Evaluation of plasma microRNA expressions in children with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

Plasma microRNAs in children with MASLD

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study investigated the effects of plasma microRNA expression levels on the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis associated with metabolic dysfunction in children.

Methods Twenty-one obese children with MASLD, 23 obese children without MASLD, and 20 age-sex-matched healthy children were enrolled in the study. The plasma levels of five miRNAs (miRNA-21, miRNA-33a, miRNA-33b, miRNA-34a, and miRNA-122a), which are known to be associated with MASLD, were examined in all the subjects. Plasma miRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR in the children. The groups were compared with each other.

Results It was determined that significantly increased levels of miRNA-21 and miRNA-122a, but decreased miRNA-33b and miRNA-34a levels, were observed in both the obese group with MASLD and the obese group without MASLD relative to the control group. No significant differences in those miRNA levels were found between the obese group with MASLD and the obese group without MASLD. However, miRNA-21 and miRNA-122a levels were two-fold higher, and miRNA-33b and miRNA-34a levels were approximately two-fold lower in the obese group with MASLD than in the obese group without MASLD. On the other hand, there were no significant differences in miRNA-33a levels across the study groups.

Conclusion Plasma miRNAs may be involved in the pathogenesis of MASLD in children. More comprehensive and functional research about the role of these molecules is needed in this regard.

Keywords

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the liver and the presence of one of three conditions: obesity/excess weight, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic dysfunction 1. This condition encompasses a wide range of liver damage, from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma 2. Due to the link between obesity and steatotic liver, pediatric MASLD has become a growing global health issue as childhood obesity continues to rise 3,4. Liver biopsy in obese children with MASLD has been the gold standard for diagnosing hepatic steatosisin NAFLD 2. However, due to its high cost and invasive nature, this procedure is not suitable for routine use 5. In this context, new biomarkers are needed to facilitate the diagnosis of MASLD in children.

Over the past decade, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been proposed as potential biomarkers for identifying patients with metabolic disorders. These molecules represent a class of small (19-26 nucleotides), non-coding, highly conserved endogenous RNAs that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level 6. The discovery of their stable circulating structures and their functions in cell physiology has increased interest in their potential use for diagnosing metabolic disorders. Several adult studies in this field have detected significant changes in the expression of a single circulating miRNA or a miRNA panel in patients with metabolic disorders such as obesity and obesity- related diseases, insulin resistance, and diabetes. A similar relationship between serum levels of specific miRNAs and MASLD has also been reported in obese patients. Numerous miRNAs have been investigated in plasma samples from MASLD cases 7.

The present study analyzed the plasma levels of circulating miRNAs in children in terms of weight status and also the absence/presence of MASLD. A panel of fıve miRNAs (miRNA-21, miRNA-33a, miRNA-33b, miRNA-34a, and miRNA- 122a) previously associated with MASLD was studied. These miRNAs were compared between obese children with MASLD, obese children without MASLD, and healthy controls.

Materials and Methods

The study group consisted of 44 obese adolescents followed up at the pediatric gastroenterology clinic for MASLD assessment. Obese adolescents were divided into two groups: the MASLD group (Group 1, n = 21) and the non-MASLD group (Group 2, n = 23). The MASLD group had alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels greater than twice the upper limit of the normal range (males > 50 U/L, females > 44 U/L) and steatotic liver disease detected by ultrasonography (USG). In contrast, the non- MASLD group had normal ALT levels and ultrasonographic liver imaging findings. Obese adolescents having a pre-existing liver condition, with a history of previous/current alcohol use, with genetic, endocrinological, or metabolic diseases capable of causing obesity, or using any medication potentially affecting insulin, glucose, cholesterol, or aminotransferase levels were excluded. Twenty healthy adolescents with normal body mass index (BMI) served as the control group (Group 3).

The heights of all participants in the study were measured using a Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain Limited, Crymych, Dyfed, United Kingdom), and their weights were measured using a calibrated scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula weight (kg)/height (m2). Z-scores for BMI were calculated using reference values for Turkish children 8. BMI Z-scores ≥ 2 according to age and gender were considered an indicator of obesity 9. Body fat was calculated using the bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) method on a Tanita BC 418 device (Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Waist and hip circumference measurements were obtained using a non-stretch tape measure with the patient standing, feet close together (12-15 cm), and arms at their sides. The waist-to-hip ratio was calculated by dividing the waist measurement by the hip measurement. The pubertal status was determined in each case using the Tanner scale.

Fasting venous blood samples were collected from obese adolescents and controls to measure insulin, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglyceride, total cholesterol, ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), and glucose levels. The homeostasis model of assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA- IR) value was calculated using the fasting glucose and fasting insulin values 10.

All participants underwent ultrasonographic examination of the liver to detect fatty liver. The scanning was performed by an experienced radiologist using an Aplio 500 (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) with a linear 4–9-MHz transducer.

miRNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR Analysis

Blood samples were placed in EDTA tubes, and miRNA isolation was performed on the same day. The tubes were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 minutes, and then a total volume of 1000 μl was separated from the top of the plasma obtained using a 200 μl graduated pipette. This 1000 μl plasma was centrifuged again at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes, and 200 μl of the supernatant was collected. The Qiagen miRNeasy serum/ plasma kit (QIAGEN, GmBH, Germany) was used for miRNA isolation. The isolated miRNAs were converted to cDNA using the miScript II RT Kit (QIAGEN, GmBH, Germany). The resulting cDNAs were amplified using the Qiagene miScript® PreAMP PCR kit (QIAGEN, GmBH, Germany) according to the procedures specified in the kit. The Qiagen miScript Primer Assays kit was used for the miRNA-21, miRNA-33a, miRNA-33b, miRNA-34a, and miRNA-122a primers, and the miScript® SYBR® Green PCR kit (QIAGEN, GmBH, Germany) was used for the real-time PCR master mix. Gene expression was evaluated using quantitative real-time PCR (RotorGene Q real-time PCR). Caenorhabditis elegans miRNA cel-miR-39 was used as an endogenous reference gene to normalize miRNA expression levels.

Statistical Analysis

The plasma expressions of miRNA-21, miRNA-33a, miRNA-33b, miRNA-34a, and miRNA-122a were calculated, and the results were compared between groups. To determine the differences in miRNA expression between groups, RT-PCR data were analyzed using the ΔCt module of the Qiagene GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center Portal. The “global CT average of expressed miRNAs” data available at the same analysis center was used for normalization. ΔCt (mean ± SD) values were determined. The relationships between miRNA expression levels between groups were evaluated in terms of 2−ΔCT, and “fold change” values were calculated. Analysis of the results was performed using percentage distribution for qualitative data and median interquartile range (IQR) or mean (standard deviation) values for quantitative data. To compare two groups, Student’s t-test was used for variables showing a normal distribution for independent paired samples, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for those not showing a normal distribution. When there were more than two groups, the ANOVA test was used for variables showing a normal distribution, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for those not showing a normal distribution. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Antalya Training and Research Hospital (Date: 2017-11-30, No:18/05).

Results

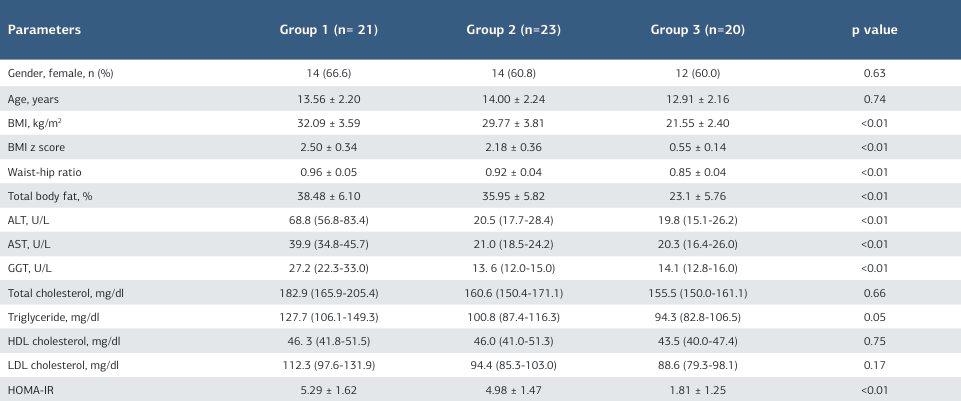

Forty-four obese adolescents and 20 healthy controls participated in the study. Patients’ demographic characteristics, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory parameters are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age and gender between the three groups. The BMI, waist/hip ratio and body fat ratio did not differ significantly between the MASLD group and the non-MASLD group. ALT, AST and GGT concentrations were found to be significantly higher in group 1 than group 2 (p < 0.05).

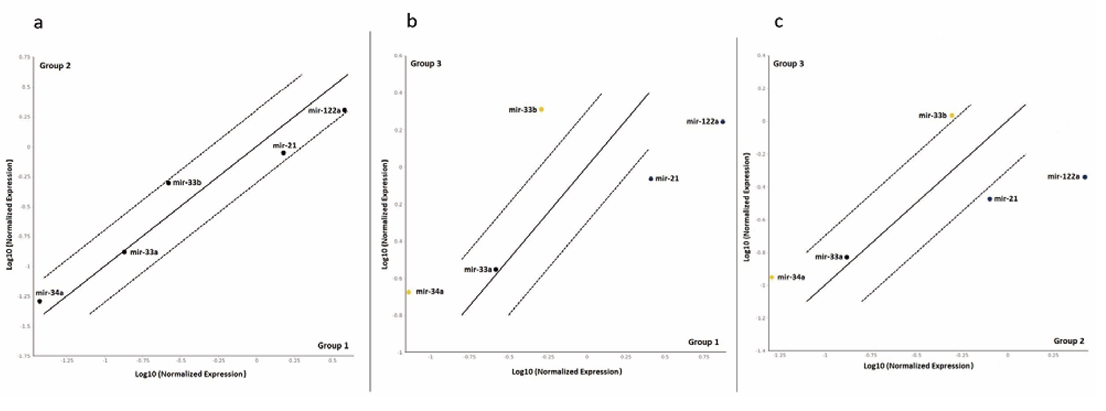

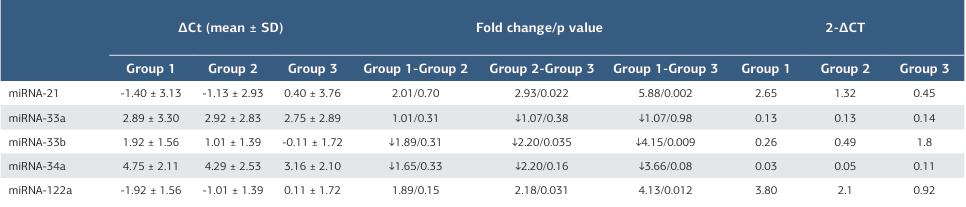

The plasma miRNA ΔCt (mean ± SD) level of the patients and healthy control groups are shown in Table 2. Changes in plasma miRNA expression in the groups are also shown in Figure. In addition, the levels of changes in plasma miRNA 2−ΔCT levels between all the groups are shown in Table 2.

miRNA-21

The mean levels of plasma miRNA-21 2−ΔCT were 2.65 in group 1, 1.32 in group 2, and 0.45 in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference in plasma miRNA-21 levels between group 1 and group 2. However, both group 1 and group 2 had significantly higher miRNA-21 levels compared to the control group.

miRNA-33a

The mean levels of plasma miRNA-33a 2−ΔCT were 0.13 in group 1, 0.13 in group 2, and 0.14 in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference in plasma miRNA-33a levels between group 1 and group 2. In addition, there was no significant difference in plasma miRNA-33a levels between group 1 and group 2 compared to the control group.

miRNA-33b

The mean levels of plasma miRNA-33b 2−ΔCT were 0.26 in group 1, 0.49 in group 2, and 1.08 in the control group. Plasma miRNA- 33b expressions were 1.89-fold lower in group 1 compared to group 2, although this was not statistically significant. These levels decreased 4.15-fold in group 1 compared to the control group, and this was statistically significant. In addition, miRNA- 33b levels were 2.20-fold lower in group 2 than in the control group, and the difference was also statistically significant. miRNA-34a

The mean levels of plasma miRNA-34a 2−ΔCT were 0.03 in group 1, 0.05 in group 2, and 0.11 in control group. Plasma miRNA-34a expressions were 1.65-fold lower in group 1 compared to group 2, but the difference was not statistically significant. miRNA-34a levels decreased 3.66-fold in group 1 compared to the control group and were 2.20-fold lower in group 2 than in the control group and these differences were again without statistical significance.

miRNA-122a

The mean levels of plasma miRNA-122a 2−ΔCTwere 3.80 in group 1, 2.01 in group 2, and 0.92 in control group. Plasma miRNA-122a expressions increased 4.13-fold in group 1 compared to the control group, a statistically significant difference. The levels increased 2.18-fold in group 2 compared to the control group, and this was also statistically significant. Additionally, miRNA-122a levels were 1.89-fold higher in group 1 than in group 2, but this was not statistically significant.

Discussion

This study determined that significantly increased levels of miRNA-21 and miRNA-122a but decreased miRNA-33b and miRNA-34a levels in both the obese group with MASLD and the obese group without MASLD relative to the control group. No significant differences in those miRNA levels between the obese group with MASLD and the obese group without MASLD. However, miRNA-21 and miRNA-122a levels were two-fold higher and miRNA-33b levels two-fold lower in the obese group with MASLD than in the obese group without MASLD.

miRNA-122 constitutes 70% of all miRNAs in the liver and plays a role in various biological processes 11,12. Furthermore, it is known that miRNA-122 regulates metabolic pathways in the liver, including cholesterol biosynthesis 5. Therefore, miRNA-122 has been the focus of previous studies. Thompson and colleagues reported in a study involving children aged 8-18 years that obese children with NAFLD had 12.5 times higher levels of miRNA-122 compared to healthy children 13. However, unlike our study, this study did not include a group of obese children without NAFLD to demonstrate the NAFLD difference. Brandt and colleagues conducted a cohort study involving overweight children from Germany, Italy, and Slovenia 14. Comparison of individuals with and without NAFLD revealed higher miRNA-122 levels in children with NAFLD. However, when the groups were further analyzed, this was observed in German children (where the proportion of NAFLD patients was low) but not in Slovenian children or the Italian group. This may be due to miRNA levels varying according to ethnic origin. In the current study, miRNA-122 levels in the MASLD group were approximately twice as high as in the obese group. However, this was not statistically significant. Furthermore, miRNA levels were also higher in obese children without MASLD compared to the healthy control group.

miRNA-21 is highly expressed in hepatocytes 15. Under pathological conditions, active miRNA-21 levels increase and contribute to molecular changes that trigger liver dysfunction. miRNA-21 plays a role in different stages of NAFLD progression in a cell-specific manner. In our study, we observed an increase in serum miRNA-21 levels in obese patients compared to healthy controls, independent of the presence of MASLD. This increase was approximately sixfold in the MASLD group and approximately threefold in the obese group. Similar to this study, Thomson et al. reported that serum miRNA-21 levels in obese children with NAFLD in a similar age group were approximately 4.89-fold higher than in healthy controls. 13. However, a recent systematic review, which included this study, determined that miRNA levels may increase or decrease depending on the characteristics of the patient populations participating in the studies, their ethnic origins, and the severity of obesity 16. miRNA-33 contributes to the modulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling pathways, as well as the dysregulation of cholesterol synthesis and HDL levels 17. Increased expressions of both miRNA-33a and miRNA-33b have been reported in patients with NAFLD in adult studies 18. In the present study, no difference was observed in levels of miRNA-33a between the groups. Interestingly, however, significantly lower levels of miRNA-33b were detected in both obese (with and without MASLD) groups than in healthy controls, four times lower in individuals with MASLD and twice as low in individuals with obesity only. This diversity, which has not been demonstrated in previous studies, might be due to the different profiles of circulating miRNA in adults and children. miRNAs may therefore have different potentials in the evaluation of diseases in different age groups 19.

miRNA-34a, a central mediator of p53 function, has recently emerged as another miRNA modulated in liver disease 20. Increased miRNA-34a was reported in a mouse model of steatohepatitis 21. miRNA-34a was also up-regulated in serum samples from NAFLD patients 22. In a study involving pediatric obese patients, miRNA-34a levels were reported to be five times higher than in healthy controls 13. Another study in children also found that miRNA-34a was upregulated in the NAFLD group 23. Surprisingly, we determined approximately 3.5-fold lower serum miRNA-34a levels in obese individuals with MASLD compared to the healthy control group, and approximately two-fold lower levels in obese children without MASLD. Some studies have shown that miRNA-34a levels are inversely associated with the severity of liver injury 24. In our study, biopsies were not performed in children with MASLD; we could not completely determine the assessment of liver injury. This may have caused different miRNA-34a levels compared to other studies.

Limitations

First, the study population was relatively small; therefore, we could not provide reliable additional information regarding sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Second, only Turkish subjects were included in this study. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized to other populations with heterogeneous ethnic structures. Third, none of the patients in our study underwent liver biopsy or fibroscopy. Consequently, we were unable to examine the relationship between circulating miRNAs and the degree of fibrosis and inflammation.

Conclusion

New biomarkers and diagnostic tools need to be developed for the identification of MASLD. miRNAs are of interest as biomarkers for the diagnosis and staging of MASLD or as targets for pharmacotherapies to halt or reverse disease progression. The study provides valuable information about miRNA expression in children with MASLD. Increased plasma miRNA-21 and miRNA-122 expression was observed in obese children with MASLD. However, decreased miRNA-33b and miRNA-34a expression was observed. Further studies involving more diverse ethnic groups are needed.

Figures

Figure 1. Changes in plasma miRNA expression in the groups are also shown in Figure (a,b,c). In a, group 2 is compared with group 1; in b, group 3 is compared with group 1; and in c, group 3 is compared with group 2.

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the groups

BMI, body mass index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma glutamyltransferase; HOMA-IR, homeostesis model assessment-estimated insulin resis- tence; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; Values are expressed as median (25th – 75th percentiles) or mean ± SD, as appropriate Calculated for the comparisons between the three groups by using ANOVA for continuous variables. p-value, compared with control, group 1 and group 2

Table 2. Mean plasma miRNA ΔCt levels and plasma miRNA 2−ΔCT (mean) levels between groups and fold change in plasma miRNA 2−ΔCT levels between groups

References

-

Eslam M, Alkhouri N, Vajro P, et al. Defining paediatric metabolic (dysfunction)- associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(10):864-73. doi:10.1016/S2468- 1253(21)00183-7.

-

Vos MB, Abrams SH, Barlow SE, et al. NASPGHAN clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(2):319-34. doi:10.1097/ MPG.0000000000001482.

-

Conjeevaram Selvakumar PK, Kabbany MN, Alkhouri N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: not a small matter. Paediatr Drugs. 2018;20(4):315-29. doi:10.1007/s40272-018-0292-2.

-

Nobili V, Socha P. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: current thinking. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(2):188-92. doi:10.1097/ MPG.0000000000001823.

-

Rinella ME, Tacke F, Sanyal AJ, Anstee QM; participants of the AASLD/EASL Workshop. Report on the AASLD/EASL joint workshop on clinical trial endpoints in NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4):823-33. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.04.019.

-

López-Sánchez GN, Dóminguez-Pérez M, Uribe M, Chávez-Tapia NC, Nuño- Lámbarri N. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and microRNAs expression, how it affects the development and progression of the disease. Ann Hepatol. 2021;21:100212. doi:10.1016/j.aohep.2020.04.012.

-

Liu C. H, Ampuero J, Gil-Gómez A, et al. miRNAs in patients with non- alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2018;69(6):1335-48. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.08.008.

-

Neyzi O, Bundak R, Gökçay G, et al. Reference values for weight, height, head circumference, and body mass index in Turkish children. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2015;7(4):280-93. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.2183.

-

Mercedes de Onis, editor. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for- age: methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.p.139- 78.

-

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner R. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412-9. doi:10.1007/BF00280883.

-

Wang R, Hong J, Cao Y, et al. Elevated circulating microRNA-122 is associated with obesity and insulin resistance in young adults. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(3):291-300. doi:10.1530/EJE-14-0867.

-

Bandiera S, Pfeffer S, Baumert TF, Zeisel MB. miR-122 a key factor and therapeutic target in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(2):448-57. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.004.

-

Thompson MD, Cismowski MJ, Serpico M, Pusateri A, Brigstock DR. Elevation of circulating microRNA levels in obese children compared to healty controls. Clin Obes. 2017;7(4):216-21. doi:10.1111/cob.12192.

-

Brandt S, Roos J, Inzaghi E, et al. Circulating levels of miR-122 and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in pre-pubertal obese children. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(3):175-82. doi:10.1111/ijpo.12261.

-

Androsavich JR, Chau BN, Bhat B, Linsley PS, Walter NG. Disease-linked microRNA-21 exhibitsdrastically reduced mRNA binding and silencing activity in healthy mouse liver. RNA. 2012;18(8):1510-26. doi:10.1261/rna.033308.112.

-

Ortiz-Dosal A, Rodil-García P, Salazar-Olivo LA. Circulating microRNAs in human obesity: a systematic review. Biomarkers. 2019;24(6):499-509. doi:10.1 080/1354750X.2019.1606279.

-

Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Kristo F, Li Y, et al. MicroRNA-33 and the SREBP host genes cooperate to control cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328(5985):1566-9. doi:10.1126/science.1189123.

-

Loyer X, Paradis V, Hénique C, et al. Liver microRNA-21 is overexpressed in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and contributes to the disease in experimental models by inhibiting PPARα expression. Gut. 2016;65(11):1882-94. doi:10.1136/ gutjnl-2014-308883.

-

Corona-Meraz FI, Vázquez-Del Mercado M, Ortega FJ, Ruiz-Quezada SL, Guzmán-Ornelas MO, Navarro-Hernández RE. Ageing influences the relationship of circulating miR-33a and miR- 33b levels with insulin resistance and adiposity. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2019;16(3):244-53. doi:10.1177/1479164118816659.

-

Hermeking H. p53 enters the microRNA world. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(5):414-8. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.028.

-

Pogribny IP, Starlard-Davenport A, Tryndyak VP, et al. Difference in expression of hepatic microRNAs miR-29c, miR-34a, miR-155 and miR-200b is associated with strain-specific susceptibility to dietary nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Lab Invest. 2010;90(10):1437-46. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2010.113.

-

Auguet T, Aragonès G, Berlanga A, et al. miR33a/miR33b* and miR122 as possible contributors to hepatic lipid metabolism in obese women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 24;17(10):1620. doi:10.3390/ ijms17101620.

-

Liu XL, Pan Q, Zhang RN, et al. Disease-specific miR-34a as diagnostic marker of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in a Chinese population. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(44):9844-52. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9844.

-

Kan Changez MI, Mubeen M, Zehra M, et al. Role of microRNA in non- alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a comprehensive review. J Int Med Res. 2023;51(9):3000605231197058. doi:10.1177/03000605231197058.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Antalya Training and Research Hospital (Date: 2017-11-30, No:18/05)

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Arzu Aras, Alperhan Cebi, Hamdi Cihan Emeksiz, Ishak Abdurrahman Isik, Senol Citli, Ulas Emre Akbulut. Evaluation of plasma microRNA expressions in children with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(1):65-69

Publication History

- Received:

- November 17, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 11, 2025

- Published Online:

- December 22, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026