8, the sample size for the present study was calculated to be 90 patients for each group. To account for possible protocol deviations, it was planned to include 95 patients in each group, resulting in a total sample size of 190 patients.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Atatürk Sanatoryum Training and Research Hospital (Date: 2024-02- 28, No: 2024-BÇEK/33).

Results

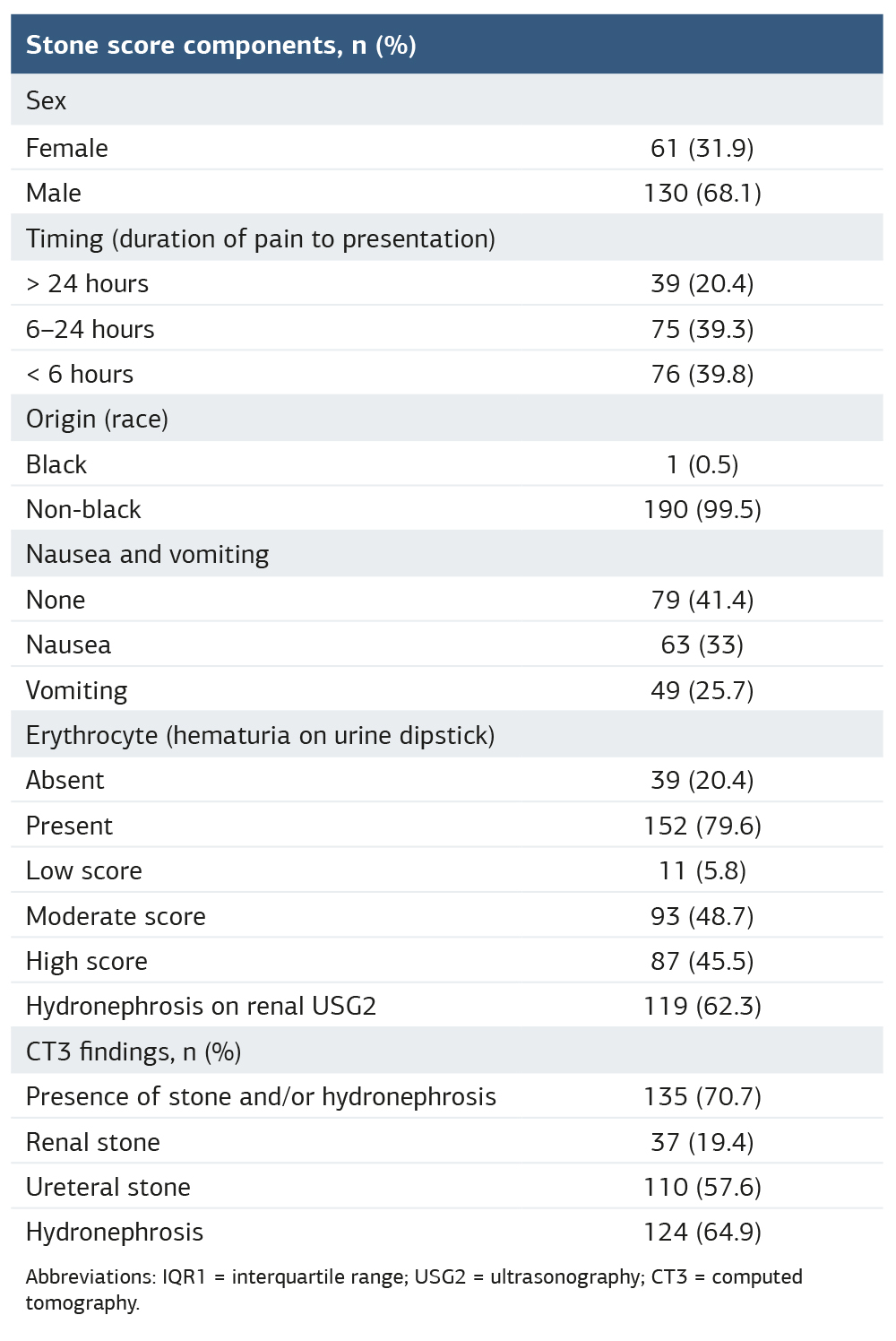

A total of 191 patients were included in the study. The median age of the patients was 49 years (IQR 25-75: 34-62), and 68.1% of them were male. The median duration of pain before presentation was 8 hours (IQR 25-75: 4-16), and 39.3% of the patients had a history of urolithiasis. Hematuria was detected in 79.6% of patients on urinalysis. According to the STONE score, 5.8% of the patients were classified as low-risk, 48.7% as moderate-risk, and 45.5% as high-risk. Hydronephrosis was detected in 62.3% of the patients by renal USG. On non- contrast abdominal CT, stone and/or hydronephrosis was detected in 70.7% of the patients. Additionally, 9.9% of the patients were hospitalized, and 18.3% underwent a urological intervention within 30 days, including nephrostomy in 5.8% and ureterorenoscopy in 13.1% of the cases. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. When patients were compared according to the presence of stone and/or hydronephrosis on CT, the duration of pain was significantly shorter in the CT-positive group (median: 7 hours, IQR 25-75: 4-12) (p = 0.001). The rate of patients with a history of urolithiasis was significantly higher in the CT-positive group (48.1%) compared to the CT-negative group (17.9%) (p < 0.001). In terms of gender distribution, the proportion of male patients was higher in the CT-positive group (75.6%) than in the CT-negative group (50%) (p = 0.001). When classified according to the duration of pain, pain lasting less than 6 hours was more common in the CT-positive group, while pain lasting more than 24 hours was more frequent in the CT-negative group (p = 0.049). The presence of hematuria was observed in 88.1% of CT-positive patients, whereas it was detected in 58.9% of CT- negative patients (p < 0.001). According to the STONE score, a high score was significantly more frequent in CT-positive patients (53.3% vs. 26.8%; p < 0.001). In addition, 86.7% of patients with hydronephrosis detected by renal USG were in the CT-positive group, while this rate was only 3.6% in the CT- negative group (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S1).

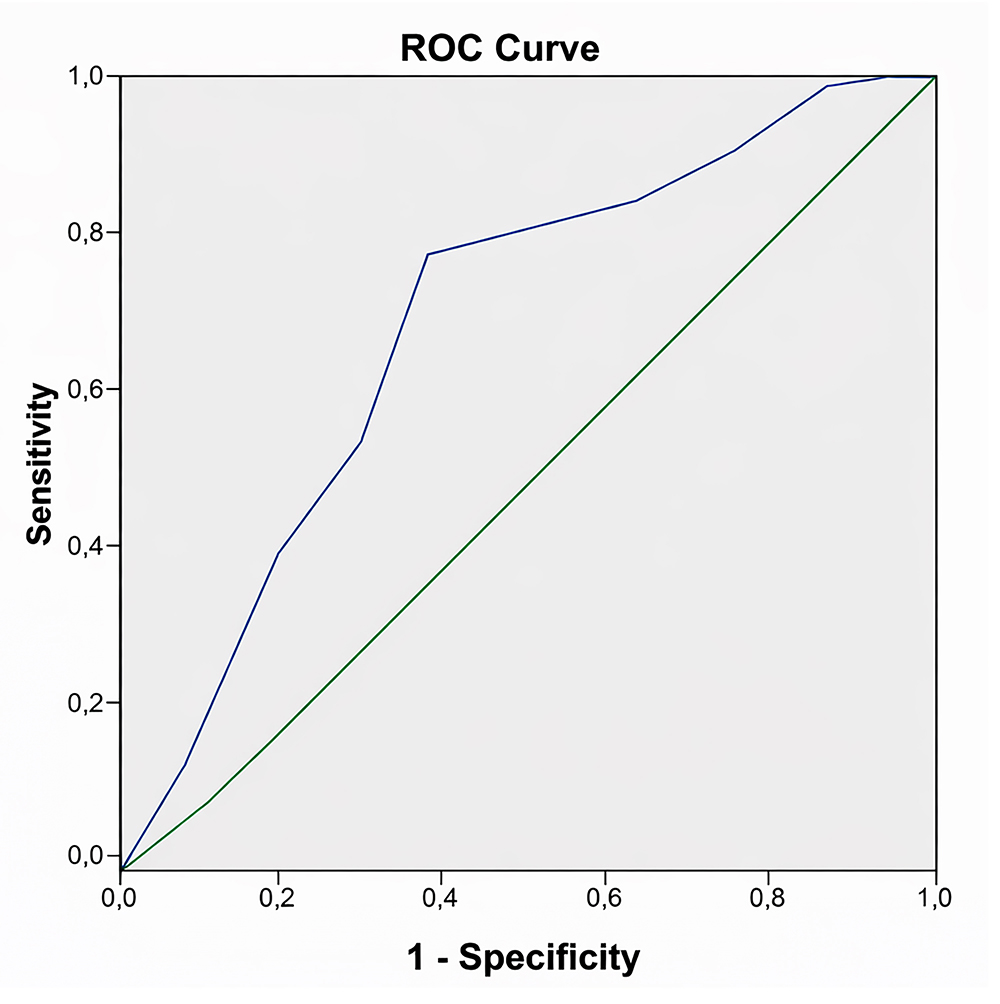

The diagnostic accuracy of the STONE score in predicting the presence of stone and/or hydronephrosis in the urinary system was evaluated, and the AUC obtained from the ROC analysis was found to be 0.716 (95% CI, 0.634–0.798, p < 0.001) (Figure1).

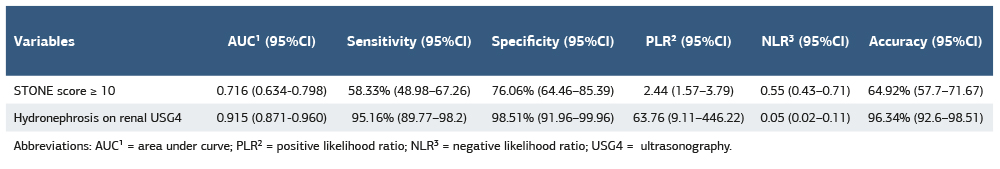

The comparison of the diagnostic performances of the STONE score (≥ 10) and the presence of hydronephrosis on renal USG in predicting urinary tract stones is presented in Table 2. In the ROC analysis of the STONE score, AUC was found to be 0.716 (95% CI, 0.634–0.798, p < 0.001), with a sensitivity of 58.33% and a specificity of 76.06%. In contrast, the AUC value for the presence of hydronephrosis detected by renal USG was found to be remarkably higher at 0.915 (95% CI, 0.871–0.960, p < 0.001), with a sensitivity of 95.16% and a specificity of 98.51%.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the STONE score and bedside renal ultrasonography (USG) in predicting the presence of urinary stones and/ or hydronephrosis identified by non-contrast abdominal CT in patients presenting to the ED with unilateral flank pain. Understanding the reliability of these tools is essential for optimizing diagnostic strategies and reducing unnecessary radiation exposure in emergency settings. The findings of the study demonstrated that both methods have diagnostic value; however, renal USG was observed to have higher sensitivity and specificity. These results suggest that the use of bedside renal USG, particularly in appropriate clinical scenarios, may contribute to reducing unnecessary CT imaging in the ED.

In recent years, with the increasing use of bedside USG in ED practice, numerous studies have been published investigating its diagnostic value. USG has become an important tool in clinical decision-making processes, particularly in common conditions such as renal colic, due to its safety, rapid applicability, and radiation-free imaging capability. USG is considered a valuable method in the diagnosis of symptomatic urinary stones, as it can detect both the stones directly and the secondary findings caused by the stones, such as hydronephrosis. However, studies conducted by emergency physicians have reported sensitivity values ranging from 72% to 97% and specificity values ranging from 69% to 83%, indicating that the diagnostic accuracy of USG may vary 4,8,9,10,11,12,14. This variability is thought to arise mainly from factors such as the experience level of the practitioners, the techniques used, and patient characteristics. Therefore, it is recommended that USG be used not as a standalone tool but in combination with clinical scoring systems in the decision- making process, in order to enhance diagnostic accuracy and achieve more reliable results.

In our study, the AUC value of the STONE score was found to be 0.716, with a sensitivity of 58.3% and a specificity of 76.1%. In a previous study, the specificity of the STONE score in patients with a high score (≥ 10) was reported to be as high as 87%, although it was emphasized that this high specificity alone was not sufficient to eliminate the need for CT imaging 7. In another study, it was noted that the specificity of the STONE score was already high in patients with a high score (≥ 10), and adding renal USG in this group did not provide a significant additional contribution to diagnostic accuracy. However, in the same study, it was reported that the addition of USG to the STONE score increased specificity in the low- and intermediate-risk groups 14. On the other hand, a modified STONE score (MSS), in which certain components of the original score (such as race) were excluded and replaced with more clinically applicable parameters such as a history of stones and pain characteristics, was shown to further improve diagnostic accuracy. In this study, the presence of stones was detected in 96% of patients with a high MSS score 15. Additionally, in another study conducted in an Asian population, the specificity of the STONE score was found to be lower (approximately 69%), and it was emphasized that the score alone might not be sufficient for imaging decisions in this population 16. These findings suggest that the performance of the STONE score may vary across different populations and clinical scenarios. Our study also contributes to the literature by evaluating the validity of this scoring system in a local patient population. Although the MSS was not directly applied in our study, some of our findings—particularly the significant association between a history of urolithiasis and CT positivity, as well as the relevance of pain duration— align with variables emphasized in the MSS. The MSS was developed by removing less clinically relevant components of the original STONE score (such as race) and incorporating more practical parameters, and previous studies have reported that this modification may improve diagnostic accuracy in certain populations. Given that the predictors highlighted in the MSS also demonstrated significance in our cohort, it is possible that the MSS could have offered comparable or even enhanced diagnostic performance in our study population.

Pain duration is one of the key components of the STONE score, and previous studies have consistently reported that shorter pain duration is associated with a higher likelihood of ureteral stones 5,6,14,15,16. Similar to the existing literature, our study also demonstrated that CT-positive patients had significantly shorter pain duration. This finding is consistent with the pathophysiological expectation that acute ureteral obstruction causes sudden-onset, severe flank pain, prompting patients to seek medical attention earlier. Therefore, the relationship between shorter pain duration and stone presence in our cohort supports the predictive value of this parameter within the STONE score.

In our study, bedside renal USG demonstrated a notably high diagnostic accuracy for detecting hydronephrosis. The obtained AUC value was 0.915, with a sensitivity of 95.2% and a specificity of 98.5%. In a previous study conducted in patients with CT-confirmed urolithiasis, the sensitivity of bedside USG in detecting hydronephrosis was reported as 78.4%, while the overall sensitivity for positive findings (hydronephrosis or direct visualization of the stone) was found to be 82.4%. This study also showed that as the stone size increased, the sensitivity improved, reaching up to 90% for stones larger than 6 mm 12. Similarly, another study reported an overall sensitivity of 72.6% and a specificity of 76.9%, but the sensitivity increased to 92.7% when USG was performed by physicians with dedicated ultrasound training 8. These findings highlight that USG is operator-dependent, and the experience level of the practitioner plays a critical role in diagnostic accuracy. In another study, the overall sensitivity and specificity of bedside focused renal USG were reported as 75.8% and 55.2%, respectively; however, these values increased with the severity of hydronephrosis, with specificity rising to 85.7% for moderate hydronephrosis 10. Considering the variability in the literature, the high sensitivity and specificity achieved in our study may be attributed to the fact that renal USG was performed by experienced emergency medicine specialists using a standardized protocol. These findings support that the diagnostic accuracy of renal USG can be significantly improved with appropriate practitioner training and standardized evaluation protocols.

Although USG offers significant advantages such as the absence of radiation exposure, rapid applicability, and bedside availability, it may not provide sufficient information as a standalone diagnostic tool in every clinical scenario. However, when performed in appropriate clinical settings and by experienced emergency physicians, it may contribute to reducing unnecessary CT imaging. Therefore, USG findings should be interpreted in conjunction with clinical evaluation and scoring systems, and when necessary, decisions regarding advanced imaging should be based on the physician’s clinical judgment and patient-specific risk assessment for the most appropriate approach.

Limitations

This study was conducted in a single center, and the sample size was relatively limited. Another important limitation is the operator-dependent nature of bedside ultrasonography. Since all USG examinations were performed by experienced emergency physicians, the diagnostic accuracy observed in our study may be higher than that of clinicians with varying levels of training and experience. Therefore, the generalizability of the results to different clinical settings may be limited. Lastly, detailed radiological data such as stone size and location were not systematically analyzed in this study; therefore, the impact of these variables on the diagnostic performance of the tests could not be evaluated.

Conclusion

While the STONE score stands out as a clinical tool with high specificity, particularly in patients with high scores, its sensitivity remains limited. In contrast, hydronephrosis detected by bedside renal USG performed by experienced emergency physicians demonstrated both high sensitivity and specificity in predicting the presence of urinary stones. Our findings suggest that bedside renal USG may serve as a reliable and rapid first- line imaging modality in patients with low-to-intermediate STONE scores and may help reduce unnecessary CT imaging. However, decisions regarding further imaging should be supported by patient-specific clinical evaluation.

Figures

Figure 1. ROC curve of the STONE score for predicting the presence of urinary tract stones

Tables

Table 1. Demographics and some laboratory findings of the patients

Abbreviations: IQR1 = interquartile range; USG2 = ultrasonography; CT3 = computed tomography.

Table 2. Diagnostic performance metrics of STONE Score (≥10) and hydronephrosis on renal ultrasound for the detection of urinary tract stones

Abbreviations: AUC¹ = area under curve; PLR² = positive likelihood ratio; NLR³ = negative likelihood ratio; USG4 = ultrasonography.

References

-

Patti L, Leslie SW. Acute renal colic [Internet]. StatPearls. 2024 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431091/.

-

Tandoğan M, Emektar E, Dağar S, et al. The effect of severe pain on transmyocardial repolarization parameters in renal colic patients. Eurasian J Emerg Med. 2022;21(3):188-92. doi:10.4274/eajem.galenos.2020.42275.

-

Moore CL, Carpenter CR, Heilbrun ME, et al. Imaging in suspected renal colic: systematic review of the literature and multispecialty consensus. J Urol. 2019;202:475-83. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000342.

-

Lee WF, Goh SJ, Lee B, Juan SJ, Asinas-Tan M, Lim BL. Renal point-of-care ultrasound performed by ED staff with limited training and 30-day outcomes in patients with renal colic. CJEM. 2024;26(3):198-203. doi:10.1007/s43678-023-00645-5.

-

Kim B, Kim K, Kim J, et al. External validation of the STONE score and derivation of the modified STONE score. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1567-72. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.05.061.

-

Moore CL, Bomann S, Daniels B, et al. Derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for uncomplicated ureteral stone--the STONE score: retrospective and prospective observational cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2191. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2191.

-

Wang RC, Rodriguez RM, Moghadassi M, et al. External validation of the STONE score, a clinical prediction rule for ureteral stone: an observational multi-institutional study. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(4):423-32.e2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.08.019.

-

Herbst MK, Rosenberg G, Daniels B, et al. Effect of provider experience on clinician-performed ultrasonography for hydronephrosis in patients with suspected renal colic. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(3):269-76. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.012.

-

Szataniak I, Packi K. Melatonin as the missing link between sleep deprivation and immune dysregulation: a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(14):6731. doi:10.3390/ijms26146731.

-

Al-Balushi A, Al-Shibli A, Al-Reesi A, et al. The accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound performed by emergency physicians in detecting hydronephrosis in patients with renal colic. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2022;22(3):351-6. doi:10.18295/squmj.9.2021.130.

-

Sibley S, Roth N, Scott C, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for the detection of hydronephrosis in emergency department patients with suspected renal colic. Ultrasound J. 2020;12(1):31. doi:10.1186/s13089-020-00178-3.

-

Riddell J, Case A, Wopat R, et al. Sensitivity of emergency bedside ultrasound to detect hydronephrosis in patients with computed tomography-proven stones. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(1):96-100. doi:10.5811/westjem.2013.9.15874.

-

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-9. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2007.11.008.

-

Daniels B, Gross CP, Molinaro A, et al. STONE PLUS: evaluation of emergency department patients with suspected renal colic, using a clinical prediction tool combined with point-of-care limited ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(4):439-48. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.020.

-

Bahadirli S, Sen AB, Bulut M, Kaya S. Evaluation of the patients with flank pain in the emergency department by modified STONE score. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;47:158-63. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.073.

-

Ang JS, Wong SYV, Ooi CK. Use of STONE score to predict urolithiasis in an Asian emergency department. J Acute Med. 2022;1;12(2):53-9. doi:10.6705/j. jacme.202206_12(2).0002.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Atatürk Sanatoryum Training and Research Hospital (Date: 2024-02-28, No: 2024-BÇEK/33)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Handan Özen Olcay, Emine Emektar, Şeref Kerem Çorbacıoğlu, Hilal Esra Yaygın, Selma Uysal Ramadan, Yunsur Çevik. Diagnostic value of the STONE score and point-of-care renal ultrasonography in patients presenting with suspected renal colic. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(2):152-157

Publication History

- Received:

- November 4, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 15, 2025

- Published Online:

- January 23, 2026

- Printed:

- February 1, 2026