The results of intraoperative diluted hydrogen peroxide in empyema surgery

Empyema surgery

Authors

Abstract

Aim Empyema is a dense, sticky inflammation of the pleural cavity. Many treatment approaches have been reported so far. A 3% hydrogen peroxide solution administered orally does not cause serious toxicity. We aim to share the effects of intraoperative intrapleural diluted 3% hydrogen peroxide on the surgical outcomes of patients who underwent decortication.

Materials and Methods Of patients who underwent decortication due to empyema, those with or without intraoperative, intrapleural administration of diluted 3% H2O2 were randomly selected and divided into two groups. A total of 36 patient cases were analyzed.

Results In terms of duration, the results of Group 1 were more significant compared to Group 2. Regarding postoperative drainage catheter removal, the results for Group 1 were more significant than Group 2. In terms of the mean hospital stay, the results of Group 1 were statistically more significant compared to Group 2 (p<0.05).

Discussion In patients with empyema with pleural thickening and loculations, the use of intraoperative intrapleural diluted 3% hydrogen peroxide shortens the mean operation time, time to removal of the drainage catheter, and hospital stay. It also has a positive effect on the recovery period.

Keywords

Introduction

Empyema is a dense, sticky inflammation of the pleural cavity. The most common cause is the infection of parapneumonic effusions with infective agents in cases of bacterial or viral pneumonia [1]. The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) classified parapneumonic effusions based on the anatomy, bacteriology, and chemistry of the fluid and divided into 4 categories (1, 2, 3, 4) [2]. If left untreated, empyema causes morbidity and has a mortality rate of more than 10% [3, 4]. There are no specific symptoms in empyema cases. Laboratory examinations show elevated leukocytes, sedimentation, and CRP levels as well as anemia. Radiological examinations include posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs, lateral decubitus radiographs, US, CT, and MRI [1].

The main principles in empyema treatment are the control of infection and sepsis with appropriate antibiotic therapy, drainage of purulent fluid, prevention of resistant or recurrent disease by obliterating the empyema cavity, and reexpansion of the underlying lung tissue. Many treatment approaches have been reported so far. Thoracotomy-decortication is a surgical method applied in the presence of multiple loculations unresponsive to fibrinolytic therapy that cannot be drained by tube thoracostomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). However, the main problems with the decortication procedure are prolonged operation time, pulmonary parenchyma damage, prolonged air leaks, extended hospitalization, and the development of reloculations and infections [5].

Hydrogen peroxide is a natural bactericide used by leukocytes [6]. It is used in medicine for wound irrigation and the sterilization of ophthalmic and endoscopic instruments [7]. A 3% hydrogen peroxide solution administered orally does not cause serious toxicity [8]. In our study, we aimed to share the effects of intraoperative intrapleural diluted 3% hydrogen peroxide on the surgical outcomes of patients who underwent decortication.

Statistical Analysis

In statistical analysis, continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were stated as numbers and percentages. Results were evaluated using Mann-Whitney U tests. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Materials and Methods

Patients who underwent decortication due to empyema, were randomly selected and divided into two groups based on whether they received intraoperative, intrapleural, and diluted 3% H2O2. A total of 36 patients were analyzed. Group 1 (G1; n=21) consisted of patients who received H2O2, while Group 2 (G2; n=15) included patients who did not H2O2 The study investigated the age, gender, symptoms, localization of the disease, radiological findings, diagnosis and treatment, complications, and mortality and morbidity of the patients. Obtained results were compared between the two groups.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by Firat University Ethics Comitee (Date: 2021-09-23, No: 2021/10-35).

Results

The most common symptoms in both groups were fever, cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath. All patients were diagnosed by chest X-ray and mostly by computed tomography (CT) of the thorax.

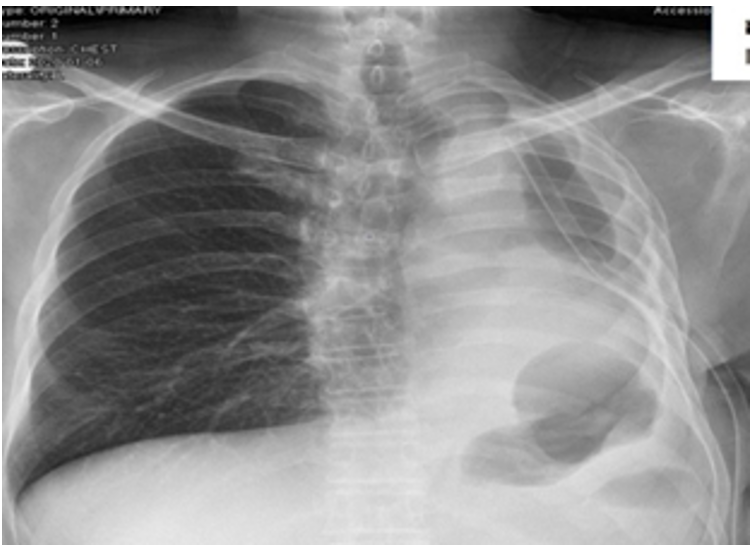

All patients had air trapping and, fluids could not be obtained by thoracentesis or with catheter/tube thoracostomy (Figure 1, 2). Consequently, all patients underwent posterolateral thoracotomy.

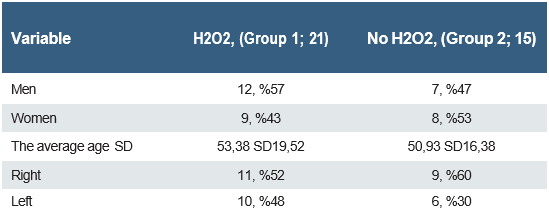

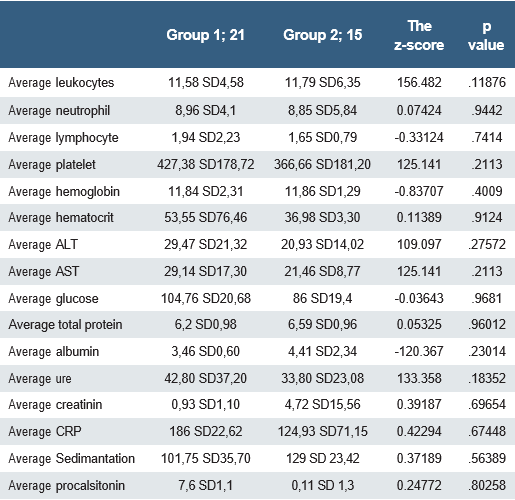

The mean age of Group 1 patients was 53.38 ± 19.52 years. Twelve (57%) of the patients were male, while nine (43%) were female. The disease was located on the right side in 11 (52%) patients and on the left side in 10 (48%) patients. The mean age of Group 2 patients was 50.93 ± 16.38 years. Seven (47%) of the patients were male while 8 (53%) were female. The disease was located on the right side in 9 patients (60%) and left side in 6 patients (30%) (Table 1). The obtained fluids were exudative in both groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of blood values (p>0.05) (Table 2).

ARB results were negative in both groups. Enterobacter cloacae was seen in one patient and Escherichia coli in one patient in Group 1, while Klebsellia pneumonia growth was identified in only one patient in Group 2.

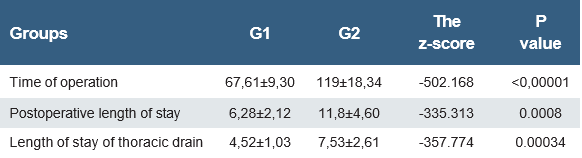

The mean operation duration was 67.61 ± 9.30 minutes in Group 1, while it was 119 ± 18.34 in Group 2 patients. The results of Group 1 were significantly better compared to Group 2 (p<0.05) (Table 3).

The mean postoperative drainage catheter termination was

4.52 ± 1.03 days in Group 1 patients, while it was 7.53 ± 2.61 days in Group 2 patients. The results for Group 1 were significantly better than Group 2 (p<0.05) (Table 3).

The mean hospital stay was 6.28 ± 2.12 days in Group 1, while it was 11.8 ± 4.60 days in Group 2. The results for Group 1 were significantly better compared to Group 2 (p<0.05) (Table 3).

The pathological diagnosis was pleuritis in 12 patients, mesothelioma in 6, and granulomatous infection in 3 in Group 1, while in Group 2, there were 9 patients with pleuritis, 3 with mesothelioma, and 3 with granulomatous infection.

Metronidazole and cephalosporins were given as routine postoperative treatment. This treatment was sufficient for all of the patients in Group 1. However, 3rd generation single or combined antibiotics were needed in 6 patients in Group 2.

No serious complications were observed in Group 1 patients following the operation. In contrast, purulent discharge in the chest drain necessitated, long-term antibiotic washing and long-term 3rd generation antibiotics in 3 (20%) patients in Group 2. One patient (6.6%) was admitted to the intensive care unit due to high fever, respiratory distress, tachycardia, and hypotension and subsequently died.

Discussion

Causes of empyema include lobar pneumonia, lung abscess, bronchiectasis, previous thoracic, cardiac, or esophageal surgery, septic pulmonary embolism, trauma, mediastinitis, abdominal infections, spontaneous pneumothorax, improper thoracentesis, malignancy, esophageal perforation, and sepsis [9]. If left untreated, it can cause morbidity as well as mortality, with a rate of more than 10% [3, 4]. In our study, nonspecific pleuritis was found in 12 patients in Group 1, mesothelioma in 6, and granulomatous infection in 3, while nonspecific pleuritis was seen in 9 patients in Group 2, mesothelioma in 3, and granulomatous infection in 3. Since our study included postoperative data, our postoperative morbidity rate was 20% and the mortality rate was 6.6% in Group 2 patients.

There are no specific symptoms of empyema. Symptoms that are similar to those of pneumonia, include shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, cough, purulent sputum, fever, chills, and weight loss. Radiological examinations include posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs, lateral decubitus radiographs, ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT) of the thorax. Thoracic tomography is particularly important due to its contribution to determining the appropriate treatment method [1, 10]. In our study, the most common symptoms in both groups were fever, cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath. It was observed that all patients were diagnosed with computed tomography of the thorax, while chest X-ray was less preferred. Parameters such as pH, protein, glucose, and lactic dehydrogenase are checked in the pleural fluid taken from patients with empyema. Demonstrating that the fluid characteristic is exudate is important for the diagnosis [11]. In addition, ADA level, cell count, Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic cultures, cytological examination, and ARB should be checked in these materials and the etiology should be investigated. In most patients, many microorganisms together cause empyema, with Gram-positive aerobes being the most common among these [9, 12, 13]. In our study, while the characteristics of the fluids were exudate in both groups, there was no statistical difference between the groups in terms of blood values. While ARB results were negative in both groups, Enterobacter cloacae was found in one patient in Group 1, and Escherichia coli in one patient, while Klebsellia pneumonia growth was seen in only 1 patient in Group 2.

Empyema due to parapneumonic effusions includes three periods called exudative, fibrinopurulent, and organization. Its classification was made by the American College of Chest Physicians in 2000 and it was divided into 4 groups: 1, 2, 3, and 4 [2]. The patients included in our study were fibrinopurulent, mostly in the organization stage, and were classified as 3 and 4.

The general principles of empyema treatment are the control of infection and sepsis with appropriate antibiotic therapy, drainage of purulent fluid, prevention of resistant or recurrent disease by obliterating the empyema cavity, and reexpansion of the underlying lung tissue. The main methods are observation, thoracentesis, tube thoracostomy, fibrinolytic therapy, thoracoscopic interventions, decortication, and open drainage methods. In category 1 parapneumonic effusions, specific and effective antibiotic therapy is usually sufficient and close observation is required. Although pleural drainage with tube thoracostomy still plays a major role in the treatment of empyema, it is not sufficient in 36-65% of patients. If clinical and radiological improvement is not observed within 24 hours with tube thoracostomy, it indicates that either pleural drainage is insufficient or the appropriate antibiotics are not being used for the causative microorganism.

Reasons for inadequate pleural drainage include the incorrect positioning of the thoracic tube, loculations, or thickening of the visceral pleura, which prevents lung expansion. Fibrinolytic therapy is used for difficult-to-drain fluids due to their viscosity and their multiple loculations with tube thoracostomy. During this process, drainage is facilitated by breaking down loculated areas using streptokinase, urokinase, and tissue plasminogen activators. Side effects include anaphylaxis, hemorrhage, and pulmonary edema [13, 14, 15, 16]. In our study, all patients had air trapping, and fluids could not be obtained by thoracentesis, nor were results obtained with catheter/tube thoracostomy and fibrinolytic therapy. Therefore, posterolateral thoracotomy was performed in all patients.

Decortication with thoracotomy involves removing all the fibrous tissue from the visceral and parietal pleura, completely clearing the purulent fluid and debris, and allowing the underlying lung to expand. The decortication procedure, which has a high success rate, is associated with 1.3-6.6% mortality rate. The most important issues in this procedure include difficulty releasing the trapped lung, the length of the operation, the parenchymal leaks that occur during the separation of the fibrous layer from the visceral pleura of the lung, the prolonged use of thoracic tubes due to leaks, the formation of re-loculations, and extended hospitalization [17, 18] . In our study, no serious complications were observed in Group 1 patients after the operation. However, purulent discharge in the thoracic drain was seen in three patients in Group 2, necessitating long-term antibiotic washing and long-term use of 3rd generation antibiotics, and one patient experienced a high fever. Additionally, one patient in Group 2 was admitted to the intensive care unit due to high fever, respiratory distress, tachycardia, and hypotension and subsequently died.

Hydrogen peroxide is a natural bactericide used by leukocytes. It acts by three main mechanisms: corrosive damage, oxygen gas generation, and lipid peroxidation. Concentrated hydrogen peroxide solutions are toxic and may cause local tissue damage upon exposure. However, even if a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution is taken orally, it does not cause serious toxicity [1]. Oral ingestion of hydrogen peroxide at concentrations greater than 10% results in local damage, and ingestion of concentrations greater than 35% can result in death. Hyrogen peroxide is also used in medicine for wound irrigation and the sterilization of ophthalmic and endoscopic instruments. It has been used in many general, plastic, and orthopedic surgeries to remove dead tissue and control infection [6, 7, 8]. It has also been used in thoracic surgery to control operation site infections and remove skin damage. However, it has not been used intraoperatively in patients with empyema to eliminate the resistance of the fibrous layer that develops on the lung, to remove loculations, to facilitate decortication, and to prevent leaks. In our study, the use of intraoperative hydrogen peroxide facilitated the separation of fibrotic tissue developing on the visceral pleura from the lung and chest wall, thus preventing possible complications such as massive air leaks and bleeding. Very successful results were obtained in patients who underwent thoracotomy-decortication with the use of intraoperative intrapleural diluted 3% hydrogen peroxide. The results for Group 1 patients were found to be significantly better compared to Group 2 in terms of average operation time, duration of drainage, and hospital stay.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, including only 36 patients, which may limit the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Second, although patients were described as “randomly selected,” the randomization method was not strictly controlled, and therefore, selection bias may have occurred. Third, the study was conducted in a single center, which may limit the applicability of the results to different institutions or surgical teams. Fourth, the severity of empyema, inflammatory markers, and radiological staging were not compared between groups in detail, which may have influenced perioperative outcomes. Additionally, the lack of long-term follow-up data prevented evaluation of late complications such as recurrence, fibrothorax, and pulmonary function recovery. Finally, although intrapleural diluted hydrogen peroxide was used at a standardized concentration, the optimal dosage and safety profile require further prospective studies with larger patient populations.

Conclusion

In patients with empyema characterized by pleural thickening and loculations, the use of intraoperative intrapleural diluted 3% hydrogen peroxide shortens the mean operation time, duration of drainage, and hospital stay, and has a positive effect on the recovery.

Figures

Figure 1. Chest X-ray of a patient with empyema

Figure 2. Computed tomography of the thorax of a patient with empyema

Tables

Table 1. Demographic distribution of patients who underwent thoracotomy for empyema

Table 2. Laboratory values of patients who underwent thoracotomy for empyema

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate aminotransferase, CRP: C-reactive protein, LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase, Av: Average

Table 3. Results of patients using and not using H2O2

References

-

Singh S, Singh SK, Tentu AK. Management of parapneumonic effusion and empyema. J Assoc Chest Physicians. 2019;7:51-8.

-

Shen KR, Bribriesco A, Crabtree T, et al. American Association for Thoracic Surgery consensus guidelines for the management of empyema. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2017;153(6):129-46.

-

Schweigert M, Solymosi N, Dubecz A, et al. Surgery for parapneumonic pleural empyema-What influence does the rising prevalence of multimorbidity and advanced age has on the current outcome? Surgeon. 2016;14(2):69-75.

-

Kanai E, Matsu N. Management of empyema: A comprehensive review. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2020;2:3.

-

Bedawi EO, Hassan M, Rahman NM. Recent. Developments in the management of pleural infection: A comprehensive review. Clin Respir J 2018;12:2309-20.

-

Papafragkou S, Gasparyan A, Batista R, Scott P. Treatment of portal venous gas embolism with hyperbaric oxygen after accidental ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: a case report and review of the literatüre. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(1):21- 3.

-

Sansone J, Vidal N, Bigliardi R, Voitzuk A, Greco V, Costa K. Unintentional ingestion of 60% hydrogen peroxide by a six-year-old child. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42(2):197-9.

-

Watt BE, Proudfoot AT, Vale JA. Hydrogen peroxide poisoning, Toxicol Rev. 2004;23(1):51-7.

-

Foroulis CN, Kleontas A, Karatzopoulos A, et al. Early reoperation performed for the management of complications in patients undergoing general thoracic surgical procedures. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(1):21-31.

-

Trejo-Gabriel-Galan, JM, Macarron-Vicente JL, Lazaro L, Rodriguez- Pascual L, Calvo I. Intercostal neuropathy and pain due to pleuritis. Pain Med. 2013;14(5):769-70.

-

Light RW. A New Classification of Parapneumonic Effusions and Empyema. Chest. 1995;108(2):299-301.

-

Tsujimoto N, Saraya T, Light RW, et al. A Simple Method for Differentiating Complicated Parapneumonic Effusion/Empyema from Parapneumonic Effusion Using the Split Pleura Sign and the Amount of Pleural Effusion on Thoracic CT. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6): 130-141.

-

Girotti PNC, Tschann P, Stefano PD, Möschel M, Hübl N, Königsrainer I. Retrospective case–control study on the outcomes of early minimally invasive pleural lavage for pleural empyema in oncology patients. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:2710-18.

-

Ozkan S, Yazici U, Aydin E, Celik A, Akin A, Karaoglanoglu N. Risk Factors in Development of Postoperative Empyema. J Clin Anal Med. 2014; 5(1):19-24.

-

Delanote I, Budts W, De Leyn P, Dooms C. Large bronchopleural fistula after surgical resection: secret to success. J Thorac Oncol. 2016; 11(2): 268-69.

-

Burt BM, Shrager JB. The prevention and management of air leaks following pulmonary resection. Thorac Surg Clin. 2015; 25(4): 411-19.

-

Pohnán R, Blažková S, Hytych V, et al. Treatment of hemothorax in the era of the minimaly invasive surgery. Mil. Med. Sci. Lett. 2019;88(4):180-87.

-

Federici S, Bédat B, Hayau J, et al. Outcome of parapneumonic empyema managed surgically or by fibrinolysis: A multicenter study. J Thorac Dis 2021;13(11):6381-63.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Firat University (Date: 2021-09-23, No: 2021/10-35)

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The corresponding author has committed to share the de-identified data with qualified researchers after confirmation of the necessary ethical or institutional approvals. Requests for data access should be directed to bmp.eqco@gmail.com

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Siyami Aydin, Muharrem Cakmak. The results of intraoperative diluted hydrogen peroxide in empyema surgery. Ann Clin Anal Med 2025;16(11):772-776

Publication History

- Received:

- May 15, 2024

- Accepted:

- September 24, 2024

- Published Online:

- April 17, 2025

- Printed:

- November 1, 2025