Case report of saccharomyces cerevisiae infection: root-cause analysis and remediation study

Case report of saccharomyces cerevisiae infection

Authors

Abstract

Introduction Saccharomyces cerevisiae, used as yeast in producing foods such as beer, wine, and bread, is present in human microbiota and the natural environment. However, the increase in infection cases in recent years is remarkable.

Case Presentation This report presents a urinary tract infection caused by S. cerevisiae in a patient with no history of probiotic use. The root-cause analysis of the infection and the improvement study were developed accordingly. In this context, it was found that the healthcare personnel who inserted a urinary catheter into the patient during hospitalisation in the intensive care unit fermented wine at home and checked the wine every morning. However, it could not be confirmed whether the isolated strain was the same as the strain in the urine culture since molecular-level studies could not be performed. Failure to comply with infection control measures during the treatment and care of at-risk individuals can lead to S. cerevisiae infection, an opportunistic pathogen.

Conclusion By identifying the source of infection through root-cause analysis and carrying out improvement activities to the institution’s characteristics, the healthcare professional’s awareness can be raised, compliance with infection control measures can be increased, and behavioural change can be achieved.

Keywords

Introduction

S. cerevisiae, known as yeast, used in producing foods such as beer, wine, and bread, is present in human microbiota and the environment 1. It is generally non-pathogenic 1,2. The use of S. boulardii, a subtype of S. cerevisiae, as a probiotic in treating diarrhoea due to antibiotic use in recent years has increased infection 1. Risk factors such as intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalisation, high-risk patient groups (such as leukaemia), elderly, premature children, corticosteroid, antibiotic, and probiotic use, central venous catheters (CVC), immunosuppression, hand hygiene non-compliance are predisposing factors for invasive Saccharomyces infections 2. In recent years, Saccharomyces infections have increased due to increased immunosuppressive patients and developments in molecular diagnostic methods. Cases of fungemia, prosthetic valve endocarditis, peritonitis, cholecystitis, pneumonia, empyema, liver abscesses, vaginitis, and urinary tract infection (UTI) indistinguishable from Candida albicans have been reported in the literature 1,3,4. This report presents a case of urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by S. cerevisiae in a patient with no history of probiotic use, the root-cause analysis, and the improvement study developed with the FOCUS-PDCA model. This case report has been prepared in accordance with the CARE case report guide.

Case Presentation

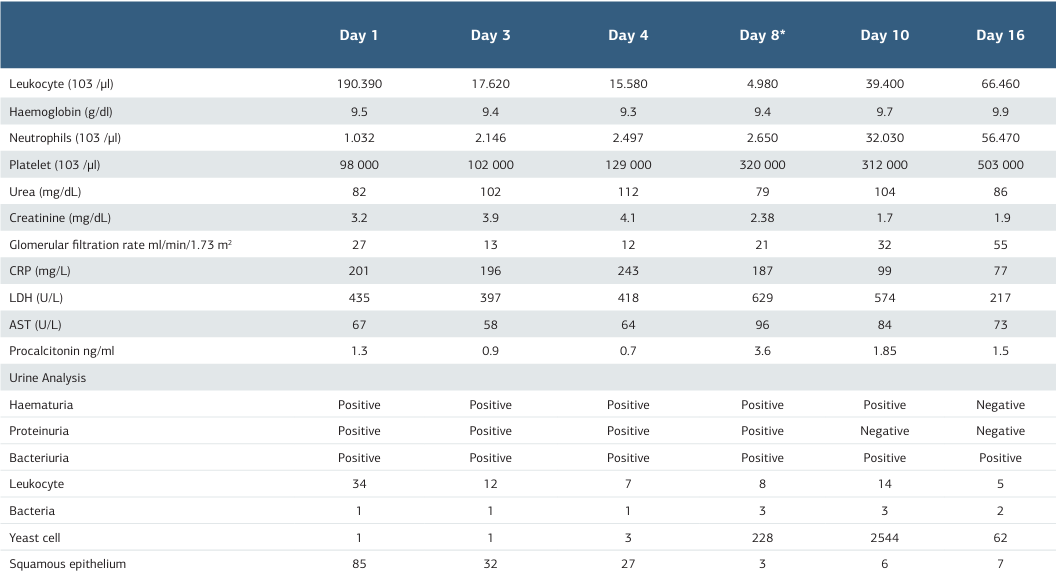

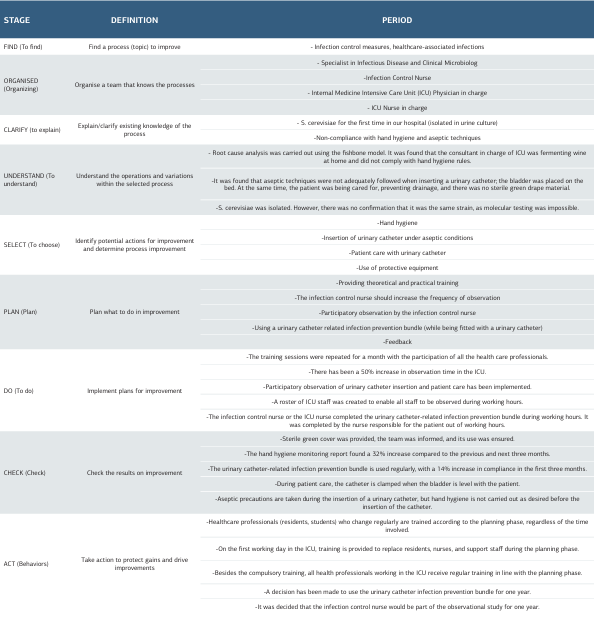

A 62-year-old woman with diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and right heart failure was admitted to the emergency department with complaints of chills, fever, malaise, abdominal pain, and dyspnoea. The patient did not smoke or drink alcohol. Blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, heart rate 88/min, temperature 39.4o C, SPO2 88. Physical examination revealed (++) pretibial oedema, oliguria, dysuria, partial rales based on lung auscultation, and orthopneic dyspnoea. No suspicious findings related to infection were found on chest radiography. Laboratory examination revealed proteinuria, haematuria, bacteriuria, pancytopenia, neutropenia, leucocytosis, increased C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin levels. The patient was hospitalised in the infectious diseases ward, and treatment and follow-up were started. Vancomycin 2x1, meropenem 3x1, and enoxaparin sodium 1x0.4 IU were started empirically in addition to the drugs used due to chronic diseases. Filgrastim 1x48 IU (5 days) was added to the treatment with the recommendation of haematology for neutropenia. No growth was detected in blood and urine cultures taken on the first day of hospitalisation in the infectious diseases ward. On the third day of hospitalisation, renal function started to deteriorate. The dose of vancomycin and meropenem was changed to 1x1 g according to creatinine clearance. The patient was transferred to the Internal Medicine Intensive Care Unit (ICU) on the fourth day. In the ICU, a CVC was placed in the right femoral vein, and haemodialysis with ultrafiltration was performed for 4 hours for three consecutive days. A urinary catheter (UIC) was also inserted. On admission to the ICU, the patient had sub-febrile fever, hypotension, tachycardia, and macroscopic haematuria. No growth was detected in blood and urine cultures taken consecutively on the first day of ICU admission. On the eighth day of hospitalisation (4th day in the ICU), urine microscopy revealed an intense amount of yeast cells. Simultaneously, urine culture was incubated in Yeast Extract Glucose Chloramphenicol Agar FIL-IDF medium at 37o C for 24 hours. At the end of incubation, yeasts were detected in the colonies grown on the medium, and the isolates were identified as S. cerevisiae by the BD PhoenixTM Yeast ID system. According to the results of urine microscopy, the patient’s urinary catheter (UC) was excluded, and fluconazole 1x100 mg (5 days) was added to the treatment. No growth was detected in the blood culture. Renal functions and vital signs started to improve. After the 10th day of hospitalisation, CRP and procalcitonin values began to improve, but leukocyte and neutrophil levels were found to increase continuously. Bone marrow biopsy was performed, and amyloidosis and multiple myeloma were considered. Myeloid young cells were predominantly detected in the peripheral smear. On the 12th day of hospitalisation, the patient was diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia and transferred to the haematology clinic. No growth was detected in the urine culture sent for the control on the 16th day of hospitalisation. The patient was discharged on the 44th day of hospitalisation. The patient’s culture results are shown in Table 1, and laboratory findings are shown in Table 2. The infection control physician and nurse performed a root cause analysis due to the growth in urine culture. Accordingly, it was determined that the patient did not use beer, wine, and probiotics and did not ferment bread at home, but a staff member working in the intensive care unit made wine at home. It was determined that the UIC was implanted by the staff fermenting wine during the patient’s ICU admission. S. cerevisiae was detected in the wine sample. However, it could not be confirmed whether the isolated strain was the same as the strain in the urine culture since it was impossible to perform molecular-level studies. With the decision of the infection control committee, improvement work was initiated with the FOCUS-PDCA model to prevent healthcare-associated infections and to increase the awareness of the multidisciplinary team (Table 3). In this context, all personnel working in the ICU were given repeated training on hand hygiene, use of protective equipment, insertion of UIC under aseptic conditions, and care of patients with UIC. The observation period of the infection control nurse was increased by 50%, and participant observation was provided as a role model. Missing personal protective equipment was provided. The ICU team was motivated to use the bundle to prevent UIC-associated infections. As a result, hand hygiene compliance increased by 32% in the first three months. The use of the UIC-associated infection prevention bundle increased by 14% and continued to be used for one year. Patient care with UIC was started to be performed appropriately. Compliance with aseptic techniques during UIC insertion was achieved, but hand hygiene compliance during catheter insertion still needed to be increased.

Discussion

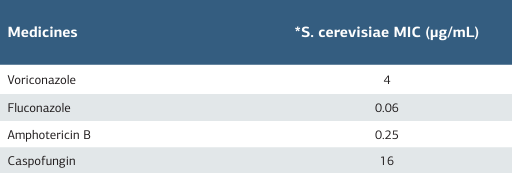

S. cerevisiae can be colonised in the hospital when hand hygiene is inadequate 5 and cleaning and disinfection procedures are not done properly 1. Live S. cerevisiae cells can be airborne up to one meter and remain on all living/non-living surfaces for approximately two hours 6,7. Cassone et al. (2003) reported that three patients developed fungemia in the ICU due to insufficient attention to infection procedures, while probiotic treatment was administered to other patients 6. Elkhihal et al. (2015) reported that they separated S. cerevisiae in the urine culture of a 40-year-old type 2 diabetic patient without probiotic use due to digestive system translocation 8. Intense yeast was observed in the urine sample four days after UIC insertion and S. cerevisiae was isolated in urine culture. Our patient, who had no history of probiotic use, did not use probiotics to treat other patients in the ICU. As a result of the root-cause analysis, it was determined that the personnel who put UIC on the patient fermented wine at home and checked the wine every morning. The fact that S. cerevisiae can remain on bare hands even after hand washing 7 suggests that the most probable cause was insufficient hand hygiene and compliance with aseptic techniques during UIC insertion. One of the responsibilities of the infection control physician and nurse assigned to the infection control committee within the scope of the Infection Control Regulation of inpatient treatment institutions is to determine the cause of infection and carry out studies to solve and improve the problem. In this case, the possible causes of infection were discussed using the fishbone model, and improvement work was carried out with the FOCUS- PDCA model to solve the problem. In this context, the awareness of healthcare personnel and compliance with infection control measures were increased and the healthcareassociated infection rate decreased. Accordingly, no infection caused by S. cerevisiae has been encountered in our hospital for the last three years. Studies have reported that S. cerevisiae is sensitive to antifungal agents such as voriconazole, fluconazole, amphotericin B, caspofungin, micafungin 1,2,4. It is seen that many cases in the literature were treated with fluconazole (5- 15 days) 2,5,6,8. However, cases are treated with caspofungin 3, amphotericin B, and a combination of micafungin and fluconazole 1. In S. cerevisiae infection, fluconazole used for 5-15 days may be useful alone in medical treatment. In addition to medical treatment, an important strategy is removing the invasive device associated with the infection and terminating probiotics. In cases in the literature, it is reported that invasive devices such as CVC and UC are removed immediately after the development of infection 1,3,4,6. It is even suggested that success can be achieved only by removing the invasive device 6. Similar to the treatment and care strategies in the literature, our patient’s UC was released, fluconazole treatment was applied, and success was achieved. In studies, age, high- risk patients (such as leukaemia, renal failure, diabetes), chemotherapy, radiotherapy, use of immunosuppressive agents, antibiotics, probiotics, ICU hospitalisation, CVC, UC, total parenteral nutrition, failure of healthcare personnel to provide proper hand hygiene, failure to comply with procedures for infection control measures have been reported as risk factors for S. cerevisiae infection 1,2,3,4,5. In our case, in addition to chronic diseases such as diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and heart failure, the patient’s diagnosis of leukaemia, the use of broad- spectrum antibiotics, the continuation of treatment and care in the ICU, and the use of UIC constitute risk factors for infection. However, transporting the microorganism to our hospital with contaminated hands and failing to ensure proper hand hygiene and aseptic techniques during UIC insertion constitute important preventable risk factors for infection.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as a single-case report, the findings cannot be generalised to broader patient populations or different clinical settings. Second, although the possible source of S. cerevisiae contamination was identified through a root-cause analysis, molecular typing could not be performed; therefore, the genetic similarity between the isolate detected in the patient’s urine culture and the isolate obtained from the wine sample could not be confirmed. Third, environmental sampling in the intensive care unit was not conducted, which limited the ability to comprehensively assess potential environmental reservoirs.

Conclusion

Non-compliance with infection control measures during treating and caring for individuals at risk of infection may cause S. cerevisiae infection, an opportunistic pathogen. By determining the source of infection through root-cause analysis and carrying out improvement activities by the institution’s characteristics, the healthcare professional’s awareness can be raised, compliance with infection control measures can be increased, and behavioural change can be achieved. In this direction, S. cerevisiae infection can be prevented, and the healthcare-associated infection rate can be reduced.

Tables

Table 1. Urine culture results

*4 days after urinary catheter insertion

Table 2. Laboratory findings of the patient during follow-up and treatment

*4 days after urinary catheter insertion, CRP: C-reactive protein, LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase, AST: Aspartate aminotransfer

Table 3. Improvement study according to the FOCUS-PDCA model

References

-

Fadhel M, Patel S, Liu E, Levitt M, Asif A. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia in a critically ill patient with acute cholangitis and long-term probiotic use. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2018;12(23):3-5. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2018.11.003.

-

Appel-da-Silva MC, Narvaez GA, Perez LRR, Drehmer L, Lewgoy J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii fungemia following probiotic treatment. Medical Mycology Case Reports. 2017;18:15-7. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2017.07.007.

-

Gün E, Özdemir H, Besli Çelik D, Botan E, Kendirli T. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia due to an unexpected source in the pediatric intensive care unit. Turk J Pediatr. 2022;64:138-41. doi:10.24953/turkjped.2020.1668.

-

Atıcı S, Soysal A, Karadeniz Cerit K, et al. Catheter-related Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia following saccharomyces boulardii probiotic treatment: in a child in intensive care unit and review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2017;15:33-5. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2017.02.002.

-

Pinto G, Lima L, Pedra T, Assumpção A, Morgado S, Mascarenhas L. Bloodstream infection by Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a COVID-19 patient receiving probiotic supplementation in the ICU in Brazil. Access Microbioll. 2021;3(8):000250. doi:10.1099/acmi.0.000250.

-

Cassone M, Serra P, Mondello F, et al. Outbreak of saccharomyces cerevisiae subtype boulardii fungemia in patients neighbouring those treated with a probiotic preparation of the organism. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(11):5340-3. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.11.5340–5343.2003.

-

Hennequin C, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, Jobert A, et al. Possible role of catheters in saccharomyces boulardii fungemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19(1):16-20. doi:10.1007/s100960050003.

-

Elkhihal B, Elhalimi M, Ghfir B, Mostachi A, Lyagoubi M, Aoufi S. Infection urinaire à saccharomyces cerevisiae: levure émergente [Urinary infection by Saccharomyces cerevisiae: emerging yeast]? J Mycol Med. 2015;25(4):303-5. doi:10.1016/j.mycmed.2015.09.004.

Declarations

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kayseri University (Date: 2019-06-28, No: 16)

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the internal medicine intensive care team, mycologist and infection control team members for supporting the study.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Serife Cetin, Ilhami Celik. Case report of saccharomyces cerevisiae infection: Root-cause analysis and remediation study. Ann Clin Anal Med 2026;17(1):79-83

Publication History

- Received:

- February 27, 2024

- Accepted:

- April 2, 2024

- Published Online:

- April 19, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026