The relationship of athletic performance with certain physiological parameters in adolescent middle distance runners

Physiological Determinants of Performance in Runners

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study aimed to examine the relationship between respiratory function values and selected athletic performance parameters of track and field athletes. The research was conducted with the voluntary participation of 27 male athletes aged 14-18, with an average training age of 3 years.

Methods As part of the study, performance athletes underwent anthropometric measurements and subcutaneous fat tissue measurements, along with the following tests: Cooper test, sit-and-reach test, flamingo balance test, vertical jump test, standing long jump test, leg-back strength test, and handgrip strength test. Additionally, a Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) was administered to the athletes to determine their lung respiratory capacity. The data were processed and analyzed using the SPSS 26 software package, and the results were evaluated at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results The athletes’ respiratory function tests (FVC, FEV₁, FEV₁ / FVC) were largely within normal limits, while PEF was observed to be slightly below normal. When examining the correlations between athletic performance and respiratory functions, aerobic capacity measurements (Cooper Test and MaxVO₂) showed a high degree of positive correlation with FEV₁, while FVC and FEV₁ / FVC showed a moderate degree of positive correlation. Moderate positive correlations were found between strength tests and respiratory parameters, and between flexibility tests and respiratory parameters.

Conclusion The findings indicate that performance and ventilatory capacity can support each other in middle-distance runners, and that training during the preparation period can have positive effects on respiratory functions. In conclusion, the respiratory functions and athletic performance of young middle- distance athletes are at healthy and sufficient levels, and it can be said that performance sports can support lung function.

Keywords

Introduction

It includes essential motor abilities, including cross-country and track running, governed by set regulations and distinct athletic categories 1. Running competitions are divided into short, middle, and long distances. In official competitions, middle- distance races consist of runs between 800 m and 3000 m, and many athletes compete in both the 800 m and 1500 m.

Unlike sprint competitions, middle-distance running doesn’t require maximum speed from start to finish. The fundamental factor determining performance in these branches is the simultaneous use of aerobic and anaerobic energy systems. Specifically in the 800 m and 1500 m distances, both energy systems contribute approximately equally, and this depends on the athlete’s ability to maintain an optimal balance between performance, speed sustainability, and long-term energy requirements 2,3.

It has been specifically mentioned that running improves lung function, which can also help strengthen respiratory muscles. Therefore, regular running is recommended to individuals as it can improve lung function 4.

Success in athletics largely depends on the development of basic motor skills such as strength, endurance, and flexibility. It is extremely important for athletes to have developed characteristics such as speed, technical-tactical skills, and fitness, in addition to endurance, for performance success 5. However, it is well known that the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems are actively involved during muscle exercise, and both of these organ systems undergo adaptive changes in response to regular endurance exercise 6.

In medium-duration endurance training, aerobic and anaerobic efforts are observed simultaneously, with a gradual shift toward aerobic activity 7. For example, it has been reported that the anaerobic system contributes approximately 20% of the energy demands for a 3000 m run, and accounts for 50% of the athlete’s total energy expenditure for a 1500 m run 8. It is emphasized that the main factor determining the basic physical condition of middle-distance runners with such endurance characteristics is their overall level of physical development and relatively high body length, and that the most important determinant of performance in middle-distance running is Maximum Oxygen Consumption (VO2Max) capacity 1. In addition, maximal oxygen uptake (MaxVO2), which is the highest rate at which a child or adolescent can consume oxygen during exercise, is considered the best indicator of aerobic fitness in young people 9. MaxVO2 limits the rate at which oxygen can be supplied during exercise and is therefore an important component of elite performance in many sports (e.g., cycling and track running), but it has been noted that these components do not fully define all aspects of sport-related aerobic fitness 5. Some studies have indicated that a high VO2Max is necessary to perform well in national and international race distances ranging from 3000 meters to the marathon. In addition, it has been reported that the anaerobic system contributes approximately 20% of the energy demands for the 3000 m run and accounts for 50% of the athlete’s total energy expenditure for the 1500 m run 5,10. The Cooper test is used as one of the most reliable and common methods for estimating VO₂Max. In addition to VO₂Max, this test is also an effective tool for assessing cardiovascular endurance and monitoring fitness changes over time 11.

It is known that the beneficial effects of exercise on the respiratory system functions increase overall performance, aerobic power, and working capacity, and reduce shortness of breath. It also increases the MaxVO2 value, which is an indicator of the harmony between the cardiovascular and respiratory systems 12. Therefore, the aerobic capacity of athletes, which is an important factor in athletic success, is considered the best indicator of athletic fitness and, in most cases, cardiorespiratory endurance 13.

During endurance exercise, carbon dioxide production significantly increases, yet the pulmonary system is capable of meeting this increased demand 14. At this level, the respiratory system’s response rate to the increased oxygen demand during exercise is higher in well-trained individuals due to the development of physiological adaptations 15. Therefore, participation in sports is related to respiratory adaptation, and the extent of adaptation depends on the type of activity 6.

Current studies have confirmed that aerobic training applied to middle-distance runners has positive effects on athletic performance by improving basic physiological parameters such as cardiorespiratory capacity 16. In this context, the acute effects of moderate-intensity aerobic endurance training on the athletic performance and respiratory function of middle- distance runners are of interest. The aim of the research conducted in this direction is to determine the relationship between selected endurance and strength-containing athletic performance parameters and respiratory function values in male middle-distance runners who are actively continuing their training.

The hypothesis of this study is that there is a statistically significant relationship between middle-distance runners’ athletic performance and their respiratory function parameters after the preparation period.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study was conducted using a correlational research design, one of the quantitative research methods, to examine the existence, direction, and strength of the relationship between variables.

The population consisted of licensed middle-distance runners registered with clubs affiliated with the Mardin Provincial Directorate of Youth and Sports, while the sample included licensed male middle-distance runners from clubs in the Kızıltepe district of Mardin who competed in official competitions. The required sample size was determined by an a priori power analysis using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 software. Based on a two- tailed test, a medium effect size (|ρ| = 0.50), a significance level of α = 0.05, and statistical power of 1 – β = 0.80, the minimum sample size was calculated as 26; therefore, 27 male athletes were included in the study.

Participants

The research group consisted of 27 volunteer male middle- distance runners aged 14-18, who actively participated in national official competitions and ran distances between 800 and 3000 meters, with an average of 3 years of training experience. The athletes included in the study, aged 14-18, were chosen because they represent the largest population among middle-distance runners in the Mardin region. Before the research, detailed information about the study was provided to each athlete, and they were asked to sign the Informed Consent Form and the Parental Consent Form.

Inclusion criteria were performance middle-distance runners aged 14–18 years who were non-smokers, had no chronic or respiratory diseases, had not experienced an upper respiratory tract infection in the previous 4 weeks, and had no musculoskeletal injuries preventing training for at least 2 weeks.

Exclusion criteria included athletes outside the 14–18 age range, short- or long-distance runners, smokers, those with chronic or respiratory diseases, recent upper respiratory tract infections, or musculoskeletal injuries limiting training for 2 weeks or longer.

Procedure

According to Bompa’s periodization approach, the annual training plan consists of preparation, competition, and transition phases, and each phase targets the physiological adaptations of the athletes. The preparation phase is the period during which the basic physiological infrastructure is established to support the development of general endurance, biomotor abilities, and energy systems, especially for performance. In this phase, the training volume is generally high, the intensity is low, and adaptation is achieved through repeated loading. In this study, athletes were included without considering the 4-week preparation period practices of the clubs, which were based on annual training plan 7. Immediately following the preparation period, athletes were subjected to tests determined within the scope of the research to assess the gains from training and performance levels.

Data Collection Techniques

Within the scope of the research, anthropometric measurements (height, body weight, and BMI (Body Mass Index)) and subcutaneous fat tissue measurements were taken to determine the athletic performance of performance athletes, along with the Cooper test, flexibility test, flamingo balance test, vertical jump test, standing long jump test, leg- back strength, and handgrip strength tests. From physiological parameters, a Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) was administered to athletes to determine lung capacity. In these tests, athletes performed on the athletics track, and after active recovery, the athletes underwent respiratory function tests. Detailed test protocols regarding the implementation of these tests are provided in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and S3.

Statistical Analysis of Data

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and athletic performance and respiratory function variables were standardized using z-scores. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test (n < 30), revealing that some variables (FVC: p = .571; FEV1: p = .220; PEF: p = .164; Cooper test: p = .080; VO2Max: p = .084; vertical jump: p = .731; standing long jump: p = .306; back strength: p = .331; right handgrip strength: p = .516; left handgrip strength: p = .189; flexibility: p = .339] were normally distributed while others [FEV1 / FVC: p = .011-.005; leg strength: p = .028; right foot flamingo balance: p = .000; left foot flamingo balance: p = .000) were not. Accordingly, Pearson correlation analysis was applied to parametric data and Spearman correlation analysis to non-parametric data to examine the relationships between athletic performance and respiratory function parameters. The significance level was determined as p < 0.05.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Non-Invasive Clinical Researches Ethics Committee of Mardin Artuklu University (Date: 2025-09- 18, No: 214463).

Results

The data obtained from athletic performance and respiratory function tests applied to male middle-distance runners in the study are presented in tables in this section.

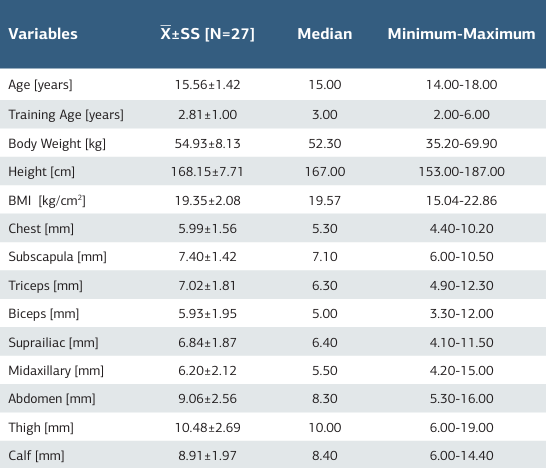

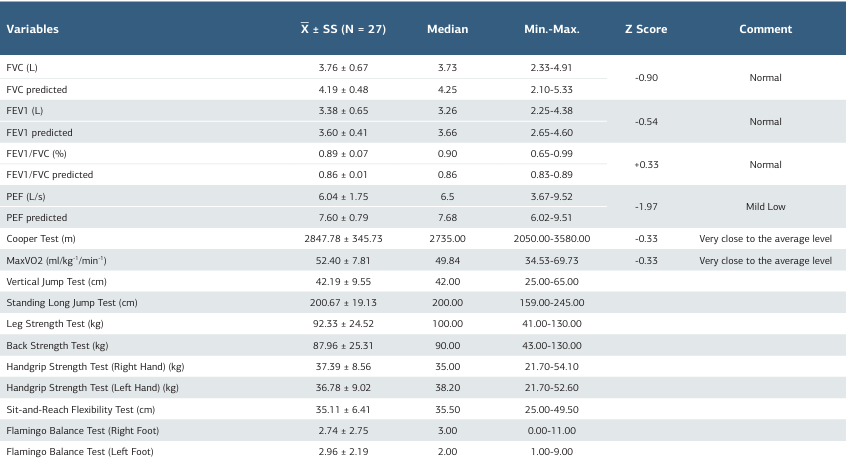

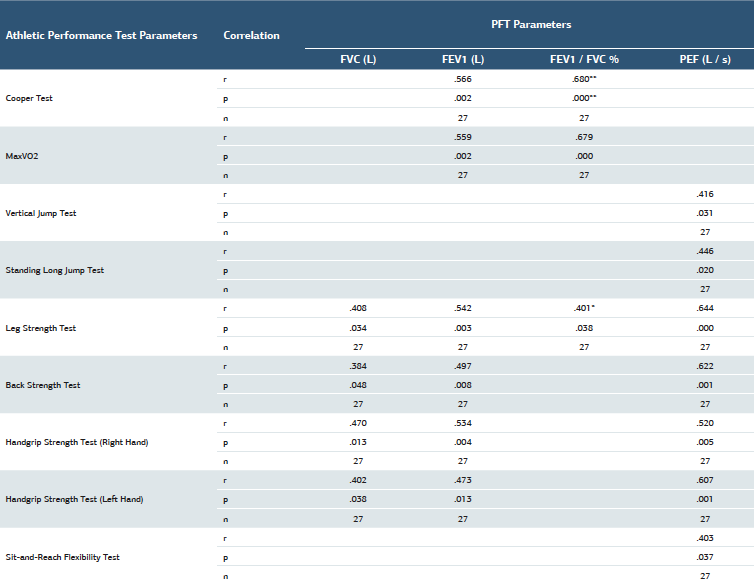

Demographic characteristics of male athletes show that their average age is 15.56 ± 1.42 years, average training age 2.81 ± 1.00 years, with average body weights of 54.93 ± 8.13 kg, average height 168.15 ± 7.71 cm, and the average BMI is 19.35 ± 2.08 kg / cm2. Looking at the skinfold measurements of the tools, the chest averages are 5.99 ± 1.56 mm, subscapula averages 7.40 ± 1.42 mm, triceps averages 7.02 ± 1.81 mm, average biceps measurements 5.93 ± 1.95 mm, suprailiac averages 6.84 ± 1.87 mm, midaxillary averages 6.20 ± 2.12 mm, abdominal averages 9.06 ± 2.56 mm, thigh averages 10.48 ± 2.69 mm and calf averages 8.91 ± 1.97 mm (Table 1). Looking at Table 2, among the respiratory function test parameters, the average FVC value was found to be 3.76 ± 0.67 L, the average FEV1 value was 3.38 ± 0.65 L, the average FEV1 / FVC value was 87.70 ± 9.79%, and the average PEF value was 5.77 ± 1.70 L / s-1. The athletes’ performance test results were as follows: Cooper test average 2847.78 ± 345.73 m, MaxVO2 value average 52.40 ± 7.81 ml / kg-1 / min-1, vertical jump test average 42.19 ± 9.55 cm, standing long jump test average 200.67 ± 19.13 cm, leg strength test average 92.33 ± 24.52 kg, back strength test average 87.96 ± 25.31 kg, right handgrip strength test average 37.39 ± 8.56 kg, left handgrip strength test average 36.78 ± 9.02 kg, sit-and-reach flexibility test average 35.11 ± 6.41 cm, flamingo balance test (right foot) average 2.74 ± 2.75, flamingo balance test (left foot) average 2.96 ± 2.19. Among the PFT parameters, the values of FVC (Z = -0.90), FEV1 (Z = -0.54), and FEV₁ / FVC (Z = +0.3) were confirmed to be within the expected limits based on age and height (Normal range = –1.64 ≤ Z ≤ +1.64). The PEF (Z = -1.97) parameter was found to be below -1.64 and was confirmed to be clinically low. Looking at Table 3, positive and significant relationships were observed between respiratory function parameters and the Cooper Test and MaxVO₂ values. The correlations with FEV1 were high (r = 0.68, p < 0.001), and the correlations with FVC and FEV1 / FVC were moderate (r = 0.56–0.42, p <0 .05). A moderate positive correlation was found between PEF and vertical jump and long jump tests (r = 0.41–0.45, p < 0.05). Moderate to moderately-high positive correlations were found between strength tests (leg strength, back strength, and handgrip) and respiratory functions (r = 0.40–0.64, p < 0.05). A moderate positive correlation was found between flexibility tests and PEF (r = 0.40, p < 0.05). Generally, stronger relationships were observed between aerobic capacity and respiratory functions, while moderate relationships were confirmed between strength and flexibility tests and respiratory parameters.

Discussion

From the respiratory function values of the current study, it was found that FVC, FEV1, and the FEV₁ / FVC ratio, and from the performance measurements, the Cooper test and MaxVO2 scores were within the expected limits based on age and height. However, the Z-score of PEF (-1.97) was below -1.64 and found to be clinically low; this result is thot to be due to measurement technique, maximal expiratory effort, fatigue, or individual differences.

In the study conducted by Kahraman et al. (2023), the respiratory functions of long-distance athletes, soccer players, and sedentary individuals were examined, with an average age of 18.86 ± 1. The respiratory function test values for female long-distance athletes aged 18 were FVC (L) 4.05 ± 0.54 (p = 0.006), FEV1 (L) 3.56 ± 0. It was found to be 42 (p = 0.00). According to the research results, it was determined that the respiratory functions of female long-distance runners were better than those of soccer players and sedentary women 18. The current study found that male middle-distance athletes had lower FVC values of 3.76 ± 0.67 L and FEV1 values of 3.38 ± 0.65 L.

In his 2015 study, Atabek conducted respiratory function tests, handgrip strength tests, and vertical jump measurements on 15.77 ± 0.92-year-old female and 16.15 ± 0.71-year-old male athletes who regularly trained in different sports. Significant differences were found between male and female athletes in all values within the research group. In female and male students, the FVC values were 3.72 ± 0.57 (L) and 5.03 ± 0.75 (L), respectively; and the FEV1 values were 3.10 ± 0.46 (L) and 4.20 ± 0.74 (L), respectively 19. The FVC 3.76 ± 0.67 L and FEV1 3.38 ± 0.65 L values of male middle-distance athletes in the study were found to be similar to the values reported in Atabek’s research.

In a study by Silapabanleng et al. (2020), examining the respiratory function values of short, middle, and long-distance athletes, middle-distance athletes had FEV1 (L) 3.67 ± 0.61 at 800 m distance, FVC (L) 4.06 ± 0.71, and at the 1500 m distance, FEV1 (L) 3.55 ± 0.32 and FVC (L) 3.92 ± 0.55. The study found that male middle-distance athletes had similar results for FEV1 3.38 ± 0.65 L and FVC 3.76 ± 0.67 L. FEV1 (L) is 3.55 ± 0.32 and FVC (L) 3.92 ± 0.55 values have been determined 20. It is thought that this result may be due to the unknown period during which the respiratory parameters of the athletes in Silapabanleng and colleagues’ study were taken. In the study by Rakovac et al.’s (2018), the respiratory function values of athletes engaged in aerobic (mean age 21.98 ± 5.65) and anaerobic sports (average age 20.94 ± 2.53) were found to be FVC (L) 5.10 ± 0.64, FEV1 (L) 4.76 ± 0.54, while anaerobic athletes had FVC (L) 5.16 ± 0.76, FEV1 (L) 4.83 ± 0.56. It was concluded that the maximum oxygen consumption values of the subjects in the aerobic group were significantly higher than those in the anaerobic group 21. In the current research results, it was observed that the FEV1 3.38 ± 0.65 L and FVC 3.76 ± 0.67 values of middle-distance athletes were lower than the values in the literature. This difference is thought to be due to the higher average age and training age.

In their study, Atan et al. (2012) found that among male athletes participating in licensed competitions at the ages of 15-16, the results of respiratory function tests in different branches were as follows: FEV1 (L) was 5.13 ± 1.41 in soccer players, 4.00 ± 1.0 in volleyball players, 4.78 ± 1.21 in basketball players, and 3.36 ± 0.97 in sedentary individuals. FVC (L) values were found to be 5.34 ± 1.34 in soccer players, 4.34 ± 0.97 in volleyball players, 5.21 ± 1.19 in basketball players, and 3.70 ± 0.95 in sedentary individuals 22. The research found that respiratory function was higher in athletes than in non-athletes. The FEV1(L) 3.38 ± 0.65 and FVC (L) 3.76 ± 0.67 values of the 14-18 age group athletes in the current study were found to be low when compared to the results in the literature. This difference is thought to be due to both the athletes’ sports disciplines and the acute nature of the current study.

In the literature, respiratory function tests were performed using a spirometer on male athletes with an average age of 22 ± 4. The study results showed that athletes participating in endurance sports (rowing, canoeing, swimming, long-distance running and marathon, cycling, triathlon, and pentathlon) had higher lung volumes compared to skill, mixed, and power groups, and it was reported that all body composition parameters had an effect on respiratory parameters. In order, technical sports (artistic gymnastics, etc.) FVC (5.8 ± 0.8) and FEV1 (5.1 ± 0.6), power sports (weightlifting, wrestling, etc.). FVC (5.7 ± 1.03) and FEV1 (5.0 ± 0.6) in sports with mixed disciplines (football, basketball, etc.). FVC (5.8 ± 0.04) and FEV1 (5.0 ± 1.1), and in endurance sports (rowing, canoeing, etc.), FVC (6.0 ± 0.9) and FEV1 (5.1 ± 0.7) values were determined 6. Looking at the values of the athletes in this study, which were FEV1 (L) 3.27 ± 0.63 and FVC (L) 4.99 ± 5.99, it is understood that they were low. It is thought that the low research results are due to a lack of training or the possibility of different sports and older training ages.

In the study designed by Vedala et al. (2012) to compare respiratory function tests between athletes and non-athletes, the Lung Function Profile was analyzed, and these values were compared between the study groups. Accordingly, it was determined that the average FVC percentage values of the athletic group were 88.0% ± 12.8, the FEV1 value was 86.8% ± 22.0, the FEV3 value was 86.5% ± 13.7, the PEFR value was 93.0% ± 12.8, and the FEV1 / FVC ratio was 92.1% ± 4.4, which were higher than those of the sedentary group 23.

In their 2017 study, Akhade and Muniyappanavar (2017) compared respiratory function tests of 18-25 year old swimming and marathon players, finding that swimsuits had an FVC (L) of 3.43 ± 0.64 and an FEV (L) of 2.81 ± 0.56. In marathon runners, FVC (L) is 3.10 ± 1.34 and FEV (L) is 2.71 ± 0.82 values were found 24. The values of FEV1 (L) 3.38 ± 0.65 and FVC (L) 3.76 ± 0.67 in the athletes in the current study were observed to be higher than the values in the literature.

Literature indicates that exercise can increase ventilation as tidal volume and respiratory rate increase 25. Similarly, in the study by Shashikala & Jaiswal (2022), which compared respiratory function test values between trained short-distance athletes aged 18-25 and sedentary individuals, the athletes’ FVC values (4.77 ± 0.06) and FEV1 value (3.82 ± 0.04) 6. The results of this study on athletes’ values (FEV1 (L) 3.38 ± 0.65 and FVC (L) 3.76 ± 0.6) were higher.

Recommendations

1. The effects of aerobic exercises applied during the preparation period on athletic performance in middle-distance runners can be examined.

2. It is recommended that studies be conducted comparing the contributions of aerobic and anaerobic training components to athletic performance in the planning of training programs for short- and long-distance runners.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, although the sample size was sufficient for statistical analysis, more middle- distance runners could have been reached if the infrastructure in the region had been supported and strengthened. Reference values on the subject were limited, the results of the study were not compared in detail.

Conclusion

The respiratory function tests (FVC, FEV₁, FEV₁ / FVC) of the middle-distance runners who participated in the study were largely within normal limits, while PEF was observed to be at a slightly low level. Z-scores for FVC, FEV₁, FEV₁/FVC, the Cooper Test, and MaxVO₂ were within normal limits, indicating that the athletes’ performance and respiratory parameters were close to the group average. Low PEF can be explained by measurement technique or individual variations and is not an indicator of respiratory pathology on its own. These results indicate that ventilatory capacity is healthy and sufficient for performance in young athletes. When examining the correlations between athletic performance and respiratory functions, aerobic capacity measurements (Cooper Test and MaxVO₂) showed a high degree of positive correlation with FEV₁, while FVC and FEV₁/FVC showed a moderate degree of positive correlation. Moderate positive correlations were found between strength tests and respiratory parameters, and between flexibility tests and respiratory parameters.

As a result of these findings, it is shown that performance and ventilatory capacity can support each other in middle- distance runners, and that training during the preparation period can have positive effects on respiratory functions. Slightly low PEF values should not be considered an indicator of respiratory pathology on their own, as they may be due to individual variation or measurement technique. In conclusion, the respiratory functions and athletic performance of young middle-distance athletes are at healthy and sufficient levels, and it can be said that performance sports can support lung function.

Tables

Table 1. Analysis results of athletes’ demographic information and subcutaneous adipose tissue measurements

Table 2. Analysis results of athletes’ athletic performance and respiratory function test values

Table 3. Results of Pearson and Spearman correlation analysis of athletes’ athletic performance and PFT values

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed), **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

References

-

Djabbarov A. Methodology of organization of middle running training in athletics. Am J Res Humanit Soc Sci. 2023;17:37-41.

-

Joyner MJ, Coyle EF. Endurance exercise performance: physiology of champions. J Physiol. 2008;586(1):35-44. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143834.

-

Hallam LC, Ducharme JB, Mang ZA, Amorim FT. The role of the anaerobic speed reserve in female middle-distance running. Sci Sports. 2022;37(7):637.e1-8. doi:10.1016/j.scispo.2021.07.006.

-

Nourry C, Deruelle F, Guinhouya C, Baquet G, Fabre C, Bart F, Mucci P. High- intensity intermittent running training improves pulmonary function and alters exercise breathing pattern in children. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2025;94(1):415-23. doi:10.1007/s00421-005-1341-4.

-

Armstrong N, Barker AR. Endurance training and elite young athletes. Med Sport Sci. 2011;56:59-83. doi:10.1159/000320633.

-

Lazovic B, Mazic S, Suzic-Lazic J, et al. Respiratory adaptations in different types of sport. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(12):2269-74.

-

Bompa T. Antrenman Kuramı ve Yöntemi [Training Theory and Methodology]. Ankara: Spor Yayınevi; 2007.

-

Chagnon Y, Allard C, Bouchard C. Red blood cell genetic variation in Olympic endurance athletes. J Sports Sci. 1984;2(2):121-9. doi:10.1080/02640418408729707.

-

Armstrong N, Welsman JR. Aerobic fitness: what are we measuring? Med Sport Sci.2007:50;5-25. doi:10.1159/000101073.

-

Legaz-Arrese A, Munguia-Izquierdo D, Nuviala AN, et al. Average VO2max as a function of running performances on different distances. Sci Sports. 2007;22(1):43-9. doi:10.1016/j.scispo.2006.01.008.

-

Bandyopadhyay A. Validity of Cooper’s 12-minute run test for estimation of maximum oxygen uptake in male university students. Biol Sport. 2015;32(1):59-63. doi:10.5604/20831862.1127283.

-

Rajni P, Deepak M. Comparison of lung function of sedentary vs exercising women. Int J Sports Sci Fitness. 2021;11(2):58–64.

-

Shete AN, Bute SS, Deshmukh PR. A study of VO2max and body fat in female athletes. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):BC01-3. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/10896.5329.

-

Ichikawa D, Miyazawa T, Horiuchi M, Kitama T, Fisher JP, Ogoh S. Relationship between aerobic endurance training and dynamic cerebral blood flow regulation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23(5):e320-9. doi:10.1111/sms.12082.

-

Orhan S, Eskiyecek CG. Effects of basketball training on respiratory functions in female students. Univ J Educ Res. 2018;6(12):2834-40. doi:10.13189/ ujer.2018.061217.

-

Rodríguez-Barbero S, González-Ravé JM, Vanwanseele B, Santos-Garcia DJ, Cruz VM, Gonzales-Mohino F. Effects of 20 weeks of endurance and strength training. Appl Sci. 2025;15(2):903. doi:10.3390/app15020903.

-

Petré H, Tinmark F, Rosdahl H, Psilander N. Effects of different recovery periods following a very intense interval training session on strength and explosive performance in elite female ice hockey players. J Strength Cond Res. 2024;38(7):e383-90. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004782.

-

Kahraman MZ, Okut S, Sari C, Bilici ÖF, Bilici MF. The effect of athletics and football training characteristics on some respiratory parameters in female athletes. Turk J Kinesiol. 2023;9(1):52-8. doi:10.31459/turkjkin.1258836.

-

Atabek HÇ. Farklı spor branşlarında antrenman yapan 15-17 yaş grubu öğrencilerin bazı solunum fonksiyonlarının ve biyomotorik özelliklerinin incelenmesi [Investigation of certain respiratory functions and biomotor characteristics of students aged 15–17 training in different sports disciplines]. Inonu Univ BESBD. 2015;2(1):1-16.

-

Silapabanleng S, Theanthong A, Phangjaem M, Pheungtamon V, Suwondit P. Change in respiratory muscle strength and lung function after different running types. Suranaree J Sci Technol. 2021;28(4):1-7.

-

Rakovac A, Andrić L, Karan V, et al. Evaluation of spirometric parameters and VO2max in athletes and non-athletes. Med Pregl. 2018;71(5-6):157-61. doi:10.2298/MPNS1806157R.

-

Atan T, Akyol P, Çebi M. Comparison of respiratory functions of athletes engaged in different sports branches. Turk J Sport Exerc. 2012;14(3):76-81. doi:10.15314/tjse.98334.

-

Vedala S, Paul N, Mane AB. Differences in pulmonary function between athletes and sedentary persons. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;3(2):118-23. doi:10.5455/njppp.2013.3.109- 114.

-

Akhade VV, Muniyappanavar NS. Evaluation of pulmonary function in sportsmen playing different games. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;7(10):1. doi:10.5455/njppp.2017.7.0516023052017.

-

Cotes JE, Chinn DJ, Miller MR. Lung Function. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Non-Invasive Clinical Researches Mardin Artuklu University (Date: 2025-09-18, No: 214463)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Canan Gülbin Eskiyecek, Mine Gül. The relationship of athletic performance with certain physiological parameters in adolescent middle distance runners. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(1):58-64

Publication History

- Received:

- November 26, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 26, 2025

- Published Online:

- December 30, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026