Serum endocan reflects endothelial activation in cutaneous vasculitis

Serum endocan in LCV patients

Authors

Abstract

Aim To assess whether serum endocan—an index of endothelial activation—is elevated in biopsy-confirmed cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV), its correlations with CRP/ESR/NLR/SII, and its diagnostic performance by ROC analysis.

Methods In this cross-sectional case–control study, we enrolled 37 biopsy-confirmed LCV patients and 37 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. ELISA measured serum endocan. CRP, ESR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) were recorded. Diagnostic performance was assessed by ROC analysis. A prespecified multivariable linear regression adjusted for comorbidities and demographics (CKD, CVD, diabetes, inflammatory diseases, thyroid disorders, age, and sex).

Results Serum endocan levels were higher in LCV than in controls (p = 0.027). Endocan did not correlate with CRP, ESR, NLR, or SII (all p > 0.05). After multivariable adjustment, vasculitis status remained independently associated with higher endocan (small/borderline effect; adjusted R² = 0.042), and a sensitivity backward stepwise model confirmed a significant association (b = 3299.22 pg/mL; 95% CI 93.56–6504.87; p = 0.044). ROC analysis showed moderate discrimination (AUC = 0.70); at a prespecified cut-off of > 1077 pg/mL, sensitivity was 49% and specificity 78%.

Conclusion Serum endocan is elevated in LCV and appears to reflect localized endothelial activation rather than systemic inflammatory burden. Although its standalone diagnostic power is limited, endocan may serve as a complementary biomarker when interpreted alongside clinical and histopathological findings.

Keywords

Introduction

Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a small-vessel inflammatory disorder that primarily involves postcapillary venules of the skin and represents one of the most common histopathologic patterns of cutaneous vasculitis in dermatologic practice 1.

Clinically, it typically presents with crops of 1–3 mm palpable purpura on the lower extremities, often accentuated at pressure/ trauma sites 2. According to the Dermatologic Addendum to the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference, cutaneous small- vessel vasculitis—although frequently skin-limited—may also appear as a skin-dominant form of systemic vasculitis, warranting careful clinical evaluation 1,2. Histopathology shows neutrophilic infiltration with leukocytoclasia and fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls 3,4.

An underlying trigger or systemic association is identified in roughly half of cases (infections, inflammatory diseases, drugs, malignancies), whereas the remainder are single-organ cutaneous LCV or idiopathic forms 1,5. Pathophysiologically, LCV is an immune-complex–mediated hypersensitivity vasculitis in which endothelial activation—amplified by cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β—plays a central role 1,2,6. Endocan (endothelial cell–specific molecule-1, ESM1) is a circulating dermatan-sulfate proteoglycan secreted by activated endothelial cells; its expression is induced by inflammatory and angiogenic stimuli (e.g., VEGF), making it a practical serum marker of endothelial dysfunction compared with membrane- bound adhesion molecules 7,8,9,10. To our knowledge, no prior study has specifically evaluated serum endocan in biopsy- confirmed cutaneous LCV. We therefore measured serum endocan in patients with LCV and examined its relationship with systemic inflammatory indices (SII, NLR, ESR, CRP).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study including 37 consecutive adults with biopsy-confirmed LCV who presented to the Dermatology Clinic of the University of Health Sciences, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, between June 2024 and December 2024, and 37 healthy controls from the same institution, frequency- matched by age and sex. Inclusion criteria for patients were age 18–80 years and a clinical–histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous LCV. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy/lactation and any specific systemic vasculitis (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, IgA vasculitis) or another dermatologic disease. For controls, exclusion criteria were any history of systemic disease, active infection, pregnancy/lactation, current immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory therapy, or any dermatologic disease. Participants were not excluded based on systemic comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, malignancy); these were recorded and later adjusted for in the analyses.

A standardized history and full dermatologic examination were performed. Presumed triggers before lesion onset (infections, inflammatory diseases, drug exposure, neoplasms, genetic disorders, recent surgery) were recorded. Elementary lesions (palpable/macular purpura, petechiae, urticarial or annular/ targetoid papules-plaques, vesicles, bullae, pustules, livedo racemosa, retiform purpura, subcutaneous nodules, alopecia, digital necrosis, ulcers) were documented.

After ≥ 8 h fasting, venous blood was drawn in the morning while seated. For serum, 5 mL was collected into BD Vacutainer SST II Advance tubes with clot activator/gel (LOT 4024601; Becton Dickinson, Plymouth, UK), allowed to clot for 30 min, and centrifuged at 1,500 g for 10 min. Serum aliquots were stored at −80 °C; multiple freeze–thaw cycles were avoided. Routine tests included hemoglobin, white blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). The systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) was calculated as platelet × neutrophil/lymphocyte, and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was calculated as neutrophil/lymphocyte.

Serum endocan (ESM1) concentrations (pg/mL) were measured using a commercial ELISA (Human ESM1 ELISA Kit, Cat. No. E-EL-H1557; Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations were interpolated from a standard curve (analytical range 15.63–1000 pg/mL). Samples above the upper limit of quantification were re- assayed after appropriate serial dilutions; final values were multiplied by the dilution factor.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in SPSS v15.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of continuous variables was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and Q–Q plots. Between-group comparisons used Student’s t-test for normally distributed data or Mann– Whitney U for non-normal data; categorical variables used χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Correlations were examined with Pearson or Spearman as appropriate. Diagnostic performance of endocan was evaluated by ROC analysis (AUC with 95% CI), and sensitivity/specificity were reported for the a priori cut-off > 1077 pg/mL.

To identify independent associations with endocan, we fitted a multivariable linear regression including prespecified covariates—chronic kidney disease (CKD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), inflammatory diseases, thyroid disorders, vasculitis status (patient vs. control), age, and sex. Binary predictors were coded as 0/1, and age was continuous. Model assumptions (linearity, independence, residual normality, and homoscedasticity via White’s test) and multicollinearity (VIF) were checked. Because diagnostics indicated departures from normality and homoscedasticity, inferences were interpreted cautiously, and the final results were checked in a backward-stepwise sensitivity analysis. Missing data were minimal and handled by complete-case analysis. All tests were two-sided with α = 0.05. Using G*Power 3.1, a two- tailed independent-samples t-test (α = 0.05) indicated ~85% post hoc power to detect Cohen’s d≈0.70 with 37 LCV and 37 controls; sensitivity analysis showed the minimum detectable effect for 80% power was d≈0.66 (a priori sizing was not feasible given the rarity of LCV, ~45 / million).

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ankara Etlik City Hospital (Date: 2024-06-12, No: 588).

Results

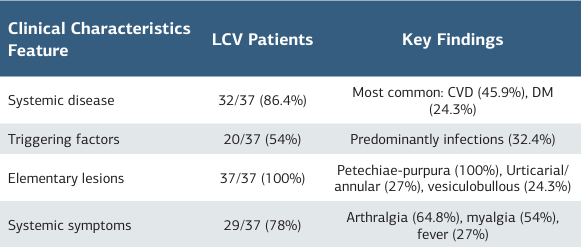

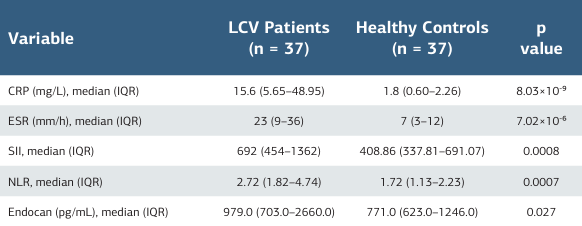

The study included 37 patients with LCV (27 female, 10 male) and 37 healthy controls (27 female, 10 male). Sex distributions were identical; mean age was similar between groups (patients: 57.32 ± 15.53 years; controls: 49.70 ± 11.10; p > 0.05). The median disease duration was 6 days (IQR 3–6). No control participant had a concomitant systemic disease; the summarized clinicalcharacteristics of the patients are presented in table 1. Patients showed higher CRP, ESR, SII, NLR, and endocan values compared with controls (all p < 0.05). Further laboratory details are provided in table 2, and detailed clinical characteristics are presented in supplementary table 1. Serum endocan did not correlate with CRP (r = 0.159, p = .348), ESR (r = 0.027, p = .877), NLR (r = 0.087, p = .610), or SII (r = 0.072, p = .671), nor with routine hematologic/biochemical parameters.

Among LCV patients, nine had pre-existing CKD and ten experienced transient creatinine elevation during the disease course; endocan levels did not differ by CKD, DM, or CVD status (each p > 0.05). In addition, no significant correlation was observed between serum endocan and creatinine (Spearman’s ρ = 0.24, p = 0.153, n = 37). Fecal occult blood was positive in six patients, yet endoscopic/colonoscopic evaluations showed no vasculitis. Newly developed renal involvement was not associated with endocan (p = 0.442). In the overall cohort (patients + controls), a prespecified multivariable linear regression adjusting for CKD, CVD, DM, inflammatory diseases, thyroid disorders, age, and sex identified vasculitis status (LCV vs. control) as the only variable independently associated with higher endocan (borderline in the complete model, p = 0.057). In a sensitivity backward stepwise analysis, vasculitis was the sole retained predictor and remained associated with a small but statistically significant increase in endocan (b = 3299.22, 95% CI [93.56, 6504.87], p = 0.044; F(1.72) = 4.21, R2 = 0.055, adjusted R2 = 0.042). Model diagnostics indicated heteroscedasticity (White’s test, p < 0.001) and non-normal residuals (Shapiro– Wilk test, p < 0.001). ROC analysis demonstrated moderate discrimination for LCV (AUC = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60–0.81; p < 0.001), with 49% sensitivity and 78% specificity at a cut-off value of 1077 pg/mL.

Discussion

We found that serum endocan levels were higher in LCV than in matched controls and remained independently associated with vasculitis after adjustment for comorbidities. Consistent with the absence of correlations between endocan and CRP, ESR, NLR, or SII, this pattern suggests that endocan primarily reflects local endothelial activation rather than global systemic inflammation. This interpretation is supported by histopathology showing early endothelial activation in LCV lesions—up-regulation of E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1, particularly in early biopsies—and the association of E-selectin with neutrophilic infiltration. Moreover, experimental data indicate that endocan expression is induced by inflammatory and angiogenic stimuli such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and VEGF 7. In line with this mechanism, immune-complex deposition in postcapillary venules with complement activation and C5b-9 formation provides a mechanistic link to endothelial injury and leukocyte recruitment 2. The basal expression of adhesion molecules in non-inflamed dermal vessels further supports a cutaneous immune-surveillance system that may operate independently of overt systemic inflammation 6. These data support a model in which immune-complex deposition and complement activation trigger local endothelial activation; circulating endocan appears to capture this endothelial signal even when systemic inflammatory markers remain low.

Elevated endocan has been reported across several inflammatory/dermatologic conditions—including Behçet disease (BD), rosacea, psoriasis, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA)—and has been associated with subclinical vascular dysfunction (e.g., increased carotid intima–media thickness) 8,11,12,13,14,15. Studies in systemic autoimmune diseases (Systemic sclerosis (SSc), RA, BD) similarly describe higher endocan without consistent correlation to CRP/ESR; in SSc, levels are higher in the presence of vascular complications (pulmonary hypertension, digital ulcers), supporting endocan as a marker of endothelial dysfunction rather than general inflammation 16. By contrast, no difference was noted in lichen planus 17. In psoriasis, serum/lesional endocan levels tend to increase and may correlate with disease severity and subclinical atherosclerosis, although treatment effects are inconsistent across studies 10,15,18,19. Our data—elevated endocan in LCV but poor correlation with systemic indices—fit within this broader pattern.

Meta-analytic data indicate that the association between CKD and circulating endocan is more evident in plasma than in serum; studies using serum often fail to show differences versus controls 20. Thus, the effect of CKD may be limited in the serum matrix; however, given the small CKD subgroup, these findings should be interpreted as the absence of evidence rather than evidence of absence.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It is a single-center, cross- sectional analysis with a modest sample size reflecting the rarity of cutaneous LCV, so temporal dynamics and prognostic implications could not be assessed. Some statistical assumptions were not fully satisfied; therefore, the regression results should be interpreted cautiously and ideally validated in larger, independent cohorts. Nevertheless, strengths include biopsy confirmation, age- and sex-matching, and prespecified multivariable adjustment for key comorbidities.

Conclusion

Serum endocan was elevated in biopsy-confirmed cutaneous LCV and, after adjustment for CKD, CVD, diabetes, thyroid, and inflammatory diseases, age, and sex, remained independently associated with vasculitis. The absence of correlations with CRP, ESR, NLR, and SII suggests that endocan primarily reflects local endothelial activation rather than overall systemic inflammatory burden. On ROC analysis, endocan provided moderate discrimination (AUC = 0.70) with high specificity (78%) but modest sensitivity (49%), indicating value as a complementary—not stand-alone—biomarker alongside clinical and histopathologic assessment. These findings appeared robust to common comorbidities, including CKD, in this serum-based cohort. Larger, multicenter, longitudinal studies are needed to validate cut-offs, define temporal dynamics, and clarify prognostic utility.

Tables

Table 1. Summary of the main clinical and laboratory charac- teristics of LCV patients

Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus

Table 2. Laboratory comparisons between cutaneous LCV patients and healthy controls

Abbreviations: Data are presented as median (interquartile range, IQR). P-values were obtained using the Mann–Whitney U test. CRP = C-reactive protein; SII = systemic immune-inflammation index; NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; LCV = leukocytoclastic vasculitis

References

-

Fraticelli P, Benfaremo D, Gabrielli A. Diagnosis and management of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16(4):831-41. doi:10.1007/ s11739-021-02688-x.

-

Cassisa A, Cima L. Cutaneous vasculitis: insights into pathogenesis and histopathological features. Pathologica. 2024;116(2):119-33. doi:10.32074/1591- 951X-985.

-

Micheletti RG, Werth VP. Small vessel vasculitis of the skin. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(1):233-44. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40136-2_21.

-

Shavit E, Alavi A, Sibbald RG. Vasculitis—what do we have to know? A review of literature. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2018;17(4):218-26. doi:10.1177/1534734618804982.

-

DeHoratius DM. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Postgrad Med. 2023;135(Suppl 1):44-51. doi:10.1080/00325481.2022.2159207.

-

Yap BJM, Lai-Foenander AS, Goh BH, et al. Unraveling the immunopathogenesis and genetic variants in vasculitis toward development of personalized medicine. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:732369. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.732369.

-

Liu S, Bai T, Feng J. Endocan, a novel glycoprotein with multiple biological activities, may play important roles in neurological diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024;16:1438367. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2024.1438367.

-

Balta I, Balta S, Koryurek OM, et al. Serum endocan levels as a marker of disease activity in patients with Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):291-6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.013.

-

Bessa J, Albino-Teixeira A, Reina-Couto M, Sousa T. Endocan: a novel biomarker for risk stratification, prognosis and therapeutic monitoring in human cardiovascular and renal diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;509:310-35. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.07.041.

-

Balta I, Balta S, Demirkol S, et al. Elevated serum levels of endocan in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: correlations with cardiovascular risk and activity of disease. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(5):1066-70. doi:10.1111/bjd.12525.

-

Kılıc S, Mermutlu SI, Şehitoğlu H, Ekinci A. Elevated serum endocan levels in patients with rosacea: a new therapeutic target? Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66(5):520-4. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_401_21.

-

Yılmaz Y, Durmuş RB, Saraçoğlu B, et al. The assessment of serum endocan levels in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arch Rheumatol. 2017;33(2):168-73. doi:10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2018.6528.

-

Kul A, Ateş O, Alkan Melikoğlu M, et al. Endocan measurement for active Behçet disease. Arch Rheumatol. 2017;32(3):197-202. doi:10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2017.6072.

-

Nassef EM, Elabd HA, El Nagger BMMA, et al. Serum endocan levels and subclinical atherosclerosis in Behçet’s syndrome. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:6653-9. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S373863.

-

Hassan WA, Behiry EG, Abdelshafy S, Salem T, Baraka EA. Assessment of endocan serum level in patients with Behçet disease: relation to disease activity and carotid intima media thickness. Egypt J Immunol. 2020;27(1):129-39.

-

Mahgoub MY, Fouda AI, Elshambaky AY, Elgazzar WB, Shalaby SA. Validity of endocan as a biomarker in systemic sclerosis: relation to pathogenesis and disease activity. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil. 2020;47(1):23. doi:10.1186/s43166- 020-00025-2.

-

Ozlu E, Karadag AS, Toprak AE, et al. Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors, haematological and biochemical parameters, and serum endocan levels in patients with lichen planus. Dermatology. 2016;232(4):438-43. doi:10.1159/000447587.

-

Sigurdardottir G, Ekman AK, Verma D, Enerbäck C. Decreased systemic levels of endocan-1 and CXCL16 in psoriasis are restored following narrowband UVB treatment. Dermatology. 2018;234(5-6):173-9. doi:10.1159/000491819.

-

Erek Toprak A, Ozlu E, Uzuncakmak TK, et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, serum endocan, and nesfatin-1 levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris undergoing phototherapy treatment. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:1232-7. doi:10.12659/MSM.898240.

-

Khalaji A, Behnoush AH, Mohtasham Kia Y, Alehossein P, Bahiraie P. High circulating endocan in chronic kidney disease? A systematic review and meta- analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(8):e0289710. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0289710.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Health Sciences, Ankara Etlik City Hospital (Date: 2024-06-12, No: 588)

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all participants and healthcare staff who contributed to the conduct of this study.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Gamze Taş Aygar, Mine Büşra Bozkürk, Ramazan Burak Sivri, Gökberk Uyar, Hatice Ataş, Canan Topçuoğlu, Selda Pelin Kartal. Serum endocan reflects endothelial activation in cutaneous vasculitis. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(1):7578

Publication History

- Received:

- November 22, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 22, 2025

- Published Online:

- December 29, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026